Movies We Like

Handpicked By The Amoeba Staff

Films selected and reviewed by discerning movie buffs, television junkies, and documentary diehards (a.k.a. our staff).

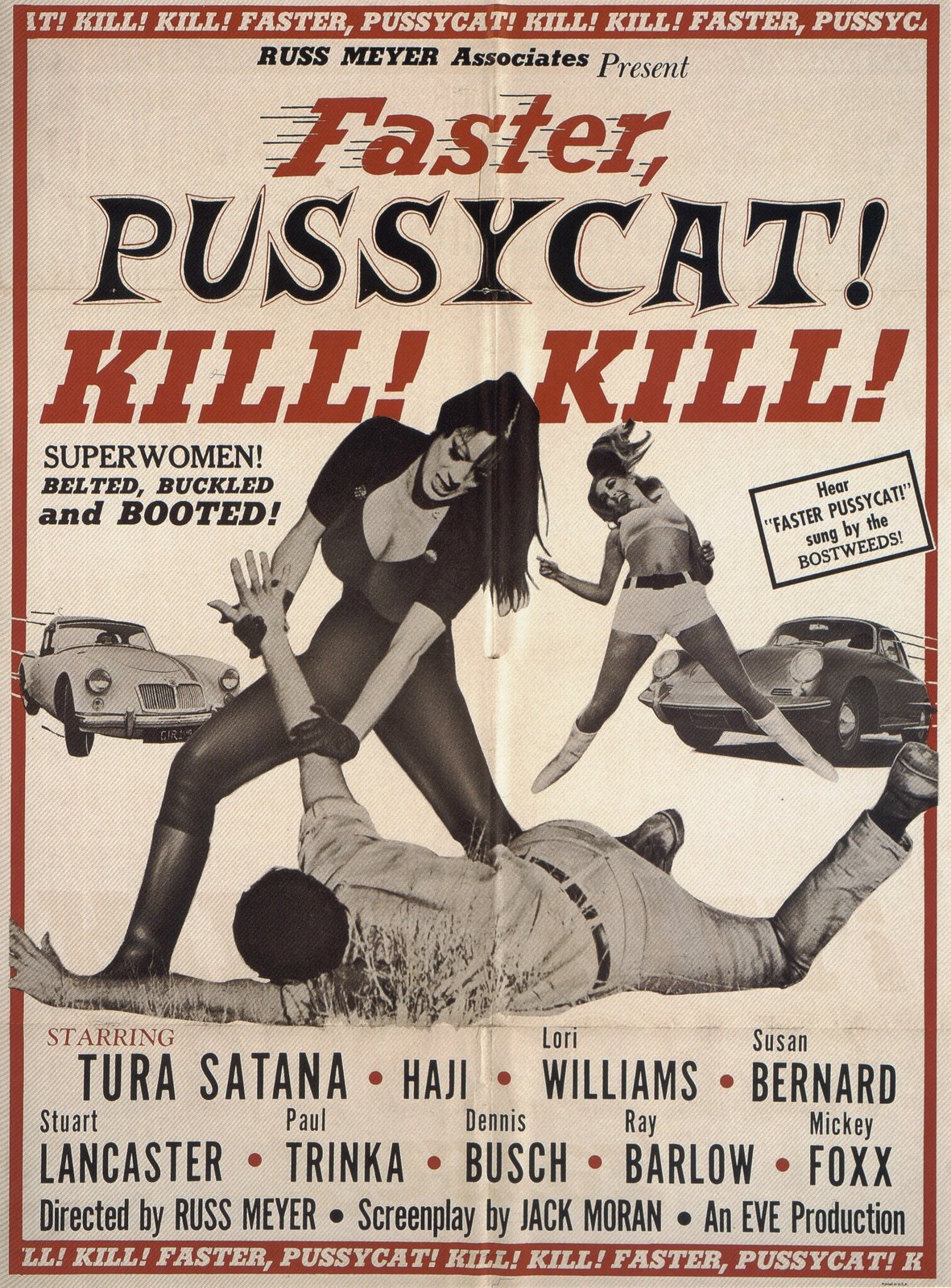

Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill!

