Movies We Like

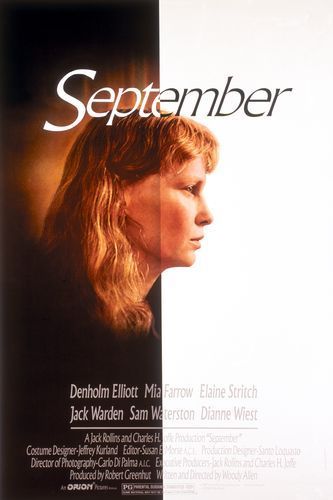

September

Dir: Woody Allen, 1987. Starring: Elaine Strich, Denholm Elliott, Mia Farrow. Comedy.

“It’s hell gettin’ older, especially when you feel 21 inside.”

— A sobering reflection made by the aging Diane, brashly played by the vibrant, and still very alive at 86, Elaine Stritch, in Woody Allen’s 1987 drama, September.

The film centers on Lane, a fragile and confused woman in her early fifties, played by Mia Farrow. After having moved into her summer home in Vermont for some much needed mental rest, Lane’s familial, platonic, and romantic relationships unravel at the arrival of autumn.

The plot of September, taking place over the few remaining days of the summer, floats through the home from room to room, mostly centering on a love triangle, or really, love train, secretly developing amongst the characters. Howard loves Lane, but she in fact loves Peter who in turn loves Lane’s friend Stephanie who is already unhappily married with children. This potential fodder for comedy, Woody Allen’s challah and butter, is instead treated and explored as the stuff of a serious stage piece, filled with the morose blend of emotionally heavy dialogue and restrained expression normally found off-off-off Broadway.

But in September, which for all intents and purposes is a filmed play, the love triangle is no laughing matter. The characters, all in their early to mid-fifties, find themselves at a complete loss as they enter the autumn of their lives. The triangle’s unrequited love takes an appropriate and subtle backseat to the feeling of regret and melancholy gnawing at the middle-aged dreamers. Lane desires a fresh start with a new career, new love, and a new apartment. Peter wants artistic and commercial success as a (yep, you guessed it) writer. Stephanie wants out of her loveless marriage. All three express a yearning for something more and disillusionment with where they thought they’d be at age 50. Even Lane’s mother, played by the tenacious and even-right-now still alive Elaine Stritch, feels the insecurity of having lived a valuable life.

This film, along with Another Woman (made the next year in 1988), presents a more 'serious' departure for Allen as he himself entered his 50s. Both films (made after the romantically nostalgic Radio Days) pair as both a cathartic and sobering stock-taking of life lived past the half-way point. Questions of universal meaning, the lasting or maybe fleeting nature of love, and the reluctant perspective of hope are carefully and pensively wrestled with by Allen. Through the complications of human relationships, Allen fleshes out these ideas, bouncing them off of childhood friends, colleagues, and adult children. Interestingly, in both instances, his protagonists are women. And in both, there’s an older, more introspective voice at work. And if not for the perspective of time and lighter, later comedies like Mighty Aphrodite, Deconstructing Harry, and Anything Else, one might begin to wonder if he or she could ever expect another neurotic joke about masturbation, et al. And while Allen’s sullen dramatic flair during his “Bergman” era irked even his most ardent fans, there is an undeniable and satisfactory catharsis in facing the inescapable road of aging and the inevitable destination of mortality. His characters feel regret, fear, and hope; and they do so in the context of spouses, parents, siblings, children, friends, coworkers, and strangers. As Allen’s characters relate to us their feelings, we are emotionally moved to ponder our own relationships, our own purpose. Because of this, the trilogy of Radio Days, September, and Another Woman may be Woody Allen's most personally vulnerable films. But probably most would disagree, and in fact, most have, as neither September nor Another Woman has aged well in the Woody Allen canon.

In the case of September, the film is minor Woody Allen. The classic W.A. staples are there: the witty dialogue, the insecurely flawed characters, the cheating on one another (although the overall feel is more Chekhov or Cassavetes than Allen). But from a technical or artistic standpoint, September is a very good play that was blocked and performed in front of a shooting camera. The house, built on a soundstage in New York’s Kaufman Astoria Studios, serves as the sole location for the film. The farthest the audience ventures out is to the front porch and the resulting feeling is suffocating. The summer vacation home is somewhat sparingly decorated with pastel walls and brown furniture giving an undecided and unsettled backdrop for the characters. Even Mia Farrow’s Lane is mousy and unkempt, lacking makeup and perpetually swimming in a large button-down men’s dress shirt. As the outside light floods the house, washing out any vibrancy of color, an overall feeling of blandness takes place. The only warmth and contrast occur when the electricity goes out and, by candlelight, certain characters express their deep-residing feelings for each other. It is an effective atmosphere that uses the fall weather change as both a reflection and setting for the characters’ shifting life stages.

The performances are excellent. Both reserved and natural, the actors take their time with themselves and each other. The women especially, as is common with Allen’s films, carry the emotional lion’s share of the film. This is mainly due to the even-still-right now alive at 86 and very vibrant Elaine Stritch, whose charismatic turn as the well-worn mother steals every scene she's in. With her gravelly voice bordering somewhere between Phyllis Diller and Frankie Five Fingers from The Godfather Part II, Stritch brings the only levity to this otherwise dire situation.

