Movies We Like

Down by Law

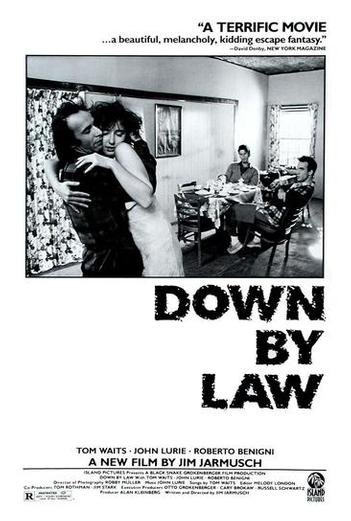

Dir: Jim Jarmusch, 1986. Starring: Tom Waits, John Lurie, Roberto Benigni, Ellen Barkin. Cult.

"I am no criminal. I am a good egg. We are. We are a good egg."

—With this, the bouncing Roberto Benigni's "Bob" brings his two new friends together in Jim

Jarmusch's 1986 prison break film Down by Law.

Those familiar with Jim Jarmusch's films have come to expect and embrace the notion of the outsider. His characters, square pegs in round holes, consistently defy their societal norms and expectations. As defined and complex as their interests and personalities are, they are immanent sojourners in search of a secure homeland. From the black samurai hit man in Ghost Dog to the foreign tourists visiting Memphis in Mystery Train to the hunted accountant in Dead Man, Jarmusch's films are about opposites and reversals; characters who don't belong, awkwardly trying to find their place. Jarmusch consistently mines great comedy in these situations, particularly when it comes to race. One need look no further than Coffee and Cigarettes to find Bill Murray getting health tips in a diner from Wu Tang's RZA and GZA. Even with his more dramatic work (i.e., Stranger than Paradise, Broken Flowers, The Limits of Control), Jarmusch continues to explore and relate to the transients of society. In Down by Law, we are introduced to three such characters.

The film, shot gorgeously in black and white, opens with an introductory prologue. A shot of a graveyard takes off into moving shots of New Orleans. We drift along the streets of the city, taking in the beautifully decaying architecture and landscape with Tom Waits's Jockey Full of Bourbon playing underneath.The film, set in the city's present day, paints New Orleans as a ghost town. Characters loiter on different streets with nary a passerby or car in sight. With the ghostly starkness of black and white and the absence of extraneous city noises, the overall mood is reminiscent of a 1940's noir film. Besides the modern cars, the film looks timeless, or at the very least older than its 25 years.

Following the opening, we are introduced first to Jack (played by artist/musician John Lurie). He wakes up next to a woman and heads to the porch to check on another. He is their pimp. Across town, Zack (played by musician Tom Waits) walks into his room and sneaks into bed next to his girlfriend, Laurette (played by Ellen Barkin). Jarmusch jumps back and forth between the two men, mirroring their similarly aimless lives. Zack, a radio DJ, is violently thrown out by his girlfriend Laurette. As she berates him for not loving her and messing up his career, Zack looks away stoically. He is passive, apathetic. Her attempts to incite a passionate response from him are met with disregard. Afterwards, he picks up his belongings in the street that Laurette had thrown out and sits in the gutter. Meanwhile, Jack's home life mirrors Zack's. When one of his girls, Bobbie (played by Billie Neal), criticizes him for not being ambitious enough, he takes it in stride. Complaining he won't get violent with her for her insubordination, she too seeks to incite a passionate response. Both characters, lost in their careers and love, are kindred spirits cut from the same cloth. One, the businessman, one, the artist. These are not back-alley, seedy lowlifes, however. Jarmusch clearly loves his characters and endears them to us early on.

When both are separately propositioned and set up for bad business deals, they are arrested and end up in Orleans Parish Prison. Here the film leaves the hard-boiled, sequestered streets of New Orleans and becomes a fabled odyssey as Jack and Zack's stories become linked. Now cell mates, they struggle to get along until they are joined by Bob, played by Italian comic actor Roberto Benigni. Bob barely speaks English, but that doesn't stop him from engaging Jack and Zack in incessant conversation. He soon becomes a bridge for the two men to get along, alleviating their shared tension with his brand of cartoonish humor. When he plans an escape, the two follow suit and eventually flee into the Louisiana swamp. At first, they are clearly pursued. Sirens and the barking of dogs blare in the distance. Once they make some distance from the prison however, they are once again adrift, lost in the wilderness.

Down by Law, like Jarmusch's other work, is an instinctively emotional film. His shots are always wide, allowing the characters to breath, live, and exist in the space. Jarmusch takes time to sit with his characters. With 121 cuts throughout the film, each shot ends up averaging 48 seconds in length. This makes for a slow, prodding plot when compared with other "prison" films. But in Down by Law, with its rich, crisp black and white picture and deep focused lenses, Jarmusch gives us a chance to observe his characters; to find the details in and around their space and digest the emotion of the scene. There is very much a stage theatrical quality to the experience. Instead of feeling slow, the film is visually striking and vivid with understated detail (both in the picture and performances), requiring our concentrated attention. And although the film (focused on three lost drifters) effectuates a feeling of loneliness and meandering, it is in fact rather sparse, moving quite economically through the plot, each scene succinctly building upon the last. No shot feels wasted or superfluous.

