Movies We Like

Who Framed Roger Rabbit

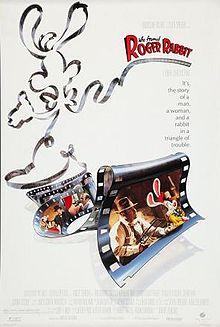

Dir: Robert Zemeckis, 1988. Starring: Bob Hoskins, Christopher Lloyd, Joanna Cassidy. Children's.

"The problem is I got a fifty-year-old lust and three-year-old dinky."

—Baby Herman's irreverent response to being labeled a ladies' man pushes the envelope of cartoon decency in Disney's groundbreaking film from 1988.

Who Framed Roger Rabbit, Robert Zemeckis's noir/fantasy/crime/comedy/animation is a complicated one to boil down. In large part, it is an homage to the classic film noir genre with the archetypal down-and-out private eye (scarred by a troubled past) trying to solve a crime and, ultimately, redeem himself. In another sense, it is a fully animated film, with over 50 minutes of complicated animation filling the screen. The two worlds are brought together through breathtaking special effects in this strikingly original and innovative vision.

The film opens with a Looney Tunes-style cartoon, complete with character-introducing title cards. Roger Rabbit, a short, white, red overall-wearing rabbit is left to babysit Baby Herman who is filled with a tenacious desire to retrieve the cookie jar atop the refrigerator. When Roger finds Baby Herman scaling the counter, he tries to rescue him only to get tripped up by various items around the house. Unwittingly, the baby forges on to his goal as Roger's feeble attempts end in slap-sticky results. At the climactic moment, the refrigerator lands emphatically on Roger's head. The door swings open revealing Roger smiling senselessly as a small halo of blue birds tweet around his head. Almost immediately, a loud, aggravated voice interrupts with the word "cut" and the camera moves backward revealing a physical kitchen set as human crew members scramble to reset the stage. The human director berates Roger for messing up his lines. He was supposed to see stars, not birds. To further draw the contrast between the reality and illusion, Baby Herman, in a coarse masculine voice storms off the sound stage demanding his cigar and looking up the skirt of a female crew member. The camera continues to track backward as a graveling Roger follows the director until it stops at human detective Eddie Valiant (played by Bob Hoskins). "Toons," he mutters in disdain to himself as the opening scene (effectively introducing us to the world) comes to a close.

In the early 1980s, animation was on its last breath. With a string of mediocre and largely panned animated films such as The Black Cauldron and The Great Mouse Detective, Disney seemed to be closing the chapter on the medium which they had pioneered for so long. In the midst of the decline, Roy Disney (the nephew of founder Walt) fought desperately to keep the animation department intact against pressure from newcomers Michael Eisner and Jeffrey Katzenberg and their plans to shut down the department to focus solely on live-action films. With the old guard pitted against the new, it would take a compromise from all sides to invest in a project that would serve as a gauge for the profitability of Disney animation. And since the divide centered on animation versus live-action, it was fitting that the project be a hybrid of both mediums. Gary K. Wolf's 1981 novel Who Censored Roger Rabbit? was optioned by Disney soon after its release and featured a world where comic strip characters lived and interacted with humans. Because it was Disney, it seemed only natural to adapt the concept using their trove of animated characters. Bringing in Steven Spielberg and his cohorts at Amblin as co-producers, Disney green-lit Who Framed Roger Rabbit with a 30 million dollar budget, the most expensive animated budget to that point. The stakes had now been raised for Disney's gamble to revamp the medium. Still without a director, Disney made several offers to various names around town. Only years prior, after the book had been optioned, a young director expressed interest in the project, but due to some disappointing early films, Disney passed on his services. Not until after the success of his 1985 blockbuster Back to the Future, did Disney reconsider and subsequently hire Robert Zemeckis to direct the film. Hiring animator Richard Williams to direct the animated sequences, the pieces were finally in place for production.

