Movies We Like

The Heiress

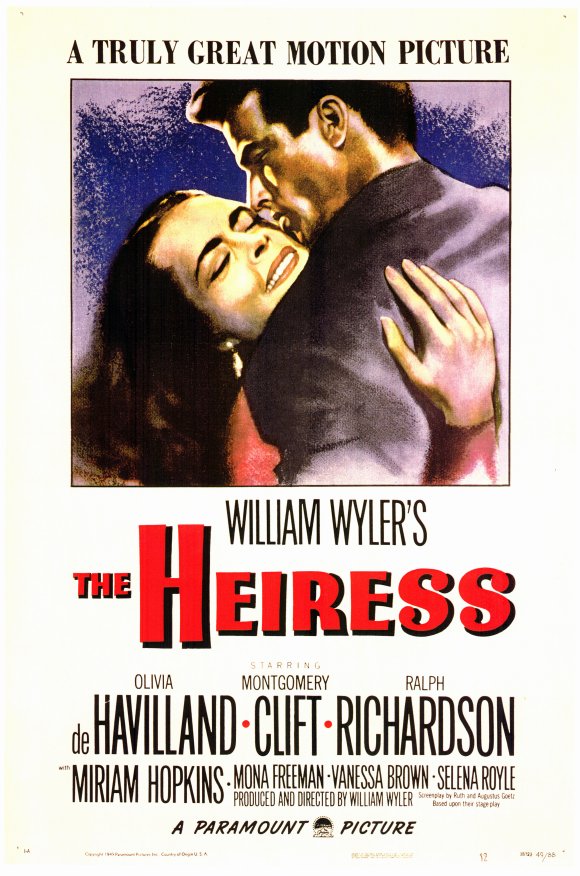

Dir: William Wyler, 1949. Starring: Olivia de Havilland, Montgomery Clift, Ralph Richardson. Classics.

In some ways Olivia de Havilland may be one of the more underrated actresses of her generation. She wasn’t as iconic as some of her peers like Katharine Hepburn or Bette Davis and not quite as beautiful as her rival sister, actress Joan Fontaine (Suspicion); instead of sexiness de Havilland brought a righteous intelligence to her roles. She was known throughout history mostly for playing Melanie in Gone with the Wind and for her association with the dashing actor Errol Flynn in their eight films together, most notably The Adventures of Robin Hood, They Died with Their Boots On, and Captain Blood. She had a number of other relevant roles in the ‘40s including The Snake Pit, Not as a Stranger, and Hold Back the Dawn. de Havilland won two Oscars: first, for the melodrama To Each His Own and then for her most interesting performance in William Wyler’s The Heiress, based on the Henry James novel Washington Square.

The late 1800s in New York City: mousy spinster Catherine Sloper (de Havilland) lives with her wise and widowed doctor father, Austin (Ralph Richardson who in real life was only 14-years-older than de Havilland), and her doting aunt, Lavinia (Miriam Hopkins). Catherine’s utterly plain and shy and unexceptional in every manner, which makes it more surprising when the handsome Morris Townsend (Montgomery Clift) shows up in town from California and immediately takes an interest in Catherine, wooing her with all his pretty-boy charms. Romanced for the first time, Catherine comes alive, becoming a giddy school girl utterly smitten with her suitor. The two lovebirds become engaged and plan to elope, but Austin doesn’t trust the rogue, knowing a playboy gold digger when he sees one; he tells Catherine he will disinherit her if she marries him. He also hurts his daughter when he coldly explains that Morris could have any young hottie in NY and why would he chose her if it’s not for the money? Proving Dad right, with the money not coming Morris doesn’t show up for the elopement and rushes back to California. Brokenhearted, Catherine realizes for the first time she really is a dullard who can only find love if she’s loaded with cash. And then to make matters worse, Austin dies and Catherine goes from a happy simpleton to a cold heiress. Years later Morris returns to try and get in on the money again, but the new self-empowered Catherine only pretends to buy into his oily trap and turns the tables on him instead, accepting a lifetime of loneliness to keep her dignity.

Throughout the ‘30s,’ 40s, and ‘50s William Wyler was a big-time director with films ranging from The Best Years of Our Lives and Jezebel to Wuthering Heights, but like de Havilland, his once shining career may be less remembered than his more celebrated peers like Orson Welles, Alfred Hitchcock, Howard Hawks, and John Ford, who all had a more personally clear auteur style than him. This simple, almost dated visual style of The Heiress is an example of where he was less ambitious than the others. Adapted from a popular stage play by Ruth and Augustus Goetz, the film barely opens it up from its one-set roots (and it obviously is a set). They live at Washington Square Park but we never see it; the beauty of New York is mentioned many times but rarely backed up on camera. But with his use of gothic, almost noirish shadows and high angles, Wyler is able to create a gloomy claustrophobic atmosphere; you can understand why Catherine is so eager to escape it.