Russ Meyer has brought a plethora of tales that feature femme fatales, vixens, and unapologetic ladies, but none are as flawless as Faster, Pussycat! Aside from being ahead of its time by approaching women as forces to be reckoned with—not trampled on—Meyer employed various techniques that were rarely used in low budget film. The frame composition in the action sequences and the superb editing, aided by the use of multiple cameras during a shot, are things that you'd expect to see in a feature with a large budget. This, paired with excellent black & white photography and a thrilling plot, has turned the movie into a classic instead of a cult fad.

Russ Meyer has brought a plethora of tales that feature femme fatales, vixens, and unapologetic ladies, but none are as flawless as Faster, Pussycat! Aside from being ahead of its time by approaching women as forces to be reckoned with—not trampled on—Meyer employed various techniques that were rarely used in low budget film. The frame composition in the action sequences and the superb editing, aided by the use of multiple cameras during a shot, are things that you'd expect to see in a feature with a large budget. This, paired with excellent black & white photography and a thrilling plot, has turned the movie into a classic instead of a cult fad.

The opening sequence pretty much forces you, in a somewhat silly way, to go into the movie expecting to see women who aren't of the norm. A narrator informs the audience that there is a new breed of woman—vicious, unrelenting beasts; animals in a shell of soft skin. The voice-over states that in these “new times,” one can never know what to expect of a woman, and that those who you need to watch out for could be anyone: secretaries, nurses, or even go-go dancers.

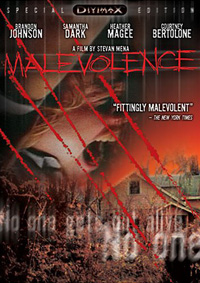

Malevolence

One of the most remarkable things about the movie Malevolence is how much it authentically captures the vibe and spirit of the early '80s “slasher” films it tries to homage with such reverence. In fact, after I initially saw it in its limited theatrical run back in 2004, I immediately jumped online to confirm that it was in fact a recently made feature film and not a long lost gem from the '80s that was only just then surfacing. Sure enough, upon a bit more research, I discovered that the goal of writer/director Stevan Mena was to emulate the horror films that had had such a profound impact on him growing up. And in that regard, he completely succeeded.

One of the most remarkable things about the movie Malevolence is how much it authentically captures the vibe and spirit of the early '80s “slasher” films it tries to homage with such reverence. In fact, after I initially saw it in its limited theatrical run back in 2004, I immediately jumped online to confirm that it was in fact a recently made feature film and not a long lost gem from the '80s that was only just then surfacing. Sure enough, upon a bit more research, I discovered that the goal of writer/director Stevan Mena was to emulate the horror films that had had such a profound impact on him growing up. And in that regard, he completely succeeded.

Malevolence opens with the kidnapping of Martin Bristol, a 6-year old boy from Pennsylvania who is forced to watch the evil deeds of his deranged captor, serial killer Graham Sutter. The film then cuts ahead 10 years later where we’re introduced to Julian (Brandon Johnson) and Marylin (Heather Magee) who along with Marylin’s brother Max (Keith Chambers) and Kurt (Richard Glover) are planning a daytime bank robbery. When things don’t go according to plan and the robbery is completely botched, the criminals flee with 2 hostages to their rendezvous point out in the countryside of Pennsylvania, just next to the old Sutter place and meat & poultry slaughterhouse. When they venture out towards the Sutter property, they inadvertently garner the attention of the long dormant killer at the house and uncover the horrors that have been going on there for over a decade. From then on, it’s just a matter of trying to survive the night.