In short, September will probably interest either devoted Woody Allen fans or people who really don’t like him at all. While those in the latter camp may welcome the character-driven drama/departure from the usual comedic fare, the former will appreciate, along with Radio Days and Another Woman, the filmmaker’s sharing of his existential foray into middle age.

— A sobering reflection made by the aging Diane, brashly played by the vibrant, and still very alive at 86, Elaine Stritch, in Woody Allen’s 1987 drama, September.

The film centers on Lane, a fragile and confused woman in her early fifties, played by Mia Farrow. After having moved into her summer home in Vermont for some much needed mental rest, Lane’s familial, platonic, and romantic relationships unravel at the arrival of autumn.

The plot of September, taking place over the few remaining days of the summer, floats through the home from room to room, mostly centering on a love triangle, or really, love train, secretly developing amongst the characters. Howard loves Lane, but she in fact loves Peter who in turn loves Lane’s friend Stephanie who is already unhappily married with children. This potential fodder for comedy, Woody Allen’s challah and butter, is instead treated and explored as the stuff of a serious stage piece, filled with the morose blend of emotionally heavy dialogue and restrained expression normally found off-off-off Broadway.

But in September, which for all intents and purposes is a filmed play, the love triangle is no laughing matter. The characters, all in their early to mid-fifties, find themselves at a complete loss as they enter the autumn of their lives. The triangle’s unrequited love takes an appropriate and subtle backseat to the feeling of regret and melancholy gnawing at the middle-aged dreamers. Lane desires a fresh start with a new career, new love, and a new apartment. Peter wants artistic and commercial success as a (yep, you guessed it) writer. Stephanie wants out of her loveless marriage. All three express a yearning for something more and disillusionment with where they thought they’d be at age 50. Even Lane’s mother, played by the tenacious and even-right-now still alive Elaine Stritch, feels the insecurity of having lived a valuable life.

This film, along with Another Woman (made the next year in 1988), presents a more 'serious' departure for Allen as he himself entered his 50s. Both films (made after the romantically nostalgic Radio Days) pair as both a cathartic and sobering stock-taking of life lived past the half-way point. Questions of universal meaning, the lasting or maybe fleeting nature of love, and the reluctant perspective of hope are carefully and pensively wrestled with by Allen. Through the complications of human relationships, Allen fleshes out these ideas, bouncing them off of childhood friends, colleagues, and adult children. Interestingly, in both instances, his protagonists are women. And in both, there’s an older, more introspective voice at work. And if not for the perspective of time and lighter, later comedies like Mighty Aphrodite, Deconstructing Harry, and Anything Else, one might begin to wonder if he or she could ever expect another neurotic joke about masturbation, et al. And while Allen’s sullen dramatic flair during his “Bergman” era irked even his most ardent fans, there is an undeniable and satisfactory catharsis in facing the inescapable road of aging and the inevitable destination of mortality. His characters feel regret, fear, and hope; and they do so in the context of spouses, parents, siblings, children, friends, coworkers, and strangers. As Allen’s characters relate to us their feelings, we are emotionally moved to ponder our own relationships, our own purpose. Because of this, the trilogy of Radio Days, September, and Another Woman may be Woody Allen's most personally vulnerable films. But probably most would disagree, and in fact, most have, as neither September nor Another Woman has aged well in the Woody Allen canon.

In the case of September, the film is minor Woody Allen. The classic W.A. staples are there: the witty dialogue, the insecurely flawed characters, the cheating on one another (although the overall feel is more Chekhov or Cassavetes than Allen). But from a technical or artistic standpoint, September is a very good play that was blocked and performed in front of a shooting camera. The house, built on a soundstage in New York’s Kaufman Astoria Studios, serves as the sole location for the film. The farthest the audience ventures out is to the front porch and the resulting feeling is suffocating. The summer vacation home is somewhat sparingly decorated with pastel walls and brown furniture giving an undecided and unsettled backdrop for the characters. Even Mia Farrow’s Lane is mousy and unkempt, lacking makeup and perpetually swimming in a large button-down men’s dress shirt. As the outside light floods the house, washing out any vibrancy of color, an overall feeling of blandness takes place. The only warmth and contrast occur when the electricity goes out and, by candlelight, certain characters express their deep-residing feelings for each other. It is an effective atmosphere that uses the fall weather change as both a reflection and setting for the characters’ shifting life stages.

The performances are excellent. Both reserved and natural, the actors take their time with themselves and each other. The women especially, as is common with Allen’s films, carry the emotional lion’s share of the film. This is mainly due to the even-still-right now alive at 86 and very vibrant Elaine Stritch, whose charismatic turn as the well-worn mother steals every scene she's in. With her gravelly voice bordering somewhere between Phyllis Diller and Frankie Five Fingers from The Godfather Part II, Stritch brings the only levity to this otherwise dire situation.

In short, September will probably interest either devoted Woody Allen fans or people who really don’t like him at all. While those in the latter camp may welcome the character-driven drama/departure from the usual comedic fare, the former will appreciate, along with Radio Days and Another Woman, the filmmaker’s sharing of his existential foray into middle age.

Posted by:

Robbie Ikegami

Dec 7, 2011 6:24pm