Not the visuals, no, what Wyler did great was milk interesting performances from his casts and The Heiress is no exception. In only his third film, Clift is at his least methody, whereas for the rest of his career, even in his best film, A Place in the Sun, he would have that effective brooding, tortured style. As Morris, Clift shows some of that famous sensitivity, but for the most part he lets the audience see why Catherine would be taken by him, his overt attractiveness. But he never asks us to love him; for a young up-and-coming leading man, it’s a gutsy performance from Clift. For the great Shakespearean actor Ralph Richardson, The Heiress was a follow-up to his best known performance in Carol Reed’s brilliant The Fallen Idol; his icy father wants the best for his daughter but in the end he never really respects her. But de Havilland is the real star here and, along with Gone with the Wind, this is her signature role. Like so many women in racy literature from that era, Catherine’s trapped in her social status; without a husband she is doomed to a life of knitting and quiet reserve. de Havilland plays Catherine’s character arc masterfully, going from almost socially retarded to a black widow. The classically attractive de Havilland has remade herself as a dowdy spinster; instead of going the Hepburn route and playing overly perky, or overly bitchy like Davis, she is understated and even placid—not the adjective that history always remembers.

____________

The Heiress was nominated for 8 Oscars including Best Picture, Best Director (William Wyler), Best Cinematography (Leo Tover), Best Supporting Actor (Ralph Richardson), and won for Best Music (Aaron Copland), Best Costume Design (Edith Head, Gile Steele), Best Art Direction, and Best Actress (Olivia de Havilland).

The late 1800s in New York City: mousy spinster Catherine Sloper (de Havilland) lives with her wise and widowed doctor father, Austin (Ralph Richardson who in real life was only 14-years-older than de Havilland), and her doting aunt, Lavinia (Miriam Hopkins). Catherine’s utterly plain and shy and unexceptional in every manner, which makes it more surprising when the handsome Morris Townsend (Montgomery Clift) shows up in town from California and immediately takes an interest in Catherine, wooing her with all his pretty-boy charms. Romanced for the first time, Catherine comes alive, becoming a giddy school girl utterly smitten with her suitor. The two lovebirds become engaged and plan to elope, but Austin doesn’t trust the rogue, knowing a playboy gold digger when he sees one; he tells Catherine he will disinherit her if she marries him. He also hurts his daughter when he coldly explains that Morris could have any young hottie in NY and why would he chose her if it’s not for the money? Proving Dad right, with the money not coming Morris doesn’t show up for the elopement and rushes back to California. Brokenhearted, Catherine realizes for the first time she really is a dullard who can only find love if she’s loaded with cash. And then to make matters worse, Austin dies and Catherine goes from a happy simpleton to a cold heiress. Years later Morris returns to try and get in on the money again, but the new self-empowered Catherine only pretends to buy into his oily trap and turns the tables on him instead, accepting a lifetime of loneliness to keep her dignity.

Throughout the ‘30s,’ 40s, and ‘50s William Wyler was a big-time director with films ranging from The Best Years of Our Lives and Jezebel to Wuthering Heights, but like de Havilland, his once shining career may be less remembered than his more celebrated peers like Orson Welles, Alfred Hitchcock, Howard Hawks, and John Ford, who all had a more personally clear auteur style than him. This simple, almost dated visual style of The Heiress is an example of where he was less ambitious than the others. Adapted from a popular stage play by Ruth and Augustus Goetz, the film barely opens it up from its one-set roots (and it obviously is a set). They live at Washington Square Park but we never see it; the beauty of New York is mentioned many times but rarely backed up on camera. But with his use of gothic, almost noirish shadows and high angles, Wyler is able to create a gloomy claustrophobic atmosphere; you can understand why Catherine is so eager to escape it.

Not the visuals, no, what Wyler did great was milk interesting performances from his casts and The Heiress is no exception. In only his third film, Clift is at his least methody, whereas for the rest of his career, even in his best film, A Place in the Sun, he would have that effective brooding, tortured style. As Morris, Clift shows some of that famous sensitivity, but for the most part he lets the audience see why Catherine would be taken by him, his overt attractiveness. But he never asks us to love him; for a young up-and-coming leading man, it’s a gutsy performance from Clift. For the great Shakespearean actor Ralph Richardson, The Heiress was a follow-up to his best known performance in Carol Reed’s brilliant The Fallen Idol; his icy father wants the best for his daughter but in the end he never really respects her. But de Havilland is the real star here and, along with Gone with the Wind, this is her signature role. Like so many women in racy literature from that era, Catherine’s trapped in her social status; without a husband she is doomed to a life of knitting and quiet reserve. de Havilland plays Catherine’s character arc masterfully, going from almost socially retarded to a black widow. The classically attractive de Havilland has remade herself as a dowdy spinster; instead of going the Hepburn route and playing overly perky, or overly bitchy like Davis, she is understated and even placid—not the adjective that history always remembers.

____________

The Heiress was nominated for 8 Oscars including Best Picture, Best Director (William Wyler), Best Cinematography (Leo Tover), Best Supporting Actor (Ralph Richardson), and won for Best Music (Aaron Copland), Best Costume Design (Edith Head, Gile Steele), Best Art Direction, and Best Actress (Olivia de Havilland).

Posted by:

Sean Sweeney

Mar 27, 2012 8:15am