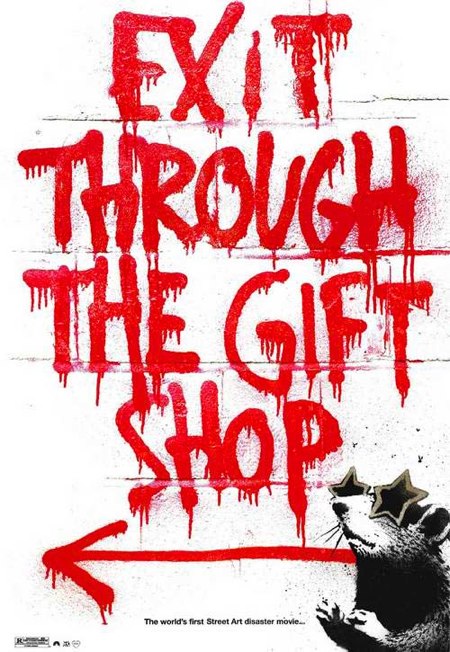

Exit Through the Gift Shop

Most of the talk surrounding Exit Through the Gift Shop was regarding whether it was a hoax or all real. But what was lost in the hoopla was what an incredibly entertaining and utterly fascinating film this documentary-within-a-

Most of the talk surrounding Exit Through the Gift Shop was regarding whether it was a hoax or all real. But what was lost in the hoopla was what an incredibly entertaining and utterly fascinating film this documentary-within-a-

Part conman, part art enthusiast, Guetta is like a bloated Pepe Le Pew. He has a bunch of kids and owns a Melrose vintage clothing store, and he constantly has a camera filming every aspect of his life. While visiting France he begins filming his cousin, a famous graffiti artist known as Invader. So begins an obsession for Guetta. Back in Hollywood he hooks up with another famous artist, Shepard Fairey (who later would become famous for his Obama “Hope” posters) and then meets loads more. He goes with them and takes part in their illegal night painting activities. When the legendary Bansky (whose real identity has never been revealed) comes to town, Guetta becomes his wingman and films all of his illegal art installations. Guetta then travels with him to London and back to LA where he serves as lookout for a stunt Banksy pulls in Disneyland. Eventually Bansky gives him the assignment to finally take all that footage and edit it into a film about street art. But what he puts together, a hodgepodge of images he calls Life Remote Control, it’s a total unwatchable mess.

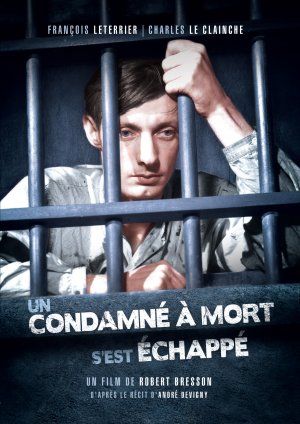

A Man Escaped

What do you think of when you hear the term French New Wave? Do you think of Francois Truffaut's The 400 Blows or Breathless, Jean-Luc Godard's first feature film? Surely the majority of those who adore the movement and acknowledge its influences believe that Truffaut, and in some circles, Godard, were the inventors of the French New Wave. Not to spit in anyone's soup, but I'd argue against those claims using this film alone. The attractiveness of a film like The 400 Blows comes from its simplicity and the relation of the film to the director. Of course there's the auteur theory mixed in and Truffaut did write the film, but the most important aspect of it is the director’s relation to story and how well its messages were relayed based on that relationship. The 400 Blows is an autobiographical tale that stems from Truffaut's boyhood, and therefore no-one else could have made it work except him. In that sense, it resembles art more than entertainment because of the personal aspect and a story about societal detachment, which many people can relate to. But he wasn't the first to make such a film. Robert Bresson, one of my favorite directors, did the same thing these directors did, only first. A Man Escaped is about a French POW, and in reality Bresson spent time as a POW in Germany before becoming a screenwriter and director.

