Movies We Like

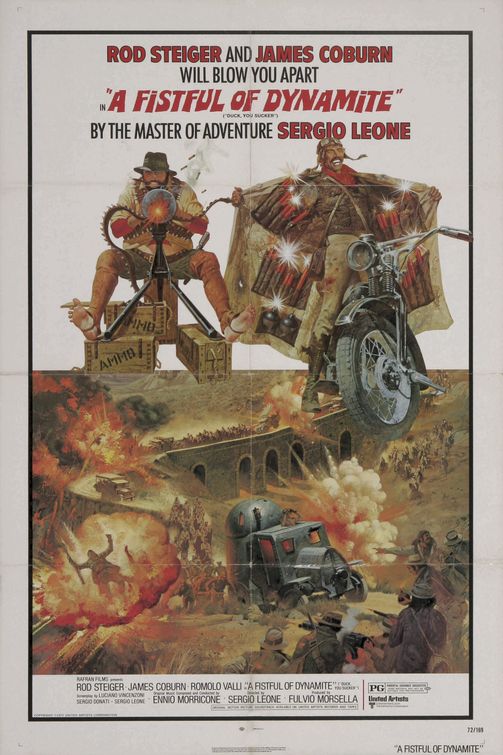

Duck, You Sucker (AKA A Fistful of Dynamite)

Dir: Sergio Leone, 1971. Starring: Rod Steiger, James Coburn, Romolo Valli. Westerns.

If Once Upon a Time in the West was Sergio Leone’s North by Northwest or Rear Window, then Duck, You Sucker (AKA A Fistful of Dynamite) was his Vertigo. It was a misunderstood film in its day; fans were startled by the director breaking from his formula and actually trying to say something. But like Hitchcock, what he had to say also didn’t satisfy what audiences wanted to hear, and the pace didn’t give them the thrills they were used to. With Duck, You Sucker, Leone was working on a potentially bigger canvas than Once Upon a Time in the West. Working with his biggest budget yet meant that Leone did have to concede his casting choices to the studio. Rod Steiger and James Coburn were hardly Leone’s first choices to play the leads, but United Artists considered both big stars while Jason Robards wasn’t bankable enough and Clint Eastwood was no longer available.

Throughout Leone’s Eastwood “Man with No Name” trilogy, each film was made back-to-back-to-back (A Fistful of Dollars, For a Few Dollars More and The Good, the Bad & the Ugly) and each got more progressively ambitious in both scope and ambition as their popularity grew. Finally, the director peaked with his follow-up, Once Upon a Time in the West, an accumulation of all the ideas he had been building towards and both the ultimate post-modern western and one of the true film masterpieces of the 1960s. He finally took a break (three years) before returning to the screen with the eccentric Duck, You Sucker (afterwards he would take an even longer break, not being a credited director for 11 years). In some territories the film was titled Once Upon a time in the Revolution or A Fistful of Dynamite but it would not fully fit with his first four flicks (we all tend to ignore his unrecognizable debut The Colossus Of Rhodes in ’61). Everything about this new film felt slightly tweaked. Its tones moved from comic to dramatic to sentimental to tragic to cartoony much less gracefully than in his past work. The setting moved south to Mexico and the period moved up a couple decades. Where Once Upon a Time in the West had a deliberate pace, the strands perfectly came together and justified their speed, while at almost 160 minutes Duck, You Sucker sometimes just feels long and, worse, indulgent. But luckily that indulgence and the hint of a director slightly lost in his creation proves to be both fascinating and entertaining. And just as westerns had been reinvented in the ‘60s, the ‘70s saw another seismic shift where movies as diverse as Duck, You Sucker, El Topo, The Missouri Breaks, and, finally, Heaven’s Gate would help to kill the genre for a generation.

Mexico in 1913 was ripe for revolution; when we first meet Juan Miranda (Steiger), he’s pissing on an anthill (a rebuttal reference to the opening of Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch). He’s a seemingly illiterate country bandit; along with his giant pack of sons he robs from the rich and besides taking their money and possessions, he gets off on humiliating them, the same way his low social status makes him feel humiliated. He meets an Irish dynamite expert, John Mallory (Coburn), as he tools around the dusty Mexican back streets on a motorcycle. Juan sees a cash cow in John (literally, in one of the film’s funniest moments). The two make a shaky partnership. Juan wants to blow things up for his outlaw gains, while John is actually an Irish Republican soldier on the run from his home country, bringing his TNT expertise to the revolution in Mexico. And in Juan he sees a potential new revolutionary. John constantly leads Juan astray; instead of robbing banks Juan finds himself freeing political prisoners, making himself a hero without even knowing it. Slowly Juan and John form a bond as well, but friendship haunts John.

