Movies We Like

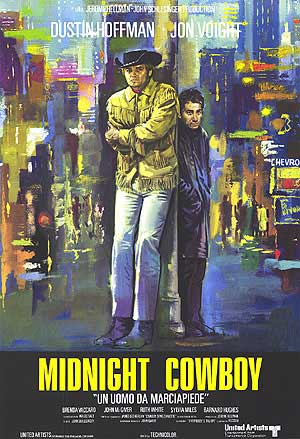

Midnight Cowboy

Dir: John Schlesinger, 1969. Starring: Jon Voight, Dustin Hoffman, Sylvia Miles, Brenda Vaccaro. Drama.

Though “X-rated” means something different than it did in 1969, it’s still a badge of honor that Midnight Cowboy is the only film with that “for adults only” label to have won the Best Picture Oscar (Last Tango in Paris being the other great “X-rated” flick of the era). Midnight Cowboy is less shocking today; sexually, it’s not the graphic images that provide the punch it’s the intellectually complicated nature of the characters’ sexuality that still can move an audience. As a follow up to The Graduate, Dustin Hoffman proved he was more than a one-hit wonder and instead that he had a long and vital career ahead of him. It also deservedly made a star out of a little known pretty-boy actor named Jon Voight. And it also put British director John Schlesinger on the American A-list, a guy whose deep sensitivity and open homosexuality put him ahead of his time. The film’s theme song, “Everybody’s Talkin’” performed by Harry Nilsson, has become the iconic standard bearer for images of a lonely guy walking the streets of New York. Midnight Cowboy also is a fascinating peek at an era both for representation for how an artist works at a time when the movie studios were willing to take a chance on a grubby flick about a would-be male prostitute and his new BFF while also revealing a dark side to the Big Apple during what has sometimes been considered a golden age of self-expression.

Apparently screenwriter Waldo Salt (who was just emerging from two decades of being blacklisted) took a lot of liberties with James Leo Herlihy’s underground but acclaimed novel. A Texas dishwasher named Joe Buck (Voight) decides to drop his apron and take advantage of his good looks; he busses up to Manhattan under the illusion that it’s a city full of rich women and fairies. They need a real cowboy to show them what a true man is. Unfortunately life in the big city doesn’t turn out like he hoped. There’s competition in the cowboy hustler department and most people are not charmed by his act. He does finally hook up with a seemingly wealthy older woman but when he requests payment for his services, she turns the tables and he ends up paying her. Similar trysts with two men, a religious nut and a teenage boy (a young Bob Balaban), prove fruitless as Joe is kicked out of his pad and finds himself cold, hungry, and homeless.

After being taken and tricked by a dirty little weasel of a man, the peg-legged Enrico Rizzo aka Ratso (Hoffman), the two end up becoming buds with the gimpy and matted Ratso trying to show the big dumb cowboy the way of the streets and the con game, even sharing his condemned building shelter he squats in. Things look up as the guys get invited to a chic Andy Warhol-inspired hipster party (where real-life “Warhol superstars” Ultra Violet and Viva appear). Joe smokes some weed and goes on a groovy mind trip; he gets to experience what the Woodstock Generation in NYC is all about. He even meets a pretty socialite (Brenda Vaccaro) and finally makes some good cash for his stud services, though at first he has erection issues, but when she suggests maybe he’s gay, that wakes Little Joe right up and he shows her how they do it Texas-style.

Throughout the film Ratso’s cough is getting worse and his health deteriorates. We also slowly learn some Joe Buck back story through eerie flashbacks. He’s haunted by two women: his grandmother who raised him (their relationship had a sexual nature to it) and his ex-girlfriend who ended up in a mental institute after she and Joe were gang-raped by a pack of yahoos. Joe’s loneliness and Ratso’s illness bring them closer together; finally they decide to leave chilly New York for the sun of Miami Beach. On the bus ride there Joe dumps his cowboy costume for some preppy frat boy outfits, but then Ratso dies on the back of the bus (the second Hoffman flick in a row that ends with symbolism of a couple on a bus). Joe tries to hold on to Ratso’s dignity for him as he finally understands the meaning of friendship and, more importantly, manhood.

They say that cinematically it often takes a foreigner to truly understand the American dream. After the success of Darling and Far From the Madding Crowd, two films that criticize the British class system, Schlesinger here turned the big city ambitions of a country boy into the pathetic delusions of a Times Square hustler. And it wasn’t just Schlesinger—Sergio Leone and Sam Peckinpah were turning the most scared American cinema genre, the western, on it head while the modern West was being demystified with films like Hud and The Last Picture Show. Most importantly, though, to where Midnight Cowboy fit into its era, with the Vietnam War raging young people were questioning the myth of the American cowboy and its cult of John Wayne. Midnight Cowboy added to the conversation by declaring that it’s all one big lie (ironically John Wayne beat Hoffman and Voight for the Best Actor award at that year’s Oscars for a film, True Grit, which already felt stale by ’69).