What do you think of when you hear the term French New Wave? Do you think of Francois Truffaut's The 400 Blows or Breathless, Jean-Luc Godard's first feature film? Surely the majority of those who adore the movement and acknowledge its influences believe that Truffaut, and in some circles, Godard, were the inventors of the French New Wave. Not to spit in anyone's soup, but I'd argue against those claims using this film alone. The attractiveness of a film like The 400 Blows comes from its simplicity and the relation of the film to the director. Of course there's the auteur theory mixed in and Truffaut did write the film, but the most important aspect of it is the director’s relation to story and how well its messages were relayed based on that relationship. The 400 Blows is an autobiographical tale that stems from Truffaut's boyhood, and therefore no-one else could have made it work except him. In that sense, it resembles art more than entertainment because of the personal aspect and a story about societal detachment, which many people can relate to. But he wasn't the first to make such a film. Robert Bresson, one of my favorite directors, did the same thing these directors did, only first. A Man Escaped is about a French POW, and in reality Bresson spent time as a POW in Germany before becoming a screenwriter and director.

The film opens with a note from Bresson that simply states, “This is a true story.” Nowhere does it imply that it is his story or something similar, just that it's not a fabrication. Followed by this is the image of a stone and etched into it is a short passage paying respects to 7,000 Frenchmen who were killed by Nazis and Nazi allies. Next we see a simple sequence of a handsome man riding in a car. The camera is focused on his hands, which slowly creep towards the door handle of the moving vehicle. As the camera pulls away, we see two men handcuffed beside him and can make out “SS” uniforms on the driver and front passenger. We see the man hesitate and consider leaping from the car, and eventually he musters up the courage to do so. Within seconds he's returned and pistol-whipped as punishment, but they keep him alive and put him in prison. This opening sequence sets the stage for a story that has enough suspense to stand up to Hitchcock and enough pathos and realism to be considered the true beginning of French New Wave.

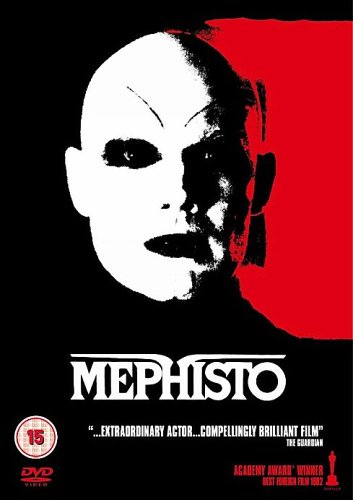

Mephisto

Mephistopheles, or Mephisto, is a character from German folklore that is an evil demon, or more suitably, the devil. The demon element to the character appears in the German legend of Faust in which an ambitious man makes a pact with the devil in order to obtain ultimate power and great success. This legend plays a huge part in this film, though the story is also heavily based on Klaus Mann's novel Mephisto and the life of Gustaf Grünfgens, the theater manager, actor, and director who was revered as one of the best of his time. Grünfgens's career prior to the rise of Hitler and the Nazi regime was fruitful, and being a sympathizer with the Third Reich certainly helped him prosper and continue to do so after the fall of Hitler. Grünfgens was also bipolar, for lack of a better word, when it came to his morals, sexuality, and political affiliations. Knowing this information may or may not take away some of the magic of the film. However, Klaus Maria Brandauer's performance is more than a stormy reincarnation of Grünfgens and the Faustian legend. It shows the upside of having an egoist portray a person who is so sure of themselves that they deny their affiliation with true evil.

Mephistopheles, or Mephisto, is a character from German folklore that is an evil demon, or more suitably, the devil. The demon element to the character appears in the German legend of Faust in which an ambitious man makes a pact with the devil in order to obtain ultimate power and great success. This legend plays a huge part in this film, though the story is also heavily based on Klaus Mann's novel Mephisto and the life of Gustaf Grünfgens, the theater manager, actor, and director who was revered as one of the best of his time. Grünfgens's career prior to the rise of Hitler and the Nazi regime was fruitful, and being a sympathizer with the Third Reich certainly helped him prosper and continue to do so after the fall of Hitler. Grünfgens was also bipolar, for lack of a better word, when it came to his morals, sexuality, and political affiliations. Knowing this information may or may not take away some of the magic of the film. However, Klaus Maria Brandauer's performance is more than a stormy reincarnation of Grünfgens and the Faustian legend. It shows the upside of having an egoist portray a person who is so sure of themselves that they deny their affiliation with true evil.

