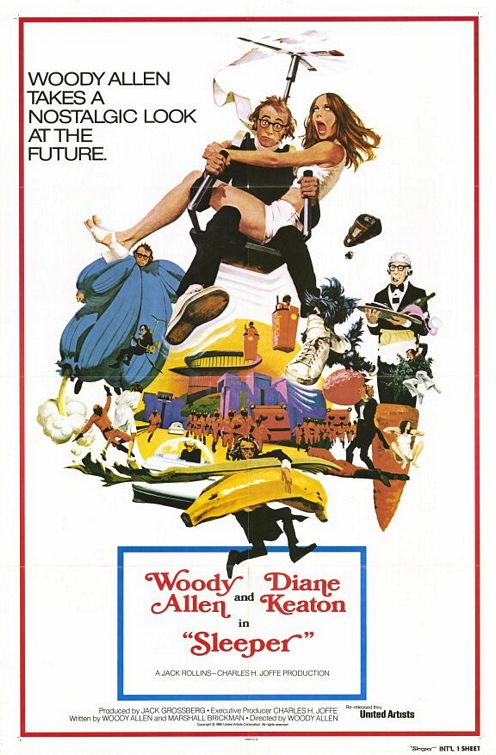

Sleeper

Most films about the future seem optimistic about human intelligence levels rising, with Mike Judge’s depressing comedy Idiocracy being an exception. Woody Allen’s Sleeper splits the difference: the technology and science have evolved but people have gotten shallower. Since ’73 his vision looks to be almost prophetic. As a follow up to Every Thing You Always Wanted to Know about Sex * But Were Afraid to Ask, Sleeper was his most polished film at that point. It was the peak of Woody’s slapstick phase, just four years before his evolutionary jump into the more mature filmmaker he would become with Annie Hall and Manhattan (both films co-written with Marshall Brickman, who also worked on the Sleeper script). Kinda, sorta, slightly based on H.G. Wells’s 1899 novel When the Sleeper Wakes, it’s a film that, because of the science-fiction element and the high laugh count, has always been considered one of his more admired and easily digestible films from his non-fans.

Most films about the future seem optimistic about human intelligence levels rising, with Mike Judge’s depressing comedy Idiocracy being an exception. Woody Allen’s Sleeper splits the difference: the technology and science have evolved but people have gotten shallower. Since ’73 his vision looks to be almost prophetic. As a follow up to Every Thing You Always Wanted to Know about Sex * But Were Afraid to Ask, Sleeper was his most polished film at that point. It was the peak of Woody’s slapstick phase, just four years before his evolutionary jump into the more mature filmmaker he would become with Annie Hall and Manhattan (both films co-written with Marshall Brickman, who also worked on the Sleeper script). Kinda, sorta, slightly based on H.G. Wells’s 1899 novel When the Sleeper Wakes, it’s a film that, because of the science-fiction element and the high laugh count, has always been considered one of his more admired and easily digestible films from his non-fans.

In 1973, Miles Monroe (Allen), owner of the Happy Carrot Health-Food store, is put into a scientific sleep chamber, without his knowledge, and finally revived two-hundred years later in 2173. He wakes up in a futuristic American police state (similar to so many movie future societies from Logan’s Run to Conquest of the Planet of the Apes to The Hunger Games). The rebels need him because he’s the only citizen without an identification number. He ends up helping them by posing as a robot servant for a dingy socialite, Luna Schlosser (Diane Keaton, working with Woody for the second time after Play It Again, Sam. This was the first of seven films she would appear in that he would direct). She lives in a totally pretentious bubble with no clue to the world around her. But after finally revealing his true identity to her, he kidnaps her and they go on the run, fall in love, and she becomes a born-again rebel.