Robert Zemeckis's vision for Who Framed Roger Rabbit was to shoot a film as if it were purely live action, with the yet-to-be-drawn animated characters treated as if they were human actors. The result feels more live action than cartoon, with a seamless blend of animated characters inhabiting the space. During production, painstaking preparations were made to create the illusion. Using robotics and puppetry, props and set pieces moved by themselves, creating the template over which the animators would paint. During shooting, a prop gun moves through the air suspended by fishing line. Chairs and other objects move on their own through remote control. When the animation is added, the finished product looks incredible and those small touches of the cartoons' physical interactions with the real world make the entire illusion work. Adding to the realism, the perspective of the animated characters subtly move and change in sync with the actors. This was a breaking of the unwritten rule that the camera was to always be static in animation. To create this illusion, animators working in San Francisco, Los Angeles, and England spent an entire year drawing and painting the characters in each frame of film. Before the availability of computers, each character would be hand drawn over a printout of the film frame. When ready, optical printers would photograph the animation onto the film, combining the two elements. To give an added richness to the animation, multiple layers were drawn for the characters that would include layers for lighting and shadows. This further integrated them into the real world by giving a more three dimensional quality. The result is a serene blend of cartoon and humans that is absolutely believable. At the core of this mix is the largely pantomime performance of Bob Hoskins. His constant physical and relational struggle with Roger Rabbit is remarkable. Because Hoskins believes that Roger Rabbit exists in front of him, so do we.

Who Framed Roger Rabbit went through numerous drafts and plot changes in its adaptation. The finalized plot centers around the real-life conspiracy theory of automakers' attempt to sabotage public transit in Los Angeles in order to sell more cars. The striking similarity to Polanski's Chinatown is due to the writers lifting the plot from the abandoned third installment to the Chinatown franchise. And while the film is mainly a special effects feat, the story stays true to the convoluted plots of classic detective stories. Combined with the adult themes and sexual innuendos and characters (particularly Jessica Rabbit), it's surprisingly mature. Murder, quasi-adultery, and alcoholism abound in the film, serving, in retrospect, as an artifact of the 1980s, which produced much more darker themes in their children's stories than today. It's because of this mature portrayal of the world (itself a commitment to the staples of the noir genre) that make the contrast of involving children's icons so compelling. A child might (rightly so) be confused by a cartoon murdering a human. But with Disney set on scrapping animation altogether, it makes sense how they would be willing to pull the curtain back on the entire illusion just to shake things up. In addition to the perpetuation of crime genre themes, Roger Rabbit's set design of 1940's Los Angeles is beautiful, but much more romanticized than the grittiness of classic noir. Longtime Zemeckis collaborator Alan Silvestri scores the film complementing the theme with a mixture of jazz and cartoonish overtures.

Upon its release, Who Framed Roger Rabbit was widely acclaimed critically and commercially, with a special Academy Award given for achievement in special effects. Disney's gamble had paid off immensely and in more ways than one saved not only Disney animation, but hand-drawn animation for the next 10 years, paving the way for computer animated films. Beginning with 1989's The Little Mermaid, Disney experienced what became known as their "renaissance," built on a string of successful animated films based on both classic and new fairy tales alike. Meanwhile, Roger Rabbit's popularity persisted beyond the 1980s. In 1993, Disneyland opened "Toontown," a cartoonish-themed area inspired by the film, featuring a Roger Rabbit-themed ride. And several short cartoons featuring Roger Rabbit and Baby Herman were played before the screenings of Disney live- action films. Aside from viewing it as simply a Disney film though, Who Framed Roger Rabbit is truly an original, visionary film with impressive, practical special effects and animation. Like Ridley Scott's Blade Runner (also a film noir fantasy hybrid), Who Framed Roger Rabbit employs those special effects to create a visually unique, complex, and striking world. It romantically pays tribute to the annals of hand-drawn animation created by Disney, Warner Bros., Tex Avery, et al., all the while offering something fresh and original. In the current digital age, the film is a nostalgic relic of past special effects ingenuity. Even more so, it was one of those rare instances, seldom seen today, where a big studio took a big gamble on a fantastic and original vision to create something equally special.

