Movies We Like

Handpicked By The Amoeba Staff

Films selected and reviewed by discerning movie buffs, television junkies, and documentary diehards (a.k.a. our staff).

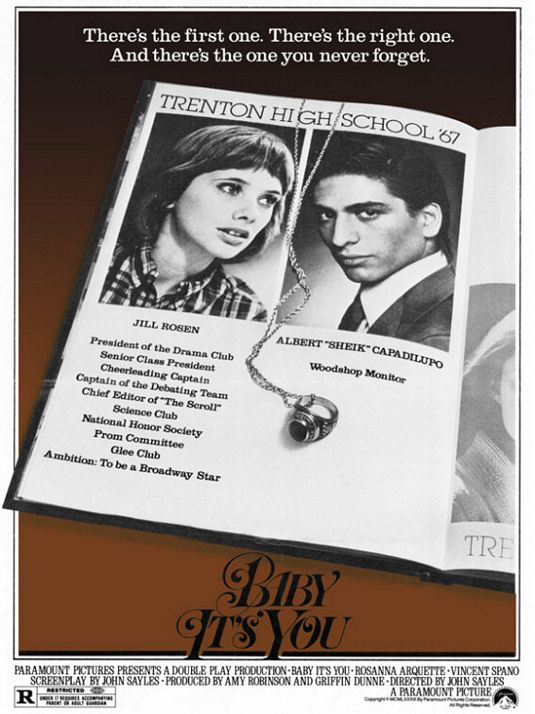

Baby It's You

In 1966, Trenton New Jersey still seemed stuck in the cross hairs of the ‘50s and ‘60s. The British Invasion was in full effect and white kids were now listing to black music but the era of Frank Sinatra still held sway with some. For high school senior Jill Rosen (Rosanna Arquette) it’s a particularly confusing era; an aspiring actress, she is trying to embrace the times, find her own voice, and gain her independence, but when she is wooed by and then eventually gets in a relationship with an odd, new, rebelliously hunky greaser at school, known as Sheik (Vincent Spano), her place in the world, her values and aspirations, are challenged. Even after Jill goes away to college and her experiences are expanded, he still lingers in her mind as a representation of her past, a life she can’t quite outgrow.

In 1966, Trenton New Jersey still seemed stuck in the cross hairs of the ‘50s and ‘60s. The British Invasion was in full effect and white kids were now listing to black music but the era of Frank Sinatra still held sway with some. For high school senior Jill Rosen (Rosanna Arquette) it’s a particularly confusing era; an aspiring actress, she is trying to embrace the times, find her own voice, and gain her independence, but when she is wooed by and then eventually gets in a relationship with an odd, new, rebelliously hunky greaser at school, known as Sheik (Vincent Spano), her place in the world, her values and aspirations, are challenged. Even after Jill goes away to college and her experiences are expanded, he still lingers in her mind as a representation of her past, a life she can’t quite outgrow.

Director John Sayles had been a wonderful screenwriter of campy B-movies (Piranha, Alligator and The Howling), but as a director he made a name for himself with his deeply personal, character-driven independent films Return of the Secaucus Seven (which The Big Chill has been accused of ripping-off) and Lianna. Though Baby It’s You brought the quality of his style up a few notches, it was still a very small-budget flick. The New Jersey connection explains why the film’s soundtrack is loaded with early Bruce Springsteen music, which unfortunately now gives the film a ‘70s vibe; but other than that the 1966 period detail is perfect, not just in the design but the characters’ emotional makeup.

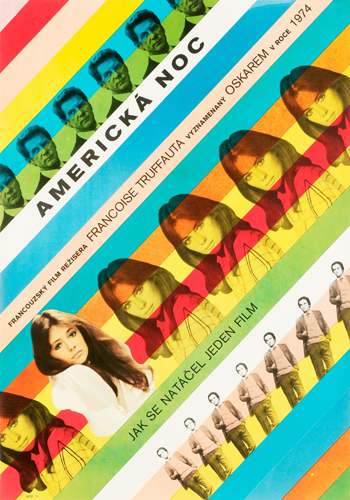

Day for Night

"We meet, we work together, we love each other, and then...pfft...as soon as we grasp something, it's gone."

"We meet, we work together, we love each other, and then...pfft...as soon as we grasp something, it's gone."

— The aging actress Severine’s (played by Italian starlet Valentia Cortese) astute lament on the intangible nature of filmmaking resounds the yearning romance of all art in Francois Truffaut’s 1973 film, Day for Night.