br /> Brandauer plays Hendrik Hoefgen, an up-and-coming actor and theater director in Hamburg, Germany. In the beginning, Hoefgen wanted to take the stiffness from the stage by eliminating the distance between audience and performer. His aim was to create a new theater, full of vibrant and charismatic characters who could move audiences in a way that had never been done before. He also romanticized the idea of bohemian theater—one in which miners and laborers could feel comfortable and included. This led to his passionate pursuit of a revolution through theater, though there was little to revolt against in the beginning.

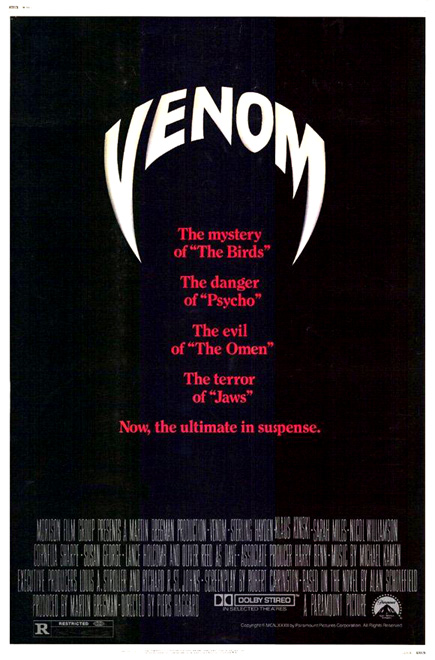

Venom

In terms of B-Movie all-star casts this crazy British flickVenom can’t be beat. All working at their highest ham level, you have the insane German method madman Klaus Kinski (Aguirre: The Wrath of God), and then there’s the American Sterling Hayden who in the fifties was a total stiff playing a lot of tough guys but then reinvented himself in the seventies as an solid character actor (The Godfather). Also on board is the great British actor Oliver Reed (The Devils) who was equally famous for his up and down career as he was for his drunken on-set behavior. Adding some more class to the cast is another terrific British actor Nicol Williamson who, other then his great performance as Merlin in Excalibur, never quite had the career he should’ve had. Rounding out the cast in the female roles, there’s swinging sixties British starlet Sarah Miles (Blow-Up), fashion-model-turned-actress Cornelia Sharpe (Serpico) and the always sexy Susan George (Straw Dogs). For a low budget flick Irwin Allen couldn’t have assembled a cooler line-up.

In terms of B-Movie all-star casts this crazy British flickVenom can’t be beat. All working at their highest ham level, you have the insane German method madman Klaus Kinski (Aguirre: The Wrath of God), and then there’s the American Sterling Hayden who in the fifties was a total stiff playing a lot of tough guys but then reinvented himself in the seventies as an solid character actor (The Godfather). Also on board is the great British actor Oliver Reed (The Devils) who was equally famous for his up and down career as he was for his drunken on-set behavior. Adding some more class to the cast is another terrific British actor Nicol Williamson who, other then his great performance as Merlin in Excalibur, never quite had the career he should’ve had. Rounding out the cast in the female roles, there’s swinging sixties British starlet Sarah Miles (Blow-Up), fashion-model-turned-actress Cornelia Sharpe (Serpico) and the always sexy Susan George (Straw Dogs). For a low budget flick Irwin Allen couldn’t have assembled a cooler line-up.

Director Piers Haggard was fresh off directing Peter Sellers’s final film, a horrible wreck called The Fiendish Plot of Dr. Fu Manchu. He replaced the American director Tobe Hooper (Texas Chainsaw Massacre) who was fired for creative reasons days into filming Venom. What’s ironic is that a few years later Hooper would make one of the craziest British genre mash-ups of all time, the zombie/alien/vampire flick Life Force. In the meantime Venom still stands as another solid genre mash-up; it’s both a kidnapping thriller and a snake-on-the-loose flick, and it does both very well.

