Movies We Like

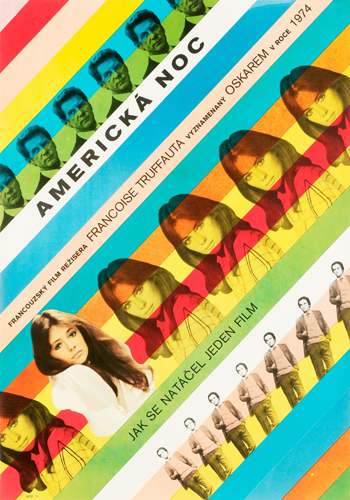

Day for Night

Dir: Francois Truffaut, 1973. Starring: Jacqueline Bisset, Jean-Pierre Leaud, Francois Truffaut. Foreign. Language: French, English.

"We meet, we work together, we love each other, and then...pfft...as soon as we grasp something, it's gone."

— The aging actress Severine’s (played by Italian starlet Valentia Cortese) astute lament on the intangible nature of filmmaking resounds the yearning romance of all art in Francois Truffaut’s 1973 film, Day for Night.

The title, La nuit américaine (literally: The American Night), refers to the process of filtering the camera to shoot a scene during the day to look as if it is, in fact, night. Known in America as Day for Night, the film centers around the shooting of a film entitled Je vous presente Pamela (Meet Pamela), a dramatic tragedy in which a young French wife falls in love with her husband’s father. Day for Night pays minimal attention to the film within itself however, and instead follows the cast and crew as they struggle through both the physical production as well as a flurry of interpersonal conflicts.

By now, ‘the film within a film’ plotline has been thoroughly exhausted. But Day for Night remains one of the best of its genre and definitely the most celebratory. Allusions to Fellini’s 8 1/2 are certainly inevitable. However, a director struggling with the personalities of cast and crew to create his vision are maybe the only shared elements of the two stories. While Fellini’s seamless marriage between dream and reality reflects his own cinematic philosophy, that film is a dream, Truffaut becomes the documentarian, exposing and mirroring his own life to the point of playing the part of Meet Pamela’s director. But he is a propagandist. He seeks to seduce us in the way he himself was seduced by cinema. To Truffaut, film is not a dream as Fellini expressed, nor an agent for social change as his contemporary-cum-rival Jean-Luc Godard staunchly maintains. For him, it is a woman. And like Alphonse (played by Jean-Pierre Leaud) in Day for Night discovers, woman is magic, and also, she isn’t. Film, like woman, is an enigma, a temptress, a lover.

This unrequited attainment of woman as a concept marks Truffaut’s entire body of work. From his early short, Les Mistons, about the pre-pubescent puppy love a group of kids share for an older woman, to the entire Antoine Doinel series, which placed Truffaut’s representative (Leaud) in and out of the arms of women he could not keep, Truffaut’s filmic pursuit of women haunts his best work and is absent from his worst. For more proof, see Mississippi Mermaid, The Soft Skin, The Woman Next Door,The Man Who Loved Women, and Jules and Jim. Even the titles of these films evoke the wistful courtship of the feminine mystique.

In Day for Night, he blends his two loves. Ever the romantic, Truffaut brings us into his passionate affair with cinema. Curiously though, it is not the flickering fantasy of the darkened room that he invites us to—that communal experience we all share when the lights dim and pictures flash before our eyes—but rather, the gritty nuts and bolts of the movie machine. He loves not the product of cinema alone, but the process through which it is made—the war to create. And yet, he shirks a cinéma vérité documentary style with handheld cameras and natural light. The reality of the illusion is instead glamorized and polished, as Truffaut employs an array of filmic effects: jump cuts, freeze frames, black and white, and voice-over. At certain times, the camera is hand-held, at others it’s on a tripod or gliding on a dolly track, crane, or even helicopter. Truffaut’s lust for filmmaking drips onto the film, treating the camera, rolling film strips, props, etc. as if they were legs and breasts—body parts to be admired with dreamlike quality. In fact, the light throughout is soft and filled in every space; the color, warm and familial. Georges Delerue’s score wonderfully mirrors the blend of the technical and the artistic with a rigid pomp and circumstance sung by choral strings and French horns. Montages occur throughout the film, flowing through the set, illuminating everything and everyone involved. At the end of one such ‘love scene,' the camera, seen from above, ascends into the sky on a crane. Upon reaching its apex, the camera tilts and pans around, shooting directly into our camera, our eyes, at us. How much more can Truffaut pull us into this love affair?

