Movies We Like

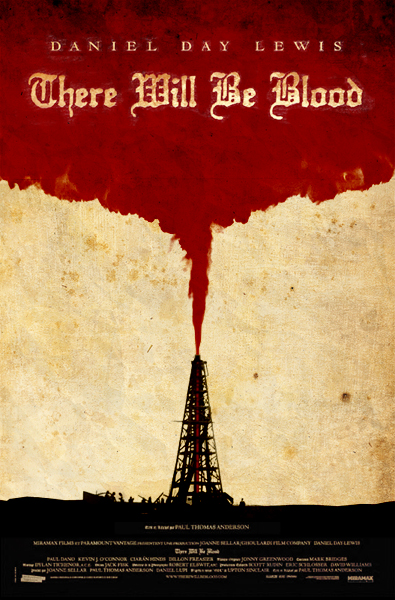

There Will Be Blood

Dir: Paul Thomas Anderson, 2007. Starring: Daniel Day Lewis, Paul Dano, Ciaran Hinds, Kevin J. O'Connor. Drama.

For director/writer Paul Thomas Anderson, his first film Hard Eight was a solid gambling thriller while Punch-Drunk Love gave him quirky Lynchian street cred, but it was his double dose of sprawling LA ensemble pieces Magnolia and Boogie Nights that put him in the big, big-time. Though those are two dazzlingly shot and acted flicks, there is a sense of Altman-esqe gimmickry and MapQuest symmetry about them. It really was his fifth feature, There Will Be Blood, which made Anderson more then just a hip taste of the day. Apparently the film was partially inspired by Upton Sinclair’s 1927 novel, Oil!, with the setting moved from the 1920s to the turn of the century. The film works best when sticking to the source material, detailing the beginnings of the oil boom; it tends to loose itself when veering off-course into Anderson’s morality battle. Regardless, it’s always watchable thanks first and foremost to the epic performance from the great Irish actor Daniel Day-Lewis, who channels the voice, look, and attitude of director/actor John Huston (even more accurately then Clint Eastwood did in White Hunter Black Heart). There Will Be Blood proves that when Anderson has the right, focused material he has as much clear-eyed vision as anyone making movies these days.

Spanning decades in the life and career of Daniel Plainview (Day-Lewis), a prospector who gets into the oil game, the films opens with a stunning dialogue-free 15 minutes as Plainview digs for oil and adopts a baby boy from a worker who was killed. He has a knack for finding oil and becomes more and more successful. Though he is a greedy manipulator he seems to be a devoted dad, referring to his son as his business partner. However, after the kid goes deaf in an on-site accident he seems to lose his patience for fathering. Getting a tip from a young man named Paul Sunday (Paul Dano) about a piece of land that may have oil, he swindles the family out of their land and gets very rich with the oil he takes from their ground. Unfortunately, Paul’s twin brother Eli (also Dano, which at first seems confusing) is a true believer preacher who becomes a lifelong headache for the faithless entrepreneur. He also is joined briefly by a guy claiming to be his long-lost half brother (Kevin J. O’Connor) and has minor spats with the major oil companies.

It’s refreshing that Anderson doesn’t spell out too clearly what drives the characters; ambiguity can make for a more challenging watch. But sometimes Plainview’s aloofness can be frustrating to the viewer. The final timeline to the film, a good 20 years on from where it started in 1902, has Plainview now hostile and raging drunk living in a Citizen Kane-like lonely mansion with a bowling alley. He always drank but how did he reach such an aggressive state? This leads to a particularly ugly final meeting with his now grown son and then to an even more tragic ending with Eli, now a successful radio preacher looking to make a buck. The film ends with a beautifully messy final shot that completely cops a feel from Kubrick. Like much of the movie (and most of Anderson’s work) the flaws and frustrations are easy to overlook because the guy brings such craftsmanship and conviction to every frame, even moments that fall flat are still more compelling than the average film-going experience.

Again, bringing his legendary focus and commitment to the role, Day-Lewis gives one of the great performances of the decade, as he did in the ‘90s with his work on In the Name of the Father. Toning it down a few notes from his exciting but hammy performance in the overwrought Gangs of New York, he’s all old-school manly businessman and dangerous adventurer, and is utterly believable in the period. Dano brings a simple minimalism to his acting that’s admirable but it also makes him a less exciting antagonist to Day-Lewis’s intensity. The next star of the film would have to be the score by Johnny Greenwood (of the band Radiohead), mixing traditional orchestrated classical music with experimental sounds almost in the Phillip Glass/ Ennio Morricone tradition. And like John Ford’s collaboration with the great cinematographer Gregg Toland on The Grapes of Wrath, Anderson worked with Director of Photography Robert Elswit for the fifth straight film, creating precise landscapes and images that look straight out of photographs of the era.