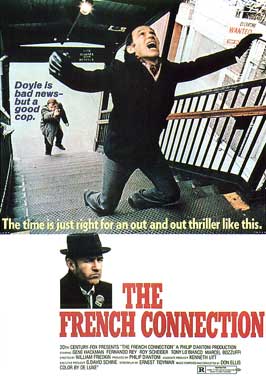

The French Connection

Besides still being the quintessential “cop vs. international drug traffickers” flick and winning a boatload of Oscars, The French Connection also helped to establish director William Friedkin and star Gene Hackman as major talents. Hackman would hold onto his status for decades while Friedkin’s career would continue to rise before a major fizzle out.

Besides still being the quintessential “cop vs. international drug traffickers” flick and winning a boatload of Oscars, The French Connection also helped to establish director William Friedkin and star Gene Hackman as major talents. Hackman would hold onto his status for decades while Friedkin’s career would continue to rise before a major fizzle out.

In still maybe his greatest role, Hackman plays the doggedly determined New York narcotics detective Jimmy “Popeye” Doyle. Even when off work having drinks (and like most movie cops he has lots of them) he’s putting a tail on potential dope-peddling mobster creeps. He plays his hunches, which have paid off before, but more often than not have gotten him in trouble or made him look foolish. He’s a new kind of film cop—he’s as hard-boiled as Bogart but less heroic and certainly less likable. With his overt racism and lack of ethics, he’s all about busting the bad guys at any cost. With his slightly more rational sidekick Russo (Roy Scheider, in the first of his many cop roles in the ‘70s), they have a natural inclination to fight their bosses as much as the criminals. (Interestingly this was the same year that Dirty Harry was released, another famous rebel-cop.)

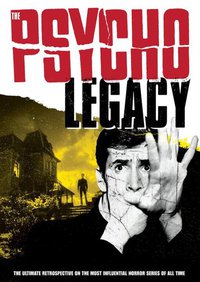

The Psycho Legacy

With so many books and documentaries made over the decades covering every aspect of Alfred Hitchcock’s amazing career and more specifically his masterpiece Psycho, what more can possibly be said about the subject? Director Robert V. Galluzzo manages to find a new and surprisingly fresh angle— instead of mulling over the influences on Hitchcock, we are reminded of the massive influence Psycho had. With an interesting group of talking heads, all obvious enthusiasts, they first contemplate the mythology that Psycho brought to cinema, but quickly they get to what makes the documentary most unique which is the study of the Psycho film sequels that sprung up some years later. Though not as commercially successful as many current horror film series, Galluzzo’s posse does manage to convince that they are worth a look.

With so many books and documentaries made over the decades covering every aspect of Alfred Hitchcock’s amazing career and more specifically his masterpiece Psycho, what more can possibly be said about the subject? Director Robert V. Galluzzo manages to find a new and surprisingly fresh angle— instead of mulling over the influences on Hitchcock, we are reminded of the massive influence Psycho had. With an interesting group of talking heads, all obvious enthusiasts, they first contemplate the mythology that Psycho brought to cinema, but quickly they get to what makes the documentary most unique which is the study of the Psycho film sequels that sprung up some years later. Though not as commercially successful as many current horror film series, Galluzzo’s posse does manage to convince that they are worth a look.

Though the documentary only uses quick muted clips from the films, the stills and the talking heads are engaging enough that you may not even notice. It mentions early on, briefly, that William Castle spent a decade trying to rip-off Psycho (Straight-Jacket, Homicidal, etc.), but the dozens of French thrillers and Italian horror flicks that were directly influenced by Hitchcock are ignored. Hell, if you want to talk about Psycho’s legacy (and Hitchcock’s) Brian De Palma’s had a whole career doing bad Hitchcock (until later when he discovered other genres to steal from). The Psycho Legacy also avoids Gus Van Sant’s pointless scene-for-scene remake and the short-lived Bud Court TV Series The Bates Motel. No, the Psycho legacy these guys are itching to rap about are the three “sequels.”