Villa and Zapata may be close by, but the revolution on film is actually led by Doctor Villega (Romolo Valli, who is often associated with his work in Luchino Visconti’s films, including The Leopard). He and John have disagreements over how a revolution should be fought. Leone makes a point of showing that while the intellectuals talk, it’s actually the peasants (Juan and family) that do the hard work and take the biggest risks. No one realizes just how haunted John is by his Irish past. In dreamy flashbacks that grow longer each time we return to them, the film’s best moments are when John remembers back to his life in the lushly green Ireland (Leone actually shot the scenes on location in Dublin). He and a pal shared a passion for the IRA as well as for the same woman (they even have a threesome). But it’s never clear which one John loved more, all leading to a big, sad betrayal and John’s expulsion. Now, out of his gloom with Juan, he finds there is more to revolution—loyalty and friendship are just as important. And, of course, Juan finds new meaning in his crime and even almost comes to believe in his new political persona.

Like all of Leone’s films, the real star of the show is his collaborator, the prolific composer Ennio Morricone. In Duck, You Sucker, even more than in his four previous Leone films, the stunning score substitutes for dialogue. There are long passages of tight close-ups on Steiger and Coburn where they say nothing and let Morricone do the talking for them. The two American stars often go in and out of their foreign accents, but it’s still both their best film and performances of the decade. Similar to Eli Wallach’s Mexican Tuco in The Good, the Bad & the Ugly, Steiger finds a lot of ham to chew on in the role. Throughout his career, even in his peak years in the ‘60s, with his string of startling performances in The Pawnbroker, Doctor Zhivago, The Loved One, and In the Heat of the Night, he always seemed to be walking that thin light between high-art and over-emoting. But in Duck, You Sucker, like the other films, he is so grounded in reality and so totally committed to the role that even when it reeks of an Actor’s Studio act-off, he’s still utterly compelling. Coburn has bigger shoes to fill; he may not have the skills of Robards or the stoic coolness of Eastwood or Charles Bronson, but he does have a smile and a sly humor that they lack. Steiger and Coburn make for an odd couple screen team, one laid back while the other is acting up a storm. In the end, it helps make the film so much more unusual, and that’s a good thing.

Duck, You Sucker, with its strong political slant, is more than just another western; while its nighttime train ambush is reminiscent of Richard Brooks’s The Professionals, it feels closer to Queimada (Burn!) by Gillo Pontecorvo in spirit. A dressed-up period piece with something to say about contemporary social issues, Leone may have intended it to be apolitical but the student upheavals and revolutionary talk on the streets of Europe are said to have influenced him, even if cynically. There are also references to WWII, with allusions to the Holocaust and Italian fascism, while also featuring a Nazi tank driver, making this Leone’s kitchen sink movie (he threw everything in).

Again, a Leone or Spaghetti Western first-timer should start with Once Upon a Time in the West and then do the three Eastwood flicks, but that wouldn’t satisfy the hunger of a true cinephile, so Duck, You Sucker is a perfect dessert. It’s not as clean as the previous films, almost sloppy, and with less quotable dialogue, but that’s only in comparison. On its own it’s still incredibly rewarding; it’s beautifully shot by Giuseppe Ruzzolini (who also shot Burn!), well acted, and deals with a fascinating subject matter. Like Hitchcock, no matter the rank in Leone’s (small by comparison) canon, everything is worth seeing and incredibly influential. What, at the time, might have been written off as lower-tier Leone has found new fans and new life; perhaps it’s still in need of a Vertigo-like rediscovery by the masses and then people will realize that Leone was truly one of the titans of international cinema.

Throughout Leone’s Eastwood “Man with No Name” trilogy, each film was made back-to-back-to-back (A Fistful of Dollars, For a Few Dollars More and The Good, the Bad & the Ugly) and each got more progressively ambitious in both scope and ambition as their popularity grew. Finally, the director peaked with his follow-up, Once Upon a Time in the West, an accumulation of all the ideas he had been building towards and both the ultimate post-modern western and one of the true film masterpieces of the 1960s. He finally took a break (three years) before returning to the screen with the eccentric Duck, You Sucker (afterwards he would take an even longer break, not being a credited director for 11 years). In some territories the film was titled Once Upon a time in the Revolution or A Fistful of Dynamite but it would not fully fit with his first four flicks (we all tend to ignore his unrecognizable debut The Colossus Of Rhodes in ’61). Everything about this new film felt slightly tweaked. Its tones moved from comic to dramatic to sentimental to tragic to cartoony much less gracefully than in his past work. The setting moved south to Mexico and the period moved up a couple decades. Where Once Upon a Time in the West had a deliberate pace, the strands perfectly came together and justified their speed, while at almost 160 minutes Duck, You Sucker sometimes just feels long and, worse, indulgent. But luckily that indulgence and the hint of a director slightly lost in his creation proves to be both fascinating and entertaining. And just as westerns had been reinvented in the ‘60s, the ‘70s saw another seismic shift where movies as diverse as Duck, You Sucker, El Topo, The Missouri Breaks, and, finally, Heaven’s Gate would help to kill the genre for a generation.