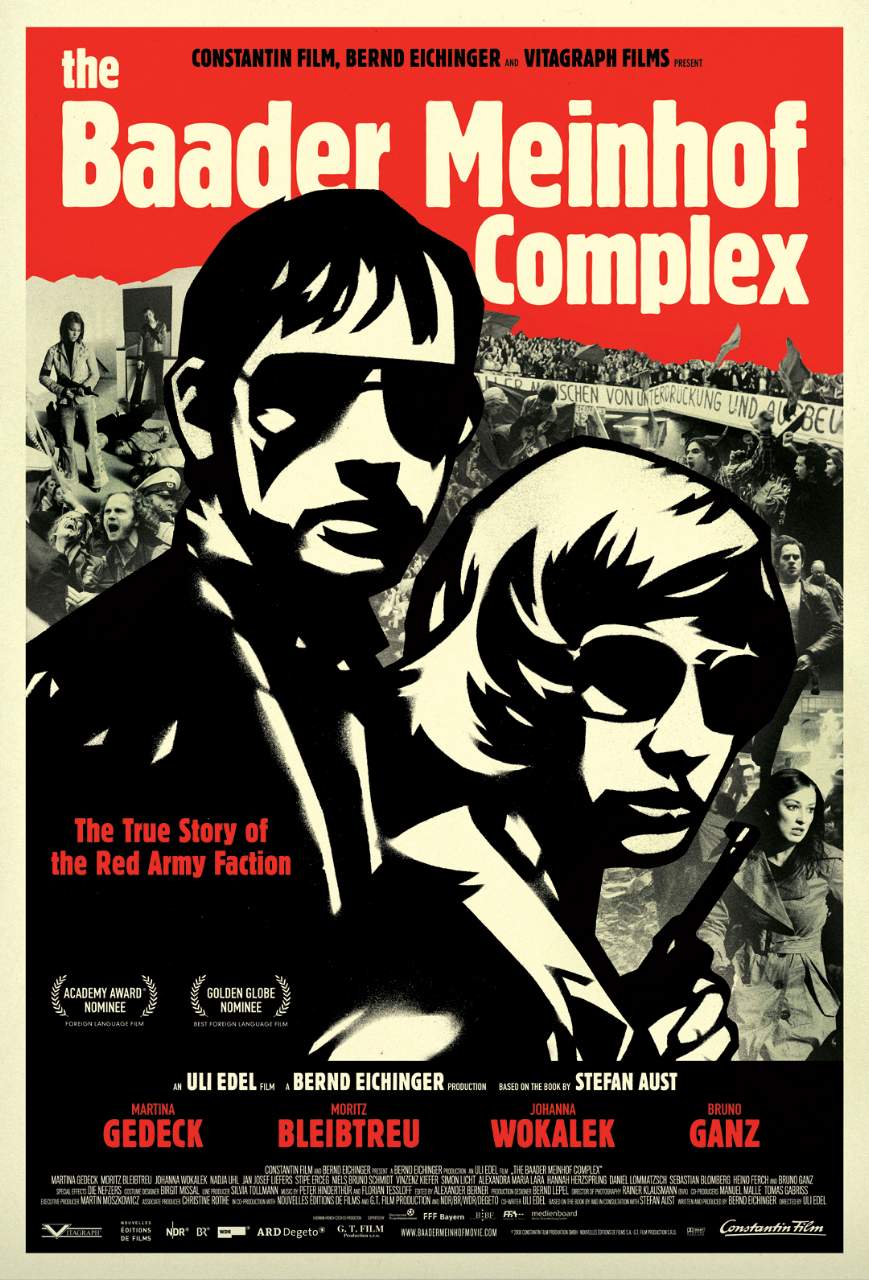

The Baader Meinhof Complex

Stunningly shot and perfectly conceived, the best historical political thriller in recent years is director Uli Edel’s The Baader Meinhof Complex, a film about the West German radical group, the RAF—Red Army Faction—who reigned from 1967–77. Inspired by cultural revolutions in Paris and Czechoslovakia they took the baton from American outfits like the Black Panthers and the Weathermen and raised the stakes by about a hundred. Unlike other great political films like Z, State of Siege, Bloody Sunday, Che, and even Munich, Edel, best known for his American film Last Exit to Brooklyn back in ’89, does not go with the traditional handheld docu-realism style but a slick look, with long dolly shots (ala Boogie Nights) and a smooth editing style. In this age of terrorism paranoia, here is a film like Battle of Algiers that tries to explain the motives behind the action, but not justify them or even glamorize them. These were true believers in the cause but also groovy party rebels who just didn’t want to be like their parents and broke from the longstanding rule of German conformity.

Stunningly shot and perfectly conceived, the best historical political thriller in recent years is director Uli Edel’s The Baader Meinhof Complex, a film about the West German radical group, the RAF—Red Army Faction—who reigned from 1967–77. Inspired by cultural revolutions in Paris and Czechoslovakia they took the baton from American outfits like the Black Panthers and the Weathermen and raised the stakes by about a hundred. Unlike other great political films like Z, State of Siege, Bloody Sunday, Che, and even Munich, Edel, best known for his American film Last Exit to Brooklyn back in ’89, does not go with the traditional handheld docu-realism style but a slick look, with long dolly shots (ala Boogie Nights) and a smooth editing style. In this age of terrorism paranoia, here is a film like Battle of Algiers that tries to explain the motives behind the action, but not justify them or even glamorize them. These were true believers in the cause but also groovy party rebels who just didn’t want to be like their parents and broke from the longstanding rule of German conformity.

German counter-culture radicals of the ’60s and ’70s have been portrayed in both real life and fictional accounts in films a number of times before; most famously there was Volker Schlondorff's The Legend of Rita and Rainer Werner Fassbinder's The Third Generation. Schlondorff also directed with his then wife, Margarethe von Trotta, the classic The Lost Honor of Katharina Blum, while Marco Bellocchio’s Good Morning, Night covered the Italian counterparts in the same period. And more recently the story of Uschi Obermaier, the ’70s German terrorist/supermodel, had her wild life made into a movie, Eight Miles High. And then there was Olivier Assayas’s epic Carlos about the international super criminal. So this is fertile ground that has been covered from many angles for the last 30-something years, but The Baader Meinhof Complex feels like the most authoritative, final statement on the subject, at least from the German side of history.