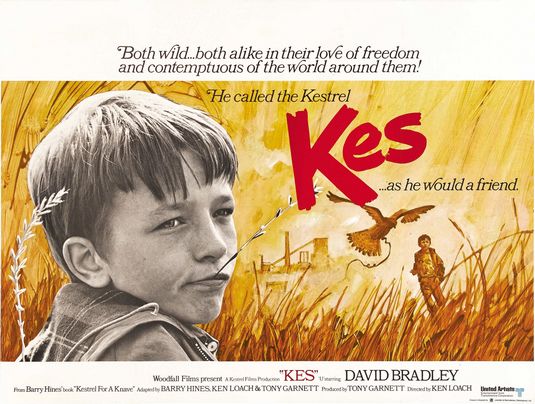

Kes

For a long time the belief held between parents and educators alike was fairly simple: “spare the rod, spoil the child.” In our modern world, at least in the West, those who work with and/or rear children seem to be desperately trying to find some common ground when it comes to disciplinary matters. And when each generation reaches adulthood, or more appropriately middle age, the majority looks at the youth around them as a mass of spoiled delinquents. They refuse to understand the new pastimes, music and general attitudes toward life and responsibilities. It makes you wonder if there is ever any truth to this popular argument. Do the youth of every nation grow more reckless across generations, or are they simply misunderstood?

For a long time the belief held between parents and educators alike was fairly simple: “spare the rod, spoil the child.” In our modern world, at least in the West, those who work with and/or rear children seem to be desperately trying to find some common ground when it comes to disciplinary matters. And when each generation reaches adulthood, or more appropriately middle age, the majority looks at the youth around them as a mass of spoiled delinquents. They refuse to understand the new pastimes, music and general attitudes toward life and responsibilities. It makes you wonder if there is ever any truth to this popular argument. Do the youth of every nation grow more reckless across generations, or are they simply misunderstood?

Ken Loach tries to shed some light on this concept with his adaptation of Barry Hines's novel, A Kestrel for a Knave. In the film we follow Billy Caspar (David Bradley), an adolescent marked as the village idiot who turns out to be anything but. He enjoys taking it easy; exemplifying what behaviorists might consider to be a relaxed personality. He's the local paperboy in his village, but instead of building a good work ethic he reads the cartoon section of the paper over a pint of stolen milk when he should be doing his rounds. His impulse to steal seems somewhat merited by his impoverished existence within a harsh class system, and the fact that he mainly steals food and literature. He doesn't shower, nor does he wear underpants. He lives with his single mother (Lynne Perrie) and has to share a small bed with his crass older brother Jud (Freddie Fletcher) who works in the mines and bullies his family. At school he spends most his time daydreaming and falling asleep from exhaustion. He's an easy target to be made an example of by his teachers who refuse to tolerate his devil-may-care attitude. When not being hit with a ruler or mocked by his teachers in class for his presumably insolent behavior, he's bullied by a group of boys who he used to hang with.

