Movies We Like

Reds

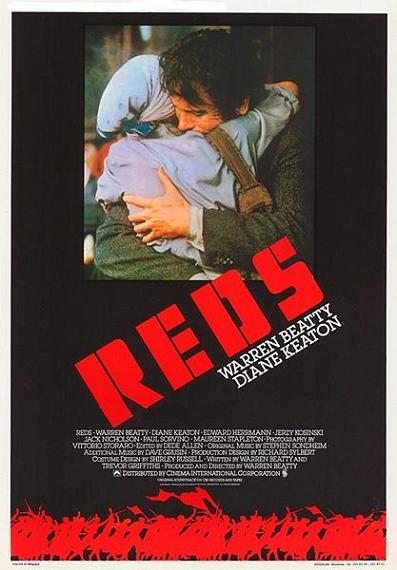

Dir: Warren Beatty, 1981. Starring: Warren Beatty, Jack Nicholson, Diane Keaton, Edward Herrmann. Drama.

In 1981, with newly elected rah-rah American president Ronald Reagan taking office, an anti-Communist, anti-Soviet ardor was in full swing. So it was extra amazingly audacious that pretty-boy actor Warren Beatty was able to get his giant bio of Communist journalist John Reed made. Reed, the only American buried in Russia’s Kremlin, isn’t exactly a household name and Reds the movie, clocking in at an epic 194 minutes, wasn’t exactly a sure thing at the box-office (matter of fact, despite winning a bunch of awards, it was considered a financial disappointment in its day). Reds really is a tribute to the passion of Warren Beatty’s grand vision; he produced, directed, and co-wrote the screenplay with British playwright Trevor Griffiths (with uncredited contributions from Elaine May) and managed to put together an impressive cast to back him up (Diane Keaton, Jack Nicholson, Edward Herrmann, Paul Sorvino, Maureen Stapleton, Gene Hackman, etc). Ironic: a rich movie star makes a big expensive movie (with corporate funds) about an anti-wealth guy. In the Doctor Zhivago tradition, Reds is one of those sweeping literate love stories which was shot for over a year in five different countries; but underneath that sweep it’s a very personal and intimate little movie.

After covering events in Russia, journalist John Reed (Beatty) returns to his home town of Portland to raise money for his ultra-left newspaper. There, he meets and has a fling with a married socialite named Louise Bryant (Keaton) and invites her back to New York's bohemian Greenwich Village where they both hang with many of the famous radicals of their day, like the outspoken anarchist Emma Goldman (Stapleton). Reed encourages Bryant to become a writer herself; she develops her own form of ahead-of- her-time feminism while he throws himself deeper into the Communist Party. After the couple moves to Provincetown, Massachusetts, Reed travels the country to cover the presidential election, while Bryant begins an affair with Reed’s friend, the tortured playwright Eugene O’Neill (Nicholson), the one intellectual who seems to respect her. Then, Reed and Bryant patch things up and first travel to write about the war in Europe (that would be WWI) and then to cover the revolution in Russia of 1917. And that’s just the first half.

The second half has the two breaking up and reuniting all over the world. Reed becomes disillusioned with spreading his beloved workers revolution to the United States, finding there’s more politics than idealism here and he’s disappointed by the stiffness of the Communist Party of Russia. He also begins a slow death march from kidney failure, and after a long stay in Russia, Bryant finally rejoins to comfort him as he dies.

While in Russia, Reed is considered a great American. He was only really famous here for his book on the Revolution, Ten Days That Shock the World. But the film manages to make him and Bryant seem like tabloid celebrities by using real life witnesses who knew them, or knew of them, to fill in the gaps of the script with anecdotes and reflections, made up of dozens of old radicals, artists, and historians such as Robert Nash Baldwin (founder of the ACLU), entertainer George Jessel, dirty book writer Henry Miller, and acclaimed journalist Adela Rogers St. Johns.

Beatty had already struck gold as an actor/producer 13 years earlier with the classic Bonnie and Clyde, becoming a major Hollywood power player. Then, 10 years later he produced, starred, and co-directed (with Buck Henry) Heaven Can Wait. But that was an easy sell, a light comedy. Reds is big in a David Lean way, but with less heroic qualities than his films. After writing his famous book, most of Reed’s life before his death was spent refereeing spats between American Socialists and Communists, not a story you can picture most movie biz execs seeing dollar signs behind. But Beatty read the book and went out and made the film; maybe those who knew it wouldn’t make back its hefty price tag were right, but what he made is sometimes nearly astounding. Reds has an almost Euro-epic feel (think Bertolucci’s 1900), meaning it’s challenging and not easy to fall in love with. It has a lot of ideas but it doesn’t hand them to the audience; instead, it’s the audience’s job to reach into the film to find the emotion. The genius in Reds is that even if you can’t identify with old radicals discussing politics (which is what much of the movie is), there is a passionate international love story at play here—a dying breed. Though films like The English Patient and Out of Africa would continue the tradition, none of those films would find such electricity, wrung from such unusual sources.

Outside of her work with Woody Allen, this is the performance of Keaton’s career. She gives Bryant a complicated, spunky warmth; she wants to be a simple, devoted lover to a man she admires, but she also knows she is on the brink of changing social attitudes and can’t help but lead them. With the exception of his mega performance in Terms of Endearment, Reds is easily the most interesting work by Nicholson in the ‘80s. After chomping at the scenery in The Shining, this is a brief but welcome return to a more subtle Nicholson. Beatty brings his usual quirks and stuttering mannerisms to Reed, which always seemed to be Beatty’s way of distracting against his natural good looks. This, for me, made Beatty a more interesting actor than his pretty boy contemporary, Robert Redford, but probably why Redford was always a much bigger box office draw.