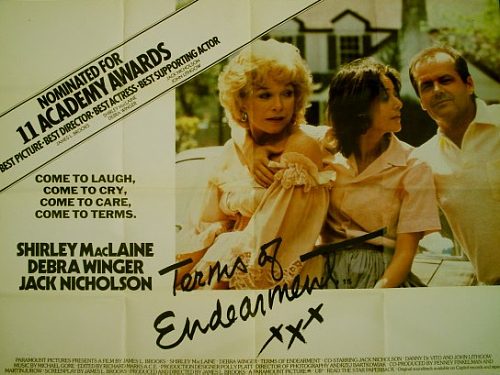

Terms of Endearment

Sometimes films about women are unfairly called “chick flicks,” or more recently, if it involves illness, it can be written off as a Lifetime flick or disease-of-the-week TV movie. Terms of Endearment is neither, though it’s sometimes too elegantly clean in its look; in its heart it’s a big, complicated story with multi- dimensional characters that works perfectly as both a smart comedy and a moving drama. Following mother and daughter, Aurora (Shirley MacLaine) and Emma (Debra Winger) over decades, their tricky relationship to each other and others, like a ‘70s-style flick, sometimes it’s hard to like these women or fully understand their motives, just like real people, not movie creations. Besides MacLaine and Winger giving the performances of their careers, the film is loaded with pedigree behind it. Making his directing debut is the legendary TV writer and creator, James L. Brooks (The Mary Tyler Moore Show, Lou Grant,Taxi) and it has his now familiar fingerprints on every frame. Brooks also wrote the script, based on a book by the great novelist Larry McMurtry (Hud, The Last Picture Show, Lonesome Dove). It was shot by the respected Polish cinematographer Andrzej Bartkowiak (Prince of the City, The Verdict), the crisp look now the standard for these kinds of movies. The great Polly Platt (Paper Moon) designed it, Richard Marks (The Godfather Part II) was the editor, and Michael Gore (Fame) provides the dainty score. Oh, and in a big supporting performance Jack Nicholson wanders in and devours the screen, brilliantly.

Sometimes films about women are unfairly called “chick flicks,” or more recently, if it involves illness, it can be written off as a Lifetime flick or disease-of-the-week TV movie. Terms of Endearment is neither, though it’s sometimes too elegantly clean in its look; in its heart it’s a big, complicated story with multi- dimensional characters that works perfectly as both a smart comedy and a moving drama. Following mother and daughter, Aurora (Shirley MacLaine) and Emma (Debra Winger) over decades, their tricky relationship to each other and others, like a ‘70s-style flick, sometimes it’s hard to like these women or fully understand their motives, just like real people, not movie creations. Besides MacLaine and Winger giving the performances of their careers, the film is loaded with pedigree behind it. Making his directing debut is the legendary TV writer and creator, James L. Brooks (The Mary Tyler Moore Show, Lou Grant,Taxi) and it has his now familiar fingerprints on every frame. Brooks also wrote the script, based on a book by the great novelist Larry McMurtry (Hud, The Last Picture Show, Lonesome Dove). It was shot by the respected Polish cinematographer Andrzej Bartkowiak (Prince of the City, The Verdict), the crisp look now the standard for these kinds of movies. The great Polly Platt (Paper Moon) designed it, Richard Marks (The Godfather Part II) was the editor, and Michael Gore (Fame) provides the dainty score. Oh, and in a big supporting performance Jack Nicholson wanders in and devours the screen, brilliantly.

The wealthy widow Aurora is a deeply caring but overly needy mother to her only daughter, Emma. She doesn’t approve of Emma’s choice of husband, the skirt-chasing college professor Flap Horton (Jeff Daniels) who drags Emma from one sleepy Midwest college town after another and, over the course of several years, they have three kids together. While a half-assed father, he usually also has an attractive young coed on the side. Everything Emma does doesn’t seem to meet Aurora’s high expectations; out of desperation and loneliness in her lousy marriage she even has a brief affair with a nerdy married banker (John Lithgow, who had become a major character actor after a bravura performance in The World According to Garp).

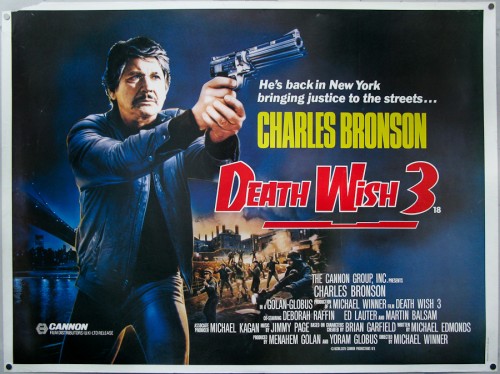

Death Wish 3

The first three Death Wish films can easily be categorized as the good, the bad, and the ugly. The first one was a good, quality piece of exploitation pulp. The second is bad because it was dull and boring. The third is the ugly and isn’t ugly usually more interesting? In this case, it is. Death Wish 3 could be called bad because it’s so ridiculous and over the top but that’s also what makes it so good—it’s ridiculous and over the top. And any resemblance to the realism of the first film has been totally thrown out the window and now plays like a cartoon spoof of the vigilante genre. And forget the later Death Wish flicks to come; still starring Grandpa Charles Bronson, Death Wish 4: the Crackdown and Death Wish 5: the Face of Death, they are utterly forgettable and worse, unwatchable. But the middle child, Death Wish 3, is something special in a lovably ugly dog way.