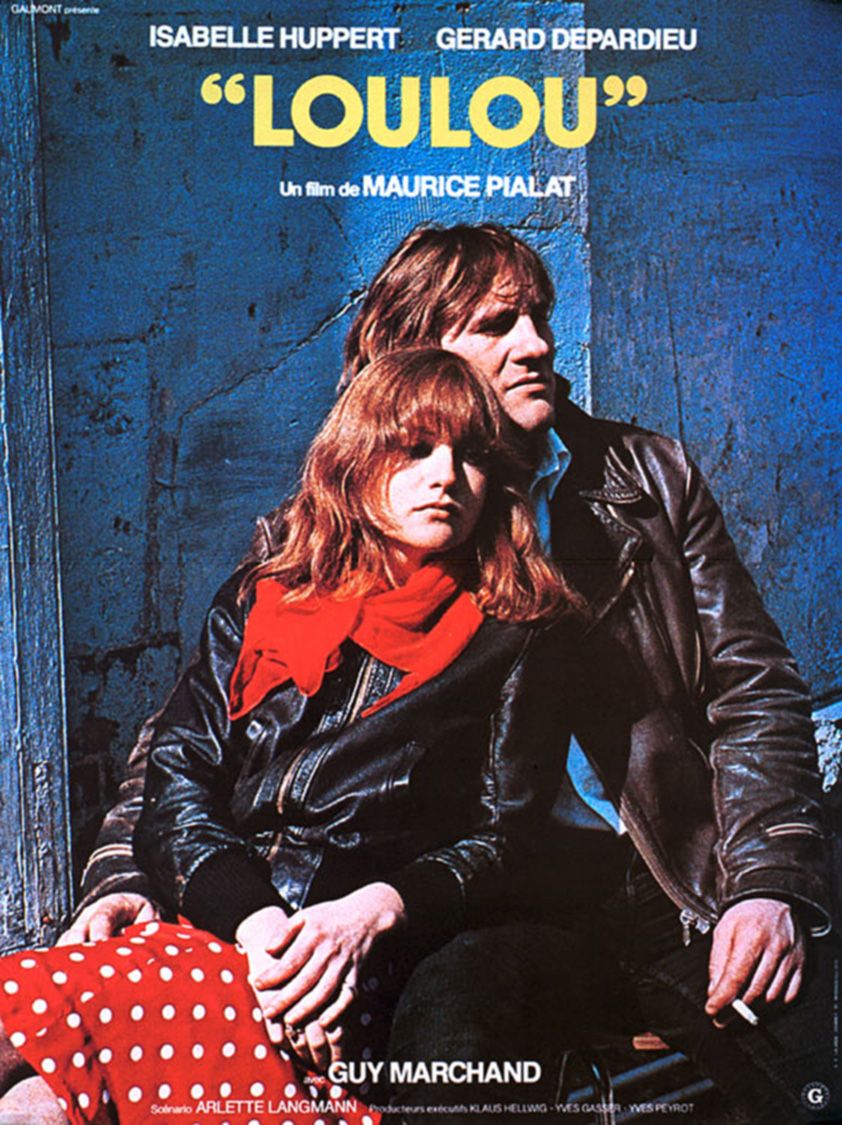

Loulou

Some of the most daring romantic dramas are ones in which the lovers in question are total opposites, or with each other for reasons that don't have anything to do with love. While anticipating their breakup throughout the film's entirety, you take on the role of a mediator in your imagination. You notice the flaws in each lover, and how those very flaws attract the other person. You take sides in their disputes depending on whoever seems to be more tolerable. It's precisely this kind of intrusion—the ability to analyze and compare someone's circumstances with your own—that makes the story work and keeps you invested.

Some of the most daring romantic dramas are ones in which the lovers in question are total opposites, or with each other for reasons that don't have anything to do with love. While anticipating their breakup throughout the film's entirety, you take on the role of a mediator in your imagination. You notice the flaws in each lover, and how those very flaws attract the other person. You take sides in their disputes depending on whoever seems to be more tolerable. It's precisely this kind of intrusion—the ability to analyze and compare someone's circumstances with your own—that makes the story work and keeps you invested.

In the film Gerard Depardieu plays Loulou, a penniless playboy and ex-con who prides himself on breaking girls' hearts by flaunting his unwillingness to be monogamous. His whipped ex-girlfriend Dominique follows him around like a sick puppy, giving us the perfect illustration of his effect on women and their willingness to be spat on while in or out of a relationship with him. At a discotheque he falls under the bewitching spell of Nelly (Isabelle Huppert), a married woman from an upscale background who's been followed to the club by her husband Andre (Guy Marchand). As he watches her dance and flirt with Loulou, he comes to the conclusion that she needs to be outed as a tramp in public. Following his verbal and physical abuse, Nelly decides to start her first extramarital affair with Loulou.