Schlesinger followed Midnight Cowboy with a couple of interesting flicks: Sunday Bloody Sunday, The Day of the Locust, and Marathon Man, but then he spent the next 20 years trying unsuccessfully to connect with audiences, apparently losing the ability to pick good material and inspire his casts as he did so well in the earlier part of his career (one exception being The Falcon and the Snowman in ’85). But with Midnight Cowboy Schlesinger nailed it; the gritty street realism he created gave Hoffman and Voight room to give two of the most memorable performances of their careers. Schlesinger had hidden cameras planted so the actors could relate to actual people on the street, most famously with Hoffman’s reaction to a car almost hitting him, “I’m walking here!” But style and timing aside, what helps Midnight Cowboy stand the test of time is the relationship between the two characters. Sunday Bloody Sunday, Schlesinger’s next flick, was about the sexual relationship between two men; with Midnight Cowboy it’s not sexual, but there is an intimacy rarely seen at that time between two males on the screen—another reason audiences in ’69 were so shocked and why audiences today can so appreciate it.

_____________________

Midnight Cowboy was nominated for 8 Oscars including two for Best Actor (Dustin Hoffman, Jon Voight), Best Supporting Actress (Sylvia Miles), and Best Editing (Hugh Robertson) and won for Best Picture, Best Director (John Schlesinger), and Best Adapted Screenplay (Waldo Salt).

Apparently screenwriter Waldo Salt (who was just emerging from two decades of being blacklisted) took a lot of liberties with James Leo Herlihy’s underground but acclaimed novel. A Texas dishwasher named Joe Buck (Voight) decides to drop his apron and take advantage of his good looks; he busses up to Manhattan under the illusion that it’s a city full of rich women and fairies. They need a real cowboy to show them what a true man is. Unfortunately life in the big city doesn’t turn out like he hoped. There’s competition in the cowboy hustler department and most people are not charmed by his act. He does finally hook up with a seemingly wealthy older woman but when he requests payment for his services, she turns the tables and he ends up paying her. Similar trysts with two men, a religious nut and a teenage boy (a young Bob Balaban), prove fruitless as Joe is kicked out of his pad and finds himself cold, hungry, and homeless.

After being taken and tricked by a dirty little weasel of a man, the peg-legged Enrico Rizzo aka Ratso (Hoffman), the two end up becoming buds with the gimpy and matted Ratso trying to show the big dumb cowboy the way of the streets and the con game, even sharing his condemned building shelter he squats in. Things look up as the guys get invited to a chic Andy Warhol-inspired hipster party (where real-life “Warhol superstars” Ultra Violet and Viva appear). Joe smokes some weed and goes on a groovy mind trip; he gets to experience what the Woodstock Generation in NYC is all about. He even meets a pretty socialite (Brenda Vaccaro) and finally makes some good cash for his stud services, though at first he has erection issues, but when she suggests maybe he’s gay, that wakes Little Joe right up and he shows her how they do it Texas-style.

Throughout the film Ratso’s cough is getting worse and his health deteriorates. We also slowly learn some Joe Buck back story through eerie flashbacks. He’s haunted by two women: his grandmother who raised him (their relationship had a sexual nature to it) and his ex-girlfriend who ended up in a mental institute after she and Joe were gang-raped by a pack of yahoos. Joe’s loneliness and Ratso’s illness bring them closer together; finally they decide to leave chilly New York for the sun of Miami Beach. On the bus ride there Joe dumps his cowboy costume for some preppy frat boy outfits, but then Ratso dies on the back of the bus (the second Hoffman flick in a row that ends with symbolism of a couple on a bus). Joe tries to hold on to Ratso’s dignity for him as he finally understands the meaning of friendship and, more importantly, manhood.

They say that cinematically it often takes a foreigner to truly understand the American dream. After the success of Darling and Far From the Madding Crowd, two films that criticize the British class system, Schlesinger here turned the big city ambitions of a country boy into the pathetic delusions of a Times Square hustler. And it wasn’t just Schlesinger—Sergio Leone and Sam Peckinpah were turning the most scared American cinema genre, the western, on it head while the modern West was being demystified with films like Hud and The Last Picture Show. Most importantly, though, to where Midnight Cowboy fit into its era, with the Vietnam War raging young people were questioning the myth of the American cowboy and its cult of John Wayne. Midnight Cowboy added to the conversation by declaring that it’s all one big lie (ironically John Wayne beat Hoffman and Voight for the Best Actor award at that year’s Oscars for a film, True Grit, which already felt stale by ’69).

Schlesinger followed Midnight Cowboy with a couple of interesting flicks: Sunday Bloody Sunday, The Day of the Locust, and Marathon Man, but then he spent the next 20 years trying unsuccessfully to connect with audiences, apparently losing the ability to pick good material and inspire his casts as he did so well in the earlier part of his career (one exception being The Falcon and the Snowman in ’85). But with Midnight Cowboy Schlesinger nailed it; the gritty street realism he created gave Hoffman and Voight room to give two of the most memorable performances of their careers. Schlesinger had hidden cameras planted so the actors could relate to actual people on the street, most famously with Hoffman’s reaction to a car almost hitting him, “I’m walking here!” But style and timing aside, what helps Midnight Cowboy stand the test of time is the relationship between the two characters. Sunday Bloody Sunday, Schlesinger’s next flick, was about the sexual relationship between two men; with Midnight Cowboy it’s not sexual, but there is an intimacy rarely seen at that time between two males on the screen—another reason audiences in ’69 were so shocked and why audiences today can so appreciate it.

_____________________

Midnight Cowboy was nominated for 8 Oscars including two for Best Actor (Dustin Hoffman, Jon Voight), Best Supporting Actress (Sylvia Miles), and Best Editing (Hugh Robertson) and won for Best Picture, Best Director (John Schlesinger), and Best Adapted Screenplay (Waldo Salt).

Posted by:

Sean Sweeney

Feb 15, 2012 6:05pm