The first three Death Wish films can easily be categorized as the good, the bad, and the ugly. The first one was a good, quality piece of exploitation pulp. The second is bad because it was dull and boring. The third is the ugly and isn’t ugly usually more interesting? In this case, it is. Death Wish 3 could be called bad because it’s so ridiculous and over the top but that’s also what makes it so good—it’s ridiculous and over the top. And any resemblance to the realism of the first film has been totally thrown out the window and now plays like a cartoon spoof of the vigilante genre. And forget the later Death Wish flicks to come; still starring Grandpa Charles Bronson, Death Wish 4: the Crackdown and Death Wish 5: the Face of Death, they are utterly forgettable and worse, unwatchable. But the middle child, Death Wish 3, is something special in a lovably ugly dog way.

In the first flick, Death Wish back in ’74, Paul Kersey (Charles Bronson) was a respectable NY architect, but when his wife was murdered by some savage street brutes he became a stone cold vigilante, knocking them off. While less credibly in Death Wish II, Bronson was in LA and got all killy again to avenge the memory of his maid. By the time 3 begins he seems to be a guy who just casually kills goons at will. Hoping to take a relaxing vacation in the projects of Brooklyn by visiting his old war buddy, he arrives to find his friend dying, having just been beaten to a pulp by the local street creeps. The cops arrest him for the murder; after giving him a working over, Chief Shriker (the great B-movie actor, Ed Lauter of The Longest Yard) cuts a deal with him, letting him go if he will go knock off some of the ‘hood rats (a multi-racial gang of central casting punkers, biker types, and “Beat It” dancers).

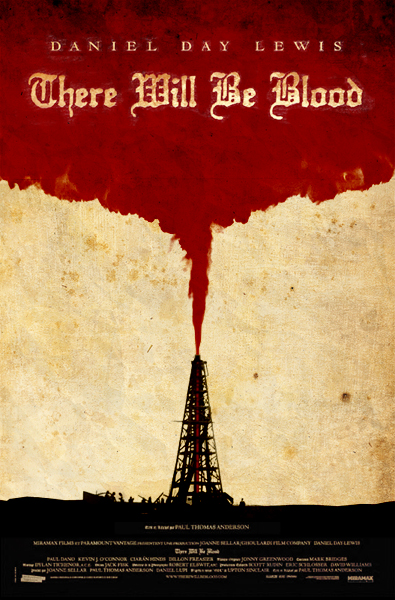

There Will Be Blood

For director/writer Paul Thomas Anderson, his first film Hard Eight was a solid gambling thriller while Punch-Drunk Love gave him quirky Lynchian street cred, but it was his double dose of sprawling LA ensemble pieces Magnolia and Boogie Nights that put him in the big, big-time. Though those are two dazzlingly shot and acted flicks, there is a sense of Altman-esqe gimmickry and MapQuest symmetry about them. It really was his fifth feature, There Will Be Blood, which made Anderson more then just a hip taste of the day. Apparently the film was partially inspired by Upton Sinclair’s 1927 novel, Oil!, with the setting moved from the 1920s to the turn of the century. The film works best when sticking to the source material, detailing the beginnings of the oil boom; it tends to loose itself when veering off-course into Anderson’s morality battle. Regardless, it’s always watchable thanks first and foremost to the epic performance from the great Irish actor Daniel Day-Lewis, who channels the voice, look, and attitude of director/actor John Huston (even more accurately then Clint Eastwood did in White Hunter Black Heart). There Will Be Blood proves that when Anderson has the right, focused material he has as much clear-eyed vision as anyone making movies these days.

For director/writer Paul Thomas Anderson, his first film Hard Eight was a solid gambling thriller while Punch-Drunk Love gave him quirky Lynchian street cred, but it was his double dose of sprawling LA ensemble pieces Magnolia and Boogie Nights that put him in the big, big-time. Though those are two dazzlingly shot and acted flicks, there is a sense of Altman-esqe gimmickry and MapQuest symmetry about them. It really was his fifth feature, There Will Be Blood, which made Anderson more then just a hip taste of the day. Apparently the film was partially inspired by Upton Sinclair’s 1927 novel, Oil!, with the setting moved from the 1920s to the turn of the century. The film works best when sticking to the source material, detailing the beginnings of the oil boom; it tends to loose itself when veering off-course into Anderson’s morality battle. Regardless, it’s always watchable thanks first and foremost to the epic performance from the great Irish actor Daniel Day-Lewis, who channels the voice, look, and attitude of director/actor John Huston (even more accurately then Clint Eastwood did in White Hunter Black Heart). There Will Be Blood proves that when Anderson has the right, focused material he has as much clear-eyed vision as anyone making movies these days.