The end result is a fable of sorts. Three strangers, adrift in New Orleans and linked together by a common past and way of living, are brought together by unfortunate circumstances. As each pursues something they have not yet attained, we sympathize with their plight, rooting not for them to come together as a team, nor for their escape and subsequent freedom. Rather, we root for them to attain the same goal we want for ourselves: To find our place, our peace of mind in this sad and beautiful world.

—With this, the bouncing Roberto Benigni's "Bob" brings his two new friends together in Jim

Jarmusch's 1986 prison break film Down by Law.

Those familiar with Jim Jarmusch's films have come to expect and embrace the notion of the outsider. His characters, square pegs in round holes, consistently defy their societal norms and expectations. As defined and complex as their interests and personalities are, they are immanent sojourners in search of a secure homeland. From the black samurai hit man in Ghost Dog to the foreign tourists visiting Memphis in Mystery Train to the hunted accountant in Dead Man, Jarmusch's films are about opposites and reversals; characters who don't belong, awkwardly trying to find their place. Jarmusch consistently mines great comedy in these situations, particularly when it comes to race. One need look no further than Coffee and Cigarettes to find Bill Murray getting health tips in a diner from Wu Tang's RZA and GZA. Even with his more dramatic work (i.e., Stranger than Paradise, Broken Flowers, The Limits of Control), Jarmusch continues to explore and relate to the transients of society. In Down by Law, we are introduced to three such characters.

The film, shot gorgeously in black and white, opens with an introductory prologue. A shot of a graveyard takes off into moving shots of New Orleans. We drift along the streets of the city, taking in the beautifully decaying architecture and landscape with Tom Waits's Jockey Full of Bourbon playing underneath.The film, set in the city's present day, paints New Orleans as a ghost town. Characters loiter on different streets with nary a passerby or car in sight. With the ghostly starkness of black and white and the absence of extraneous city noises, the overall mood is reminiscent of a 1940's noir film. Besides the modern cars, the film looks timeless, or at the very least older than its 25 years.

Following the opening, we are introduced first to Jack (played by artist/musician John Lurie). He wakes up next to a woman and heads to the porch to check on another. He is their pimp. Across town, Zack (played by musician Tom Waits) walks into his room and sneaks into bed next to his girlfriend, Laurette (played by Ellen Barkin). Jarmusch jumps back and forth between the two men, mirroring their similarly aimless lives. Zack, a radio DJ, is violently thrown out by his girlfriend Laurette. As she berates him for not loving her and messing up his career, Zack looks away stoically. He is passive, apathetic. Her attempts to incite a passionate response from him are met with disregard. Afterwards, he picks up his belongings in the street that Laurette had thrown out and sits in the gutter. Meanwhile, Jack's home life mirrors Zack's. When one of his girls, Bobbie (played by Billie Neal), criticizes him for not being ambitious enough, he takes it in stride. Complaining he won't get violent with her for her insubordination, she too seeks to incite a passionate response. Both characters, lost in their careers and love, are kindred spirits cut from the same cloth. One, the businessman, one, the artist. These are not back-alley, seedy lowlifes, however. Jarmusch clearly loves his characters and endears them to us early on.

When both are separately propositioned and set up for bad business deals, they are arrested and end up in Orleans Parish Prison. Here the film leaves the hard-boiled, sequestered streets of New Orleans and becomes a fabled odyssey as Jack and Zack's stories become linked. Now cell mates, they struggle to get along until they are joined by Bob, played by Italian comic actor Roberto Benigni. Bob barely speaks English, but that doesn't stop him from engaging Jack and Zack in incessant conversation. He soon becomes a bridge for the two men to get along, alleviating their shared tension with his brand of cartoonish humor. When he plans an escape, the two follow suit and eventually flee into the Louisiana swamp. At first, they are clearly pursued. Sirens and the barking of dogs blare in the distance. Once they make some distance from the prison however, they are once again adrift, lost in the wilderness.

Down by Law, like Jarmusch's other work, is an instinctively emotional film. His shots are always wide, allowing the characters to breath, live, and exist in the space. Jarmusch takes time to sit with his characters. With 121 cuts throughout the film, each shot ends up averaging 48 seconds in length. This makes for a slow, prodding plot when compared with other "prison" films. But in Down by Law, with its rich, crisp black and white picture and deep focused lenses, Jarmusch gives us a chance to observe his characters; to find the details in and around their space and digest the emotion of the scene. There is very much a stage theatrical quality to the experience. Instead of feeling slow, the film is visually striking and vivid with understated detail (both in the picture and performances), requiring our concentrated attention. And although the film (focused on three lost drifters) effectuates a feeling of loneliness and meandering, it is in fact rather sparse, moving quite economically through the plot, each scene succinctly building upon the last. No shot feels wasted or superfluous.

The end result is a fable of sorts. Three strangers, adrift in New Orleans and linked together by a common past and way of living, are brought together by unfortunate circumstances. As each pursues something they have not yet attained, we sympathize with their plight, rooting not for them to come together as a team, nor for their escape and subsequent freedom. Rather, we root for them to attain the same goal we want for ourselves: To find our place, our peace of mind in this sad and beautiful world.

Posted by:

Robbie Ikegami

Dec 20, 2011 11:45pm