Reds obviously shares some historical crossover timelines with the Russian characters in Lean’s sudsy Doctor Zhivago, and it is an utterly fascinating era. The other thing they share in that landscape is a sexual passion; the Russian Revolution might’ve been romanticized by many, but was certainly never thought of as sexy until Zhivago’s Omar Sharif and Julie Christie came along. Like all good Communist propaganda, Reds is beyond sex; Keaton and Beatty have a rare adult onscreen charisma together and, in the film’s most famous scene, a long embrace in a Russian train station after being separated from each other for a long time. Their longing and love for each other is obvious and moving, but instead of jumping into bed, it feels like they are ready for a long night of talking together—two comrades in love.

__________________

Reds was nominated for 12 Oscars and won 3 including Best Supporting Actress (Maureen Stapleton), Best Cinematography (Vittorio Storaro), and Best Director (Warren Beatty).

After covering events in Russia, journalist John Reed (Beatty) returns to his home town of Portland to raise money for his ultra-left newspaper. There, he meets and has a fling with a married socialite named Louise Bryant (Keaton) and invites her back to New York's bohemian Greenwich Village where they both hang with many of the famous radicals of their day, like the outspoken anarchist Emma Goldman (Stapleton). Reed encourages Bryant to become a writer herself; she develops her own form of ahead-of- her-time feminism while he throws himself deeper into the Communist Party. After the couple moves to Provincetown, Massachusetts, Reed travels the country to cover the presidential election, while Bryant begins an affair with Reed’s friend, the tortured playwright Eugene O’Neill (Nicholson), the one intellectual who seems to respect her. Then, Reed and Bryant patch things up and first travel to write about the war in Europe (that would be WWI) and then to cover the revolution in Russia of 1917. And that’s just the first half.

The second half has the two breaking up and reuniting all over the world. Reed becomes disillusioned with spreading his beloved workers revolution to the United States, finding there’s more politics than idealism here and he’s disappointed by the stiffness of the Communist Party of Russia. He also begins a slow death march from kidney failure, and after a long stay in Russia, Bryant finally rejoins to comfort him as he dies.

While in Russia, Reed is considered a great American. He was only really famous here for his book on the Revolution, Ten Days That Shock the World. But the film manages to make him and Bryant seem like tabloid celebrities by using real life witnesses who knew them, or knew of them, to fill in the gaps of the script with anecdotes and reflections, made up of dozens of old radicals, artists, and historians such as Robert Nash Baldwin (founder of the ACLU), entertainer George Jessel, dirty book writer Henry Miller, and acclaimed journalist Adela Rogers St. Johns.

Beatty had already struck gold as an actor/producer 13 years earlier with the classic Bonnie and Clyde, becoming a major Hollywood power player. Then, 10 years later he produced, starred, and co-directed (with Buck Henry) Heaven Can Wait. But that was an easy sell, a light comedy. Reds is big in a David Lean way, but with less heroic qualities than his films. After writing his famous book, most of Reed’s life before his death was spent refereeing spats between American Socialists and Communists, not a story you can picture most movie biz execs seeing dollar signs behind. But Beatty read the book and went out and made the film; maybe those who knew it wouldn’t make back its hefty price tag were right, but what he made is sometimes nearly astounding. Reds has an almost Euro-epic feel (think Bertolucci’s 1900), meaning it’s challenging and not easy to fall in love with. It has a lot of ideas but it doesn’t hand them to the audience; instead, it’s the audience’s job to reach into the film to find the emotion. The genius in Reds is that even if you can’t identify with old radicals discussing politics (which is what much of the movie is), there is a passionate international love story at play here—a dying breed. Though films like The English Patient and Out of Africa would continue the tradition, none of those films would find such electricity, wrung from such unusual sources.

Outside of her work with Woody Allen, this is the performance of Keaton’s career. She gives Bryant a complicated, spunky warmth; she wants to be a simple, devoted lover to a man she admires, but she also knows she is on the brink of changing social attitudes and can’t help but lead them. With the exception of his mega performance in Terms of Endearment, Reds is easily the most interesting work by Nicholson in the ‘80s. After chomping at the scenery in The Shining, this is a brief but welcome return to a more subtle Nicholson. Beatty brings his usual quirks and stuttering mannerisms to Reed, which always seemed to be Beatty’s way of distracting against his natural good looks. This, for me, made Beatty a more interesting actor than his pretty boy contemporary, Robert Redford, but probably why Redford was always a much bigger box office draw.

Reds obviously shares some historical crossover timelines with the Russian characters in Lean’s sudsy Doctor Zhivago, and it is an utterly fascinating era. The other thing they share in that landscape is a sexual passion; the Russian Revolution might’ve been romanticized by many, but was certainly never thought of as sexy until Zhivago’s Omar Sharif and Julie Christie came along. Like all good Communist propaganda, Reds is beyond sex; Keaton and Beatty have a rare adult onscreen charisma together and, in the film’s most famous scene, a long embrace in a Russian train station after being separated from each other for a long time. Their longing and love for each other is obvious and moving, but instead of jumping into bed, it feels like they are ready for a long night of talking together—two comrades in love.

__________________

Reds was nominated for 12 Oscars and won 3 including Best Supporting Actress (Maureen Stapleton), Best Cinematography (Vittorio Storaro), and Best Director (Warren Beatty).

Posted by:

Sean Sweeney

Apr 25, 2012 5:08pm