Mexico in 1913 was ripe for revolution; when we first meet Juan Miranda (Steiger), he’s pissing on an anthill (a rebuttal reference to the opening of Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch). He’s a seemingly illiterate country bandit; along with his giant pack of sons he robs from the rich and besides taking their money and possessions, he gets off on humiliating them, the same way his low social status makes him feel humiliated. He meets an Irish dynamite expert, John Mallory (Coburn), as he tools around the dusty Mexican back streets on a motorcycle. Juan sees a cash cow in John (literally, in one of the film’s funniest moments). The two make a shaky partnership. Juan wants to blow things up for his outlaw gains, while John is actually an Irish Republican soldier on the run from his home country, bringing his TNT expertise to the revolution in Mexico. And in Juan he sees a potential new revolutionary. John constantly leads Juan astray; instead of robbing banks Juan finds himself freeing political prisoners, making himself a hero without even knowing it. Slowly Juan and John form a bond as well, but friendship haunts John.

Villa and Zapata may be close by, but the revolution on film is actually led by Doctor Villega (Romolo Valli, who is often associated with his work in Luchino Visconti’s films, including The Leopard). He and John have disagreements over how a revolution should be fought. Leone makes a point of showing that while the intellectuals talk, it’s actually the peasants (Juan and family) that do the hard work and take the biggest risks. No one realizes just how haunted John is by his Irish past. In dreamy flashbacks that grow longer each time we return to them, the film’s best moments are when John remembers back to his life in the lushly green Ireland (Leone actually shot the scenes on location in Dublin). He and a pal shared a passion for the IRA as well as for the same woman (they even have a threesome). But it’s never clear which one John loved more, all leading to a big, sad betrayal and John’s expulsion. Now, out of his gloom with Juan, he finds there is more to revolution—loyalty and friendship are just as important. And, of course, Juan finds new meaning in his crime and even almost comes to believe in his new political persona.

Like all of Leone’s films, the real star of the show is his collaborator, the prolific composer Ennio Morricone. In Duck, You Sucker, even more than in his four previous Leone films, the stunning score substitutes for dialogue. There are long passages of tight close-ups on Steiger and Coburn where they say nothing and let Morricone do the talking for them. The two American stars often go in and out of their foreign accents, but it’s still both their best film and performances of the decade. Similar to Eli Wallach’s Mexican Tuco in The Good, the Bad & the Ugly, Steiger finds a lot of ham to chew on in the role. Throughout his career, even in his peak years in the ‘60s, with his string of startling performances in The Pawnbroker, Doctor Zhivago, The Loved One, and In the Heat of the Night, he always seemed to be walking that thin light between high-art and over-emoting. But in Duck, You Sucker, like the other films, he is so grounded in reality and so totally committed to the role that even when it reeks of an Actor’s Studio act-off, he’s still utterly compelling. Coburn has bigger shoes to fill; he may not have the skills of Robards or the stoic coolness of Eastwood or Charles Bronson, but he does have a smile and a sly humor that they lack. Steiger and Coburn make for an odd couple screen team, one laid back while the other is acting up a storm. In the end, it helps make the film so much more unusual, and that’s a good thing.

Duck, You Sucker, with its strong political slant, is more than just another western; while its nighttime train ambush is reminiscent of Richard Brooks’s The Professionals, it feels closer to Queimada (Burn!) by Gillo Pontecorvo in spirit. A dressed-up period piece with something to say about contemporary social issues, Leone may have intended it to be apolitical but the student upheavals and revolutionary talk on the streets of Europe are said to have influenced him, even if cynically. There are also references to WWII, with allusions to the Holocaust and Italian fascism, while also featuring a Nazi tank driver, making this Leone’s kitchen sink movie (he threw everything in).

Again, a Leone or Spaghetti Western first-timer should start with Once Upon a Time in the West and then do the three Eastwood flicks, but that wouldn’t satisfy the hunger of a true cinephile, so Duck, You Sucker is a perfect dessert. It’s not as clean as the previous films, almost sloppy, and with less quotable dialogue, but that’s only in comparison. On its own it’s still incredibly rewarding; it’s beautifully shot by Giuseppe Ruzzolini (who also shot Burn!), well acted, and deals with a fascinating subject matter. Like Hitchcock, no matter the rank in Leone’s (small by comparison) canon, everything is worth seeing and incredibly influential. What, at the time, might have been written off as lower-tier Leone has found new fans and new life; perhaps it’s still in need of a Vertigo-like rediscovery by the masses and then people will realize that Leone was truly one of the titans of international cinema.

Posted by:

Sean Sweeney

Dec 5, 2011 6:01pm