Beneath the bleeding romance of Day for Night, however, resides a deeper, more profound theme: the dichotomy of illusion and reality. Here, the dividing line is drawn at the first scene. The film opens with a scene from Meet Pamela (the illusion) when it is abruptly stopped by Truffaut himself, emphatically yelling “cut” and thrusting us into Day for Night (reality, at least, the reality of Day for Night). With the curtain now drawn, Truffaut invites us into the filmmaker’s world. We become part of the crew. The camera, almost always at eye level with its subject is empathetic to the characters. We are in this romance with them. This wonderful tour, led by Truffaut himself as the director Ferrand, guides us through the beautiful illusion with its equally beautiful and even more exciting reality. As the drama of Meet Pamela (illusion) is meticulously fabricated, an unpredictable soap opera (reality) unfolds behind the camera. Truffaut shows us both sides, acting himself as the mirror between reality and reflection.

This theme of illusion and reality permeates the film. When it is discovered an actress is pregnant (reality), the producer attempts to fit it into the film (illusion) before Ferrand (Truffaut) rejects it as a disruption to the rest of the illusion. When Severine (Cortese) stumbles through an emotional scene, opening the wrong door again and again, one of the crew reveals to another that her son has leukemia. Her reality belies the drama of the illusion and she is unable to bear the charade. When the veteran actor Alexandre (Jean-Pierre Aumont), with a reputation for being a ladies’ man (illusion), arrives at the airport to pick up his friend, he greets a young man who in fact turns out to be his lover (reality). Truffaut continues to break down the walls of illusion between the film and the film within. A late night conversation with an actress becomes the next day’s rewritten lines. The plot of Day for Night slowly begins to mirror the plot of Meet Pamela. The actors, who are playing actors, recite lines of reciting lines. At one point, Leaud’s character sits in a theater watching his dailies, mouthing the lines along with his onscreen self. One can imagine Leaud sitting in a theater in France, watching himself on a screen watch himself on a screen, each one mouthing the actor's lines. In fact, with the exception of Alexandre, all of the actors at some point gaze into their reflection in the mirror. On one level, Truffaut is pushing the actors to play themselves as he seeks to blend the illusion (Meet Pamela) with the other illusion (Day for Night) and ultimately, with reality. Throughout all this, Truffaut is the painstaking orchestrator, consumed in his creation. A firm believer in the idea and role of the auteur, he places his most personal, most convicted, and most passionate stamp on Day for Night.

In Truffaut’s loving reverence of film, it is king. But, it is not reality. Film is not life at 24 frames per second. The real drama of life exists not on screen, but is only augmented by it. Like all significant art, film is the mirror through which we can see and understand our own humanity. Inferior to reality? Yes. Unnecessary to it? No. After all, it’s in our nature, as Truffaut’s Ferrand observes: "People used to stare at fires, now they watch TV. We need to see moving images, especially after dinner."

— The aging actress Severine’s (played by Italian starlet Valentia Cortese) astute lament on the intangible nature of filmmaking resounds the yearning romance of all art in Francois Truffaut’s 1973 film, Day for Night.

The title, La nuit américaine (literally: The American Night), refers to the process of filtering the camera to shoot a scene during the day to look as if it is, in fact, night. Known in America as Day for Night, the film centers around the shooting of a film entitled Je vous presente Pamela (Meet Pamela), a dramatic tragedy in which a young French wife falls in love with her husband’s father. Day for Night pays minimal attention to the film within itself however, and instead follows the cast and crew as they struggle through both the physical production as well as a flurry of interpersonal conflicts.

By now, ‘the film within a film’ plotline has been thoroughly exhausted. But Day for Night remains one of the best of its genre and definitely the most celebratory. Allusions to Fellini’s 8 1/2 are certainly inevitable. However, a director struggling with the personalities of cast and crew to create his vision are maybe the only shared elements of the two stories. While Fellini’s seamless marriage between dream and reality reflects his own cinematic philosophy, that film is a dream, Truffaut becomes the documentarian, exposing and mirroring his own life to the point of playing the part of Meet Pamela’s director. But he is a propagandist. He seeks to seduce us in the way he himself was seduced by cinema. To Truffaut, film is not a dream as Fellini expressed, nor an agent for social change as his contemporary-cum-rival Jean-Luc Godard staunchly maintains. For him, it is a woman. And like Alphonse (played by Jean-Pierre Leaud) in Day for Night discovers, woman is magic, and also, she isn’t. Film, like woman, is an enigma, a temptress, a lover.

