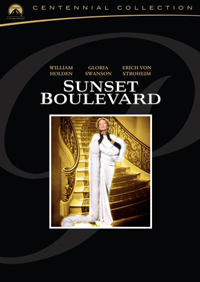

Sunset Blvd.

There has never been a screenplay quite like Charles Brackett and director Billy Wilder’s screenplay for their 1950 opus Sunset Blvd. It’s a macabre gothic noir comedy about the ghosts of Hollywood past. It’s one of those films, though a first-string classic, where the myths and back-stage stories are just as memorable as the film itself. For a legendary cynic like Wilder it was his ultimate drubbing of the hand that fed him. For star Gloria Swanson it was the ultimate film comeback (ten times more unlikely than, say, Travolta in Pulp Fiction). And for her co-star William Holden it began a decade of big performances in important films that cemented him as a major actor. In a time when the studios controlled their products as well as their own image with an iron fist, it’s shocking that Sunset Blvd. ever got made.

There has never been a screenplay quite like Charles Brackett and director Billy Wilder’s screenplay for their 1950 opus Sunset Blvd. It’s a macabre gothic noir comedy about the ghosts of Hollywood past. It’s one of those films, though a first-string classic, where the myths and back-stage stories are just as memorable as the film itself. For a legendary cynic like Wilder it was his ultimate drubbing of the hand that fed him. For star Gloria Swanson it was the ultimate film comeback (ten times more unlikely than, say, Travolta in Pulp Fiction). And for her co-star William Holden it began a decade of big performances in important films that cemented him as a major actor. In a time when the studios controlled their products as well as their own image with an iron fist, it’s shocking that Sunset Blvd. ever got made.

Narrating from a swimming pool of a rundown mansion, a floating corpse tells his story of how he ended up there. Down-and-out screenwriter Joe Gillis (Holden) can’t land a new assignment and is on the run from debt collectors. With a flat tire he hides his car in the garage of that rundown mansion. Invited in by the home’s butler, Max (Erich von Stroheim), to lend a hand for the funeral of a monkey Joe soon meets the mistress of the house, one-time silent film star, Norma Desmond (Swanson). She lives with only one foot in reality. Her decrepit house is filled with photos and mementos of her former self from her glory days 30 years earlier. Eventually she employs Joe to write her gaudy screenplay that she plans to use as a comeback vehicle. Joe also takes on the role of gigolo, becoming her lover as she keeps him dressed in tuxes and fancy gold watches.

Out of the Past

Of that post-WWII generation of male actors who came of age in war flicks but really defined themselves in the Film Noir genre, none was cooler than Robert Mitchum (and that was a group of cool dudes that included Burt Lancaster, Richard Widmark, Sterling Hayden, Robert Ryan, and his co-star here Kirk Douglas). Whether playing a hero or a villain, Mitchum reeked of both danger and manly charm even when he spewed indifference. His career spanned decades with a number of signature roles and important films, but of the Noir period none was better than that of ex-detective turned gas station owner Jeff Bailey in Out of the Past.

Director Jacques Tourneur is more known today for his groundbreaking horror flicks with producer Val Lewton: Cat People, The Leopard Man and I Walked With a Zombie. Though in retrospect those eerie and strange shadowy black n’ white flicks could be called horror noir, making the Frenchman the perfect director to bring his almost Expressionistic approach to a crime mystery in what was then considered a B-genre. Like much gothic horror, Jeff Bailey is a guy haunted by his past, trying to escape from his own mind and hide from his own instincts.

Continue ReadingThe Maltese Falcon

Like John Ford & John Wayne or Scorsese & De Niro, John Huston & Humphrey Bogart's work together as director and star will be forever linked in audiences' subconscious. After years of being a happening screenwriter, Huston got his chance to direct his own adaptation of Dashiell Hammett's crime novel, The Maltese Falcon. The film would help make Bogart a leading man, would lead to a 50-year career for Huston, and set the standard for detective films to come.

Like many detective and crime films of the 1940s, The Maltese Falcon is often improperly lumped in with the Film Noir genre. At best, The Maltese Falcon could be deemed a kick-starter to the genre that actually peaked in the post-WWII years. With the exception of a femme fatale or a detective it has little in common stylistically with the best of Film Noir (The Postman Always Rings Twice, Out Of The Past, etc.). That's not to say that the film (and the book) were not hugely influential, they were.

Continue ReadingDetour (1945)

Film students across the world come to be familiar with Edgar G. Ulmer's Detour because it's one of the first examples of the "noir" genre; it makes clever use of its low budget and it offers a classic, if simplistic, story on how men and women can manipulate each other into horrendous actions. While all of these are the reasons why the film still holds up today, it's also more fun to think of Detour as the 1940s equivalent of Stranger Than Paradise or Clerks. Super low-budget and completely pioneering in its time for depicting human behavior, this is a film that can still prove to people that quality films can be made outside of Hollywood.

The story opens up on a grizzled and paranoid-looking Al Roberts, who staggers into a diner somewhere in the barren remoteness of Southern California, just outside of Los Angeles. He reacts harshly when somebody in the diner plays a particular song on the jukebox and, after apologizing and being nearly kicked out, he drinks his coffee and begins to tell his story over narration.

Continue ReadingDouble Indemnity

If you know nothing about film noir, start with Double Indemnity. This classic by director Billy Wilder was among the first bona fide pictures in the postwar genre, and it contains all the essential elements – lust, greed, violence, betrayal – that animated this wondrous American style during its great epoch of the 1940s and ‘50s.

Based on a novel by hardboiled fiction forefather James M. Cain, the biting script was co-authored by Wilder and Raymond Chandler, creator of detective Philip Marlowe. The brutal, sleazy tale is recounted (in traditional voiceover style) by canny but weak-willed Los Angeles insurance salesman Walter Neff (Fred MacMurray), who is ensnared by the scheming trollop Phyllis Dietrichson (Barbara Stanwyck). The pair hatch a complicated plot to murder her wealthy husband and collect a large double indemnity insurance policy. But they don’t reckon on the acute intuition of Neff’s friend and co-worker, claims investigator Barton Keyes (Edward G. Robinson), whose “little man” in the pit of his stomach tells him something isn’t quite right.

Continue ReadingAce In The Hole

Though it doesn’t revolve around a murder or a heist, Ace in the Hole remains a definitive film noir. Bitter, caustic, and unremittingly dark, it prophesied our age of journalistic madness as it focused on a literal “media circus” developed by a story-hungry press.

In a virtuoso performance that equals his turn in Vincente Minnelli’s The Bad and the Beautiful, Kirk Douglas stars as Chuck Tatum, a down-on-his-heels newsman who desperately takes a job at a tank-town Albuquerque paper. He stumbles on the headline of a lifetime after the owner of a roadside diner is trapped in an abandoned mineshaft while hunting for Indian artifacts. Envisioning a Pulitzer Prize and a return to the big time in New York, Tatum ruthlessly controls the story, befriending the terrified victim (Richard Benedict), romancing his slatternly wife (Jan Sterling), and cynically working local authorities and big-city editors. Then things start to come apart…

Continue Reading