Spanning decades in the life and career of Daniel Plainview (Day-Lewis), a prospector who gets into the oil game, the films opens with a stunning dialogue-free 15 minutes as Plainview digs for oil and adopts a baby boy from a worker who was killed. He has a knack for finding oil and becomes more and more successful. Though he is a greedy manipulator he seems to be a devoted dad, referring to his son as his business partner. However, after the kid goes deaf in an on-site accident he seems to lose his patience for fathering. Getting a tip from a young man named Paul Sunday (Paul Dano) about a piece of land that may have oil, he swindles the family out of their land and gets very rich with the oil he takes from their ground. Unfortunately, Paul’s twin brother Eli (also Dano, which at first seems confusing) is a true believer preacher who becomes a lifelong headache for the faithless entrepreneur. He also is joined briefly by a guy claiming to be his long-lost half brother (Kevin J. O’Connor) and has minor spats with the major oil companies.

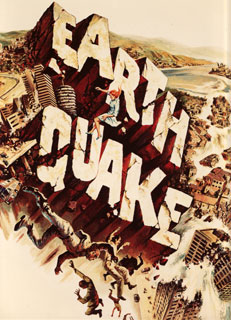

Earthquake

Jump started by the success of the movie Airport in 1970, the “disaster movie” was a 1970’s cultural phenomenon, taking the soap-opera mold of Grand Hotel and putting a bunch of actors, ranging from big stars to has-beens all eager to cash their checks, into a dangerous situation with now cornball special effects. The best was The Poseidon Adventure and the biggest was The Towering Inferno (which inexplicably got a Best Picture Oscar nomination). But the most ambitiously awkward may’ve been Earthquake. The film was originally released extra loud in something called "Sensurround” and featured cameramen shaking cameras while Styrofoam bricks fell on extras. It was directed by Mark Robson (Valley of the Dolls) and written by Mario Puzo (yes, that’s right, Mario–the Godfather–Puzo, and he’s not the only major talent slumming here), though someone named George Fox also got a screenwriting credit as well, the only film for which he’s credited. Earthquake may not have been very good but as a cultural curiosity it’s fascinating, as a travelogue of mid-’70s Los Angeles it’s invaluable, and as a piece of ridiculous pop-junk it’s totally entertaining.

Jump started by the success of the movie Airport in 1970, the “disaster movie” was a 1970’s cultural phenomenon, taking the soap-opera mold of Grand Hotel and putting a bunch of actors, ranging from big stars to has-beens all eager to cash their checks, into a dangerous situation with now cornball special effects. The best was The Poseidon Adventure and the biggest was The Towering Inferno (which inexplicably got a Best Picture Oscar nomination). But the most ambitiously awkward may’ve been Earthquake. The film was originally released extra loud in something called "Sensurround” and featured cameramen shaking cameras while Styrofoam bricks fell on extras. It was directed by Mark Robson (Valley of the Dolls) and written by Mario Puzo (yes, that’s right, Mario–the Godfather–Puzo, and he’s not the only major talent slumming here), though someone named George Fox also got a screenwriting credit as well, the only film for which he’s credited. Earthquake may not have been very good but as a cultural curiosity it’s fascinating, as a travelogue of mid-’70s Los Angeles it’s invaluable, and as a piece of ridiculous pop-junk it’s totally entertaining.

The goofball introduction to the characters goes something like this... hunky architect Stewart Graff (Charlton Heston) is in a dead marriage to Remy (Ava Gardner) and having a boring affair with a young struggling actress, Denise (Genevieve Bujold, a sorta less sexy ’70s version of Audrey Tautou), who is a single mom with an annoying son, Cory (the terrible actor but coolly named Tiger Williams). Meanwhile, maverick cop Lew Slade (George Kennedy) gets in trouble for punching out another cop after a car chase ends up ruining Zsa Zsa Gabor’s hedges, so he heads to the local dive to get drunk (which features a hilarious Walter Matthau, billed as Walter Matuschanskayasky, playing an inebriated, pimped-out bar fly). Would-be Evel Knievel motorcycle stunt driver Miles Quade (Richard Roundtree) and his manager, Sal (Gabriel Dell) are planning a big new loop-to-loop stunt to impress some Vegas hotel guys. Sal’s hot younger sister Rosa (Victoria Principle) is there to bring sex appeal to the act but she’s stalked by a creepy grocery clerk/national guardsman (the creepy Marjoe Gortner, most famous for appearing as himself in the documentary Marjoe, before becoming a TV and B-movie staple of the late ’70s and early ’80s). Also popping up are Lloyd Nolan as a doctor, Lorne Greene as Gardner’s father (though in real life he’s barely seven years older than her), and a bunch of earthquake studying scientists and maintenance men watching over the Mulholland Dam (actually the real life Hollywood Reservoir), as if there was a giant waterway above Los Angeles that needed to be dammed up.