____________________________

Who Framed Roger Rabbit was nominated for seven Oscars including Best Art Direction, Best Cinematography, and Best Sound, and won for Best Film Editing, Best Sound Effects Editing, Best Visual Effects, and a Special Achievement Award to Richard Williams for animation direction and creation of cartoon characters.

—Baby Herman's irreverent response to being labeled a ladies' man pushes the envelope of cartoon decency in Disney's groundbreaking film from 1988.

Who Framed Roger Rabbit, Robert Zemeckis's noir/fantasy/crime/comedy/animation is a complicated one to boil down. In large part, it is an homage to the classic film noir genre with the archetypal down-and-out private eye (scarred by a troubled past) trying to solve a crime and, ultimately, redeem himself. In another sense, it is a fully animated film, with over 50 minutes of complicated animation filling the screen. The two worlds are brought together through breathtaking special effects in this strikingly original and innovative vision.

The film opens with a Looney Tunes-style cartoon, complete with character-introducing title cards. Roger Rabbit, a short, white, red overall-wearing rabbit is left to babysit Baby Herman who is filled with a tenacious desire to retrieve the cookie jar atop the refrigerator. When Roger finds Baby Herman scaling the counter, he tries to rescue him only to get tripped up by various items around the house. Unwittingly, the baby forges on to his goal as Roger's feeble attempts end in slap-sticky results. At the climactic moment, the refrigerator lands emphatically on Roger's head. The door swings open revealing Roger smiling senselessly as a small halo of blue birds tweet around his head. Almost immediately, a loud, aggravated voice interrupts with the word "cut" and the camera moves backward revealing a physical kitchen set as human crew members scramble to reset the stage. The human director berates Roger for messing up his lines. He was supposed to see stars, not birds. To further draw the contrast between the reality and illusion, Baby Herman, in a coarse masculine voice storms off the sound stage demanding his cigar and looking up the skirt of a female crew member. The camera continues to track backward as a graveling Roger follows the director until it stops at human detective Eddie Valiant (played by Bob Hoskins). "Toons," he mutters in disdain to himself as the opening scene (effectively introducing us to the world) comes to a close.

In the early 1980s, animation was on its last breath. With a string of mediocre and largely panned animated films such as The Black Cauldron and The Great Mouse Detective, Disney seemed to be closing the chapter on the medium which they had pioneered for so long. In the midst of the decline, Roy Disney (the nephew of founder Walt) fought desperately to keep the animation department intact against pressure from newcomers Michael Eisner and Jeffrey Katzenberg and their plans to shut down the department to focus solely on live-action films. With the old guard pitted against the new, it would take a compromise from all sides to invest in a project that would serve as a gauge for the profitability of Disney animation. And since the divide centered on animation versus live-action, it was fitting that the project be a hybrid of both mediums. Gary K. Wolf's 1981 novel Who Censored Roger Rabbit? was optioned by Disney soon after its release and featured a world where comic strip characters lived and interacted with humans. Because it was Disney, it seemed only natural to adapt the concept using their trove of animated characters. Bringing in Steven Spielberg and his cohorts at Amblin as co-producers, Disney green-lit Who Framed Roger Rabbit with a 30 million dollar budget, the most expensive animated budget to that point. The stakes had now been raised for Disney's gamble to revamp the medium. Still without a director, Disney made several offers to various names around town. Only years prior, after the book had been optioned, a young director expressed interest in the project, but due to some disappointing early films, Disney passed on his services. Not until after the success of his 1985 blockbuster Back to the Future, did Disney reconsider and subsequently hire Robert Zemeckis to direct the film. Hiring animator Richard Williams to direct the animated sequences, the pieces were finally in place for production.