This unrequited attainment of woman as a concept marks Truffaut’s entire body of work. From his early short, Les Mistons, about the pre-pubescent puppy love a group of kids share for an older woman, to the entire Antoine Doinel series, which placed Truffaut’s representative (Leaud) in and out of the arms of women he could not keep, Truffaut’s filmic pursuit of women haunts his best work and is absent from his worst. For more proof, see Mississippi Mermaid, The Soft Skin, The Woman Next Door,The Man Who Loved Women, and Jules and Jim. Even the titles of these films evoke the wistful courtship of the feminine mystique.

In Day for Night, he blends his two loves. Ever the romantic, Truffaut brings us into his passionate affair with cinema. Curiously though, it is not the flickering fantasy of the darkened room that he invites us to—that communal experience we all share when the lights dim and pictures flash before our eyes—but rather, the gritty nuts and bolts of the movie machine. He loves not the product of cinema alone, but the process through which it is made—the war to create. And yet, he shirks a cinéma vérité documentary style with handheld cameras and natural light. The reality of the illusion is instead glamorized and polished, as Truffaut employs an array of filmic effects: jump cuts, freeze frames, black and white, and voice-over. At certain times, the camera is hand-held, at others it’s on a tripod or gliding on a dolly track, crane, or even helicopter. Truffaut’s lust for filmmaking drips onto the film, treating the camera, rolling film strips, props, etc. as if they were legs and breasts—body parts to be admired with dreamlike quality. In fact, the light throughout is soft and filled in every space; the color, warm and familial. Georges Delerue’s score wonderfully mirrors the blend of the technical and the artistic with a rigid pomp and circumstance sung by choral strings and French horns. Montages occur throughout the film, flowing through the set, illuminating everything and everyone involved. At the end of one such ‘love scene,' the camera, seen from above, ascends into the sky on a crane. Upon reaching its apex, the camera tilts and pans around, shooting directly into our camera, our eyes, at us. How much more can Truffaut pull us into this love affair?

Beneath the bleeding romance of Day for Night, however, resides a deeper, more profound theme: the dichotomy of illusion and reality. Here, the dividing line is drawn at the first scene. The film opens with a scene from Meet Pamela (the illusion) when it is abruptly stopped by Truffaut himself, emphatically yelling “cut” and thrusting us into Day for Night (reality, at least, the reality of Day for Night). With the curtain now drawn, Truffaut invites us into the filmmaker’s world. We become part of the crew. The camera, almost always at eye level with its subject is empathetic to the characters. We are in this romance with them. This wonderful tour, led by Truffaut himself as the director Ferrand, guides us through the beautiful illusion with its equally beautiful and even more exciting reality. As the drama of Meet Pamela (illusion) is meticulously fabricated, an unpredictable soap opera (reality) unfolds behind the camera. Truffaut shows us both sides, acting himself as the mirror between reality and reflection.

This theme of illusion and reality permeates the film. When it is discovered an actress is pregnant (reality), the producer attempts to fit it into the film (illusion) before Ferrand (Truffaut) rejects it as a disruption to the rest of the illusion. When Severine (Cortese) stumbles through an emotional scene, opening the wrong door again and again, one of the crew reveals to another that her son has leukemia. Her reality belies the drama of the illusion and she is unable to bear the charade. When the veteran actor Alexandre (Jean-Pierre Aumont), with a reputation for being a ladies’ man (illusion), arrives at the airport to pick up his friend, he greets a young man who in fact turns out to be his lover (reality). Truffaut continues to break down the walls of illusion between the film and the film within. A late night conversation with an actress becomes the next day’s rewritten lines. The plot of Day for Night slowly begins to mirror the plot of Meet Pamela. The actors, who are playing actors, recite lines of reciting lines. At one point, Leaud’s character sits in a theater watching his dailies, mouthing the lines along with his onscreen self. One can imagine Leaud sitting in a theater in France, watching himself on a screen watch himself on a screen, each one mouthing the actor's lines. In fact, with the exception of Alexandre, all of the actors at some point gaze into their reflection in the mirror. On one level, Truffaut is pushing the actors to play themselves as he seeks to blend the illusion (Meet Pamela) with the other illusion (Day for Night) and ultimately, with reality. Throughout all this, Truffaut is the painstaking orchestrator, consumed in his creation. A firm believer in the idea and role of the auteur, he places his most personal, most convicted, and most passionate stamp on Day for Night.

In Truffaut’s loving reverence of film, it is king. But, it is not reality. Film is not life at 24 frames per second. The real drama of life exists not on screen, but is only augmented by it. Like all significant art, film is the mirror through which we can see and understand our own humanity. Inferior to reality? Yes. Unnecessary to it? No. After all, it’s in our nature, as Truffaut’s Ferrand observes: "People used to stare at fires, now they watch TV. We need to see moving images, especially after dinner."

Posted by:

Robbie Ikegami

Dec 12, 2011 9:41pm