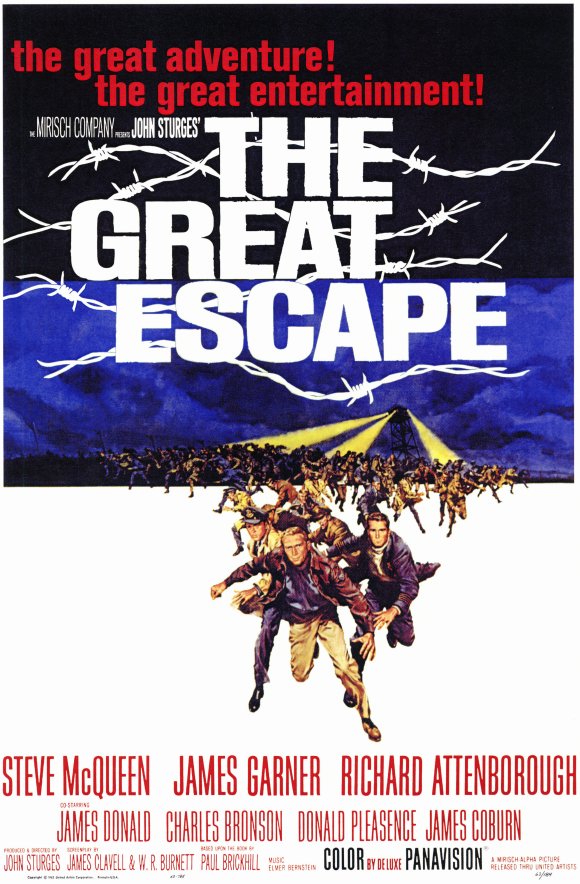

The Great Escape

After putting together a super team for the exciting western The Magnificent Seven, director John Sturges assembled the rat-pack for the much duller western, Sergeants 3; so down but not out, Sturges reconvened some of his Magnificent Seven cast for his masterpiece, the WWII POW epic The Great Escape. With apologies to King Rat, Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence, Empire of the Sun, The Hill, and even Victory, the official, no- arguments-allowed Big Three of POW flicks are (in order of release): Stalag 17 then The Bridge on the River Kwai, and finally The Great Escape; you can argue which of the Big Three is tops, but all three are wonderful and will rank in any war movie best-of list.

After putting together a super team for the exciting western The Magnificent Seven, director John Sturges assembled the rat-pack for the much duller western, Sergeants 3; so down but not out, Sturges reconvened some of his Magnificent Seven cast for his masterpiece, the WWII POW epic The Great Escape. With apologies to King Rat, Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence, Empire of the Sun, The Hill, and even Victory, the official, no- arguments-allowed Big Three of POW flicks are (in order of release): Stalag 17 then The Bridge on the River Kwai, and finally The Great Escape; you can argue which of the Big Three is tops, but all three are wonderful and will rank in any war movie best-of list.

Like the recent action flicks The Expendables or The Avengers, The Great Escape is about assembling the team of super cool (now familiar) faces. The Magnificent Seven put the young supporting Steve McQueen on the A-List. Here, he’s the top dog and it may be his most memorable role; joined by two of the other Seven co-stars, Charles Bronson and James Coburn (who would both go on to be big stars in the years to come), with James Garner bringing his awe-shucks charm that would captivate TV audiences for decades and, rounding out the team, the British actors Richard Attenborough, Donald Pleasence, David McCallum, and James Donald (who was also in The Bridge on the River Kwai), lending some class to the team.

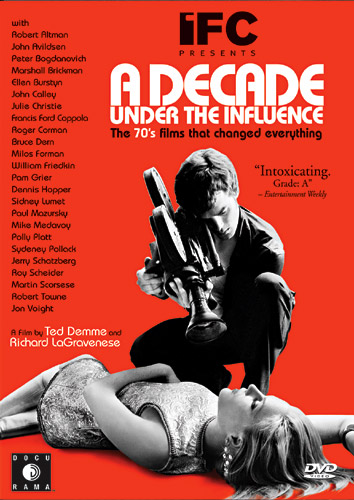

A Decade Under the Influence

Playing on the title of the groundbreaking John Cassavetes film A Woman Under the Influence, or maybe ’70s cokehead producer Julia Phillips’s memoir Driving Under the Affluence, the IFC-produced, three-part documentary A Decade Under the Influence is a fawning but wildly entertaining tribute to the films of the ’70s (actually 1967 onwards) and the maverick filmmakers who reinvented Hollywood. It’s the perfect film companion to Peter Biskind's incredibly readable book Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, which also spawned a BBC-produced documentary with the same name. The IFC series may come out slightly on top if only because it’s an hour longer and, at just 119 minutes, the BBC flick may not cover enough ground, while A Decade Under the Influence is crammed wall to wall with clips and interviews. For anyone who romanticizes this era in film (like me) this is three hours of pure, giddy love.

Playing on the title of the groundbreaking John Cassavetes film A Woman Under the Influence, or maybe ’70s cokehead producer Julia Phillips’s memoir Driving Under the Affluence, the IFC-produced, three-part documentary A Decade Under the Influence is a fawning but wildly entertaining tribute to the films of the ’70s (actually 1967 onwards) and the maverick filmmakers who reinvented Hollywood. It’s the perfect film companion to Peter Biskind's incredibly readable book Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, which also spawned a BBC-produced documentary with the same name. The IFC series may come out slightly on top if only because it’s an hour longer and, at just 119 minutes, the BBC flick may not cover enough ground, while A Decade Under the Influence is crammed wall to wall with clips and interviews. For anyone who romanticizes this era in film (like me) this is three hours of pure, giddy love.