Robert Zemeckis's vision for Who Framed Roger Rabbit was to shoot a film as if it were purely live action, with the yet-to-be-drawn animated characters treated as if they were human actors. The result feels more live action than cartoon, with a seamless blend of animated characters inhabiting the space. During production, painstaking preparations were made to create the illusion. Using robotics and puppetry, props and set pieces moved by themselves, creating the template over which the animators would paint. During shooting, a prop gun moves through the air suspended by fishing line. Chairs and other objects move on their own through remote control. When the animation is added, the finished product looks incredible and those small touches of the cartoons' physical interactions with the real world make the entire illusion work. Adding to the realism, the perspective of the animated characters subtly move and change in sync with the actors. This was a breaking of the unwritten rule that the camera was to always be static in animation. To create this illusion, animators working in San Francisco, Los Angeles, and England spent an entire year drawing and painting the characters in each frame of film. Before the availability of computers, each character would be hand drawn over a printout of the film frame. When ready, optical printers would photograph the animation onto the film, combining the two elements. To give an added richness to the animation, multiple layers were drawn for the characters that would include layers for lighting and shadows. This further integrated them into the real world by giving a more three dimensional quality. The result is a serene blend of cartoon and humans that is absolutely believable. At the core of this mix is the largely pantomime performance of Bob Hoskins. His constant physical and relational struggle with Roger Rabbit is remarkable. Because Hoskins believes that Roger Rabbit exists in front of him, so do we.

Who Framed Roger Rabbit went through numerous drafts and plot changes in its adaptation. The finalized plot centers around the real-life conspiracy theory of automakers' attempt to sabotage public transit in Los Angeles in order to sell more cars. The striking similarity to Polanski's Chinatown is due to the writers lifting the plot from the abandoned third installment to the Chinatown franchise. And while the film is mainly a special effects feat, the story stays true to the convoluted plots of classic detective stories. Combined with the adult themes and sexual innuendos and characters (particularly Jessica Rabbit), it's surprisingly mature. Murder, quasi-adultery, and alcoholism abound in the film, serving, in retrospect, as an artifact of the 1980s, which produced much more darker themes in their children's stories than today. It's because of this mature portrayal of the world (itself a commitment to the staples of the noir genre) that make the contrast of involving children's icons so compelling. A child might (rightly so) be confused by a cartoon murdering a human. But with Disney set on scrapping animation altogether, it makes sense how they would be willing to pull the curtain back on the entire illusion just to shake things up. In addition to the perpetuation of crime genre themes, Roger Rabbit's set design of 1940's Los Angeles is beautiful, but much more romanticized than the grittiness of classic noir. Longtime Zemeckis collaborator Alan Silvestri scores the film complementing the theme with a mixture of jazz and cartoonish overtures.

Upon its release, Who Framed Roger Rabbit was widely acclaimed critically and commercially, with a special Academy Award given for achievement in special effects. Disney's gamble had paid off immensely and in more ways than one saved not only Disney animation, but hand-drawn animation for the next 10 years, paving the way for computer animated films. Beginning with 1989's The Little Mermaid, Disney experienced what became known as their "renaissance," built on a string of successful animated films based on both classic and new fairy tales alike. Meanwhile, Roger Rabbit's popularity persisted beyond the 1980s. In 1993, Disneyland opened "Toontown," a cartoonish-themed area inspired by the film, featuring a Roger Rabbit-themed ride. And several short cartoons featuring Roger Rabbit and Baby Herman were played before the screenings of Disney live- action films. Aside from viewing it as simply a Disney film though, Who Framed Roger Rabbit is truly an original, visionary film with impressive, practical special effects and animation. Like Ridley Scott's Blade Runner (also a film noir fantasy hybrid), Who Framed Roger Rabbit employs those special effects to create a visually unique, complex, and striking world. It romantically pays tribute to the annals of hand-drawn animation created by Disney, Warner Bros., Tex Avery, et al., all the while offering something fresh and original. In the current digital age, the film is a nostalgic relic of past special effects ingenuity. Even more so, it was one of those rare instances, seldom seen today, where a big studio took a big gamble on a fantastic and original vision to create something equally special.

____________________________

Who Framed Roger Rabbit was nominated for seven Oscars including Best Art Direction, Best Cinematography, and Best Sound, and won for Best Film Editing, Best Sound Effects Editing, Best Visual Effects, and a Special Achievement Award to Richard Williams for animation direction and creation of cartoon characters.

Posted by:

Robbie Ikegami

Jan 18, 2012 6:56pm