Whether it is or not, There Will Be Blood looks and just feels like a masterpiece. But it’s not just the surface; unlike, say, Terrence Malick’s beautiful bore Days of Heaven, There Will Be Blood is always entertaining; even if Plainview’s character arc is a little jagged it’s never anything less than utterly absorbing. It’s a film that will stand the test of time; it’s sure to always be considered one of the more vital films of the decade. The performances, the look, the sound—it’s all a tribute to the ringmaster Anderson. Like only a handful of his contemporaries, he’s now assured, at least for a while, that any film he makes will be considered an event and must be given our full attention. Yes, in other words (the more pretentious way), There Will Be Blood officially makes Anderson an auteur of the highest regard.

_______________

There Will Be Blood was nominated for eight Oscars and won for two including Best Cinematography (Robert Elswit) and Best Actor (Daniel Day-Lewis).

Spanning decades in the life and career of Daniel Plainview (Day-Lewis), a prospector who gets into the oil game, the films opens with a stunning dialogue-free 15 minutes as Plainview digs for oil and adopts a baby boy from a worker who was killed. He has a knack for finding oil and becomes more and more successful. Though he is a greedy manipulator he seems to be a devoted dad, referring to his son as his business partner. However, after the kid goes deaf in an on-site accident he seems to lose his patience for fathering. Getting a tip from a young man named Paul Sunday (Paul Dano) about a piece of land that may have oil, he swindles the family out of their land and gets very rich with the oil he takes from their ground. Unfortunately, Paul’s twin brother Eli (also Dano, which at first seems confusing) is a true believer preacher who becomes a lifelong headache for the faithless entrepreneur. He also is joined briefly by a guy claiming to be his long-lost half brother (Kevin J. O’Connor) and has minor spats with the major oil companies.

It’s refreshing that Anderson doesn’t spell out too clearly what drives the characters; ambiguity can make for a more challenging watch. But sometimes Plainview’s aloofness can be frustrating to the viewer. The final timeline to the film, a good 20 years on from where it started in 1902, has Plainview now hostile and raging drunk living in a Citizen Kane-like lonely mansion with a bowling alley. He always drank but how did he reach such an aggressive state? This leads to a particularly ugly final meeting with his now grown son and then to an even more tragic ending with Eli, now a successful radio preacher looking to make a buck. The film ends with a beautifully messy final shot that completely cops a feel from Kubrick. Like much of the movie (and most of Anderson’s work) the flaws and frustrations are easy to overlook because the guy brings such craftsmanship and conviction to every frame, even moments that fall flat are still more compelling than the average film-going experience.

Again, bringing his legendary focus and commitment to the role, Day-Lewis gives one of the great performances of the decade, as he did in the ‘90s with his work on In the Name of the Father. Toning it down a few notes from his exciting but hammy performance in the overwrought Gangs of New York, he’s all old-school manly businessman and dangerous adventurer, and is utterly believable in the period. Dano brings a simple minimalism to his acting that’s admirable but it also makes him a less exciting antagonist to Day-Lewis’s intensity. The next star of the film would have to be the score by Johnny Greenwood (of the band Radiohead), mixing traditional orchestrated classical music with experimental sounds almost in the Phillip Glass/ Ennio Morricone tradition. And like John Ford’s collaboration with the great cinematographer Gregg Toland on The Grapes of Wrath, Anderson worked with Director of Photography Robert Elswit for the fifth straight film, creating precise landscapes and images that look straight out of photographs of the era.

Whether it is or not, There Will Be Blood looks and just feels like a masterpiece. But it’s not just the surface; unlike, say, Terrence Malick’s beautiful bore Days of Heaven, There Will Be Blood is always entertaining; even if Plainview’s character arc is a little jagged it’s never anything less than utterly absorbing. It’s a film that will stand the test of time; it’s sure to always be considered one of the more vital films of the decade. The performances, the look, the sound—it’s all a tribute to the ringmaster Anderson. Like only a handful of his contemporaries, he’s now assured, at least for a while, that any film he makes will be considered an event and must be given our full attention. Yes, in other words (the more pretentious way), There Will Be Blood officially makes Anderson an auteur of the highest regard.

_______________

There Will Be Blood was nominated for eight Oscars and won for two including Best Cinematography (Robert Elswit) and Best Actor (Daniel Day-Lewis).

Posted by:

Sean Sweeney

Jun 1, 2012 5:07pm