Episode One: Influences and Independents, begins with the big gaudy premiere of the crappy big gaudy musical Hello Dolly in ’69; the thesis: that bomb marked the end of the studio era. An intelligent group of interviewees, including Francis Ford Coppola, Dennis Hopper, and William Friedkin, give us the set up: the civil rights movement, Vietnam War, the women's movement, ’60s innovative rock & roll and later Watergate, the formation of the counter culture, and youth movement had a generation of people asking why and breaking the rules. For filmmakers who were seeing the art house foreign films of Godard, Kurosawa, Truffaut, Antonioni, Bergman, and Fellini (and of course Julie Christie throws in the working class films of early ’60s England) the current beach flicks, musicals, and romantic comedies of Hollywood no longer seemed relevant. When Arthur Penn took influence from the French New Wave (who were influenced by American film noir and gangster flicks) and came up with his sexually frank and violent Bonnie and Clyde, it opened the floodgates for a new kind of American film. With Roger Corman and BBS (Bob Rafelson, Bert Schneider, and Steve Blauner) creating a new class of filmmakers who could work cheap while learning their trade and John Cassavetes making his homemade indie movies, the idea for the “’70s flick” was solidified. Those early influential flicks of the era are recalled and analyzed, including Easy Rider, Targets, Midnight Cowboy, The French Connection, and The Last Picture Show. But it’s not all classics; less memorable movies like Joe and Hi, Mom! are also included and even Dirty Harry is given props as an obvious influence.

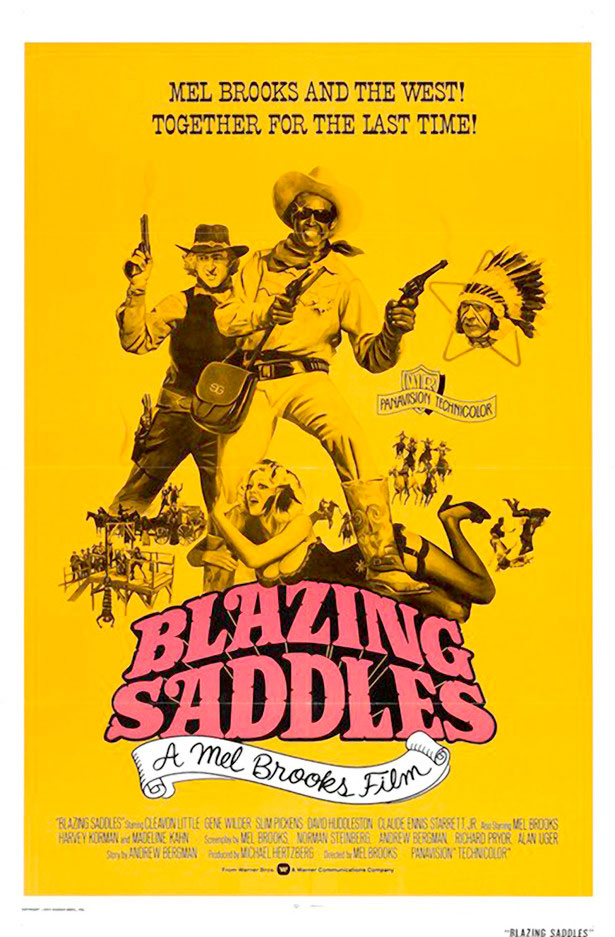

Blazing Saddles

Once upon a time in the golden period of films known as the 1970s, Mel Brooks was, along with Woody Allen, the biggest directing name in comedy. Both had been on the legendary writing staff of Sid Caesar's Your Show of Shows in the '50s (along with Neil Simon and Carl Reiner) and both brought a distinctly Jewish tone to their slapstick. While Allen represented the Manhattan highbrow, Brooks’s style lurked more in the offensively low end Borscht Belt style. By the '80s, when Allen's status raised to the level of genius, Brooks’s comedy had already become passe and completely juvenile, working in the obvious (Spaceballs, Dracula: Dead and Loving It, etc.). But his early string of comedies, from The Producers through High Anxiety, created a lot of laughs, peaking in 1974 with two comic masterpieces: Young Frankenstein and, maybe even better, the bawdy western spoof Blazing Saddles.

Once upon a time in the golden period of films known as the 1970s, Mel Brooks was, along with Woody Allen, the biggest directing name in comedy. Both had been on the legendary writing staff of Sid Caesar's Your Show of Shows in the '50s (along with Neil Simon and Carl Reiner) and both brought a distinctly Jewish tone to their slapstick. While Allen represented the Manhattan highbrow, Brooks’s style lurked more in the offensively low end Borscht Belt style. By the '80s, when Allen's status raised to the level of genius, Brooks’s comedy had already become passe and completely juvenile, working in the obvious (Spaceballs, Dracula: Dead and Loving It, etc.). But his early string of comedies, from The Producers through High Anxiety, created a lot of laughs, peaking in 1974 with two comic masterpieces: Young Frankenstein and, maybe even better, the bawdy western spoof Blazing Saddles.

The western spoof is almost as old as the western itself—you had Laurel & Hardy in Way Out West, The Marx Brothers in Go West, Mae West and W.C. Fields did My Little Chickadee, and Bob Hope had The Paleface and then Son of Paleface, not to mention Destry Rides Again with Marlene Dietrich (which Blazing Saddles actually directly spoofs). The '60s saw an examining of the western most directly through the Italian spaghetti westerns and American western comedies such as Cat Ballou and Support Your Local Sheriff! In the '70s, the reexamining went to the extreme as the western was turned in on itself and poked at by post-modernists with films as broad as Jodorowsky’s El Topo, Altman’s Buffalo Bill and the Indians, or Sitting Bull's History Lesson, to the sci-fi camp of Westworld. Blazing Saddles is more than a spoof; it’s one of the rare big laugh comedies that actually has something to say about contemporary racial politics, making it much closer to the later, intellectually ambitious films than the earlier yuk-fests.

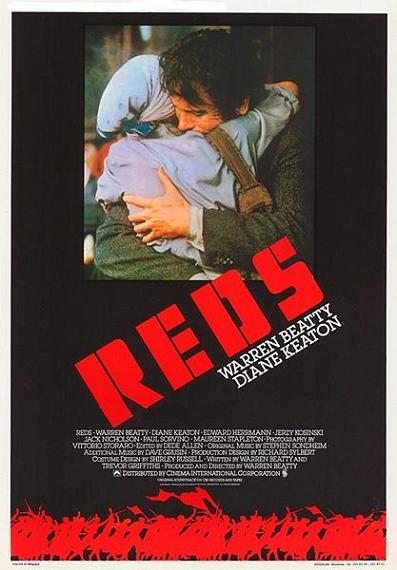

Reds

In 1981, with newly elected rah-rah American president Ronald Reagan taking office, an anti-Communist, anti-Soviet ardor was in full swing. So it was extra amazingly audacious that pretty-boy actor Warren Beatty was able to get his giant bio of Communist journalist John Reed made. Reed, the only American buried in Russia’s Kremlin, isn’t exactly a household name and Reds the movie, clocking in at an epic 194 minutes, wasn’t exactly a sure thing at the box-office (matter of fact, despite winning a bunch of awards, it was considered a financial disappointment in its day). Reds really is a tribute to the passion of Warren Beatty’s grand vision; he produced, directed, and co-wrote the screenplay with British playwright Trevor Griffiths (with uncredited contributions from Elaine May) and managed to put together an impressive cast to back him up (Diane Keaton, Jack Nicholson, Edward Herrmann, Paul Sorvino, Maureen Stapleton, Gene Hackman, etc). Ironic: a rich movie star makes a big expensive movie (with corporate funds) about an anti-wealth guy. In the Doctor Zhivago tradition, Reds is one of those sweeping literate love stories which was shot for over a year in five different countries; but underneath that sweep it’s a very personal and intimate little movie.

In 1981, with newly elected rah-rah American president Ronald Reagan taking office, an anti-Communist, anti-Soviet ardor was in full swing. So it was extra amazingly audacious that pretty-boy actor Warren Beatty was able to get his giant bio of Communist journalist John Reed made. Reed, the only American buried in Russia’s Kremlin, isn’t exactly a household name and Reds the movie, clocking in at an epic 194 minutes, wasn’t exactly a sure thing at the box-office (matter of fact, despite winning a bunch of awards, it was considered a financial disappointment in its day). Reds really is a tribute to the passion of Warren Beatty’s grand vision; he produced, directed, and co-wrote the screenplay with British playwright Trevor Griffiths (with uncredited contributions from Elaine May) and managed to put together an impressive cast to back him up (Diane Keaton, Jack Nicholson, Edward Herrmann, Paul Sorvino, Maureen Stapleton, Gene Hackman, etc). Ironic: a rich movie star makes a big expensive movie (with corporate funds) about an anti-wealth guy. In the Doctor Zhivago tradition, Reds is one of those sweeping literate love stories which was shot for over a year in five different countries; but underneath that sweep it’s a very personal and intimate little movie.

After covering events in Russia, journalist John Reed (Beatty) returns to his home town of Portland to raise money for his ultra-left newspaper. There, he meets and has a fling with a married socialite named Louise Bryant (Keaton) and invites her back to New York's bohemian Greenwich Village where they both hang with many of the famous radicals of their day, like the outspoken anarchist Emma Goldman (Stapleton). Reed encourages Bryant to become a writer herself; she develops her own form of ahead-of- her-time feminism while he throws himself deeper into the Communist Party. After the couple moves to Provincetown, Massachusetts, Reed travels the country to cover the presidential election, while Bryant begins an affair with Reed’s friend, the tortured playwright Eugene O’Neill (Nicholson), the one intellectual who seems to respect her. Then, Reed and Bryant patch things up and first travel to write about the war in Europe (that would be WWI) and then to cover the revolution in Russia of 1917. And that’s just the first half.