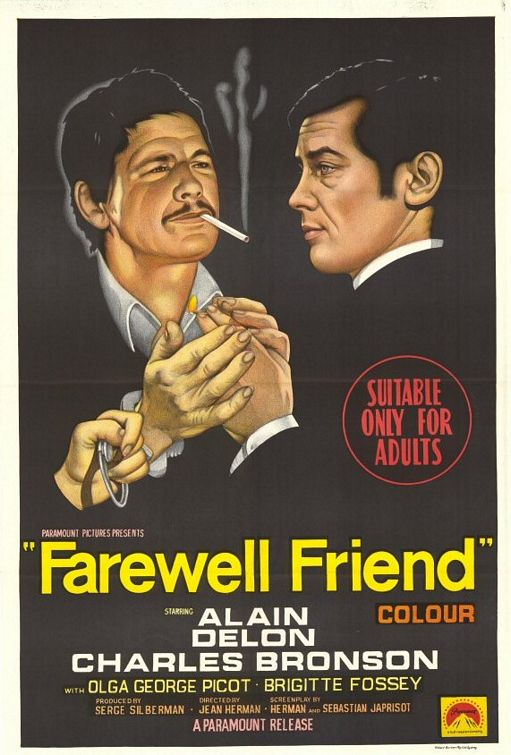

Farewell Friend

Re-released in the U.S. as Honor Among Thieves, Farewell Friend is essentially a buddy flick masked in a slow-paced action movie. There’s the quintessential rift between two rogues, one extroverted and overly talkative and the other introverted and dependant on one-liners while desperately trying to keep the former at arm's length throughout the majority of the film. The introvert in this film is Dino Barran (Alain Delon), a military doctor who has just been discharged. Oddly enough, the extrovert is his cohort Franz Propp (Charles Bronson), a mercenary who has also been discharged and once worked with Barran in the French Foreign Legion.

Re-released in the U.S. as Honor Among Thieves, Farewell Friend is essentially a buddy flick masked in a slow-paced action movie. There’s the quintessential rift between two rogues, one extroverted and overly talkative and the other introverted and dependant on one-liners while desperately trying to keep the former at arm's length throughout the majority of the film. The introvert in this film is Dino Barran (Alain Delon), a military doctor who has just been discharged. Oddly enough, the extrovert is his cohort Franz Propp (Charles Bronson), a mercenary who has also been discharged and once worked with Barran in the French Foreign Legion.

Now that they’re free to go about their lives, Barran can’t wait to shed his uniform and avoid anyone and everyone from the past while Propp wants to be chummy with Barran and reminisce about old times. And as buddy films usually will have it, the two end up sharing a small slice of life regardless of their attitudes towards each other, only to realize towards the end that the other isn’t so bad. Think Planes, Trains & Automobiles with muscular soldiers who’ve been discharged and find themselves heading for the same turkey.

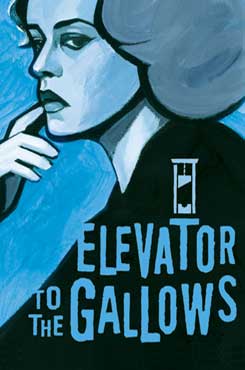

Elevator to the Gallows

Combining the splendid black and white photography of Henri Decaë, the magnetic force of Jeanne Moreau, and a superb jazz score by Miles Davis, Louis Malle’s directorial debut is incomparable in terms of mood and style.

Combining the splendid black and white photography of Henri Decaë, the magnetic force of Jeanne Moreau, and a superb jazz score by Miles Davis, Louis Malle’s directorial debut is incomparable in terms of mood and style.

The film was poorly received by critics but has since been deemed a masterpiece, both in terms of direction and pre-new wave modernity. The score by Miles Davis, accompanied with then unknown players and bop drummer Kenny Clarke, would fuel Davis to take on certain conventions within jazz—most notably, the kind heard through his album Kind of Blue that followed two years after the film’s release. Decaë’s work would also become prominent in the works of several new wave directors, specifically Truffaut and Chabrol. Perhaps the most interesting quality to the film is the fact that it is a rarity from Malle. It marks the first and only time that the director tried his hand at noir, or worked so tightly in the confines of a genre. As it goes with films like Riffifi and Le Cercle Rouge, the criminal aspects of it are somewhat downplayed by a wonderful cast and outstanding photography.

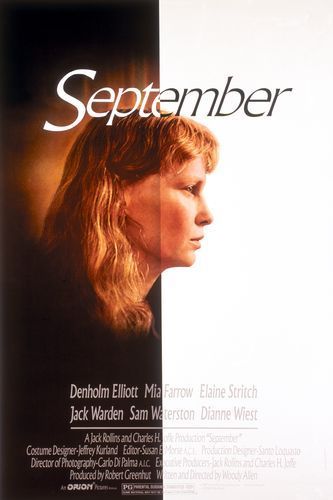

September

“It’s hell gettin’ older, especially when you feel 21 inside.”

“It’s hell gettin’ older, especially when you feel 21 inside.”

— A sobering reflection made by the aging Diane, brashly played by the vibrant, and still very alive at 86, Elaine Stritch, in Woody Allen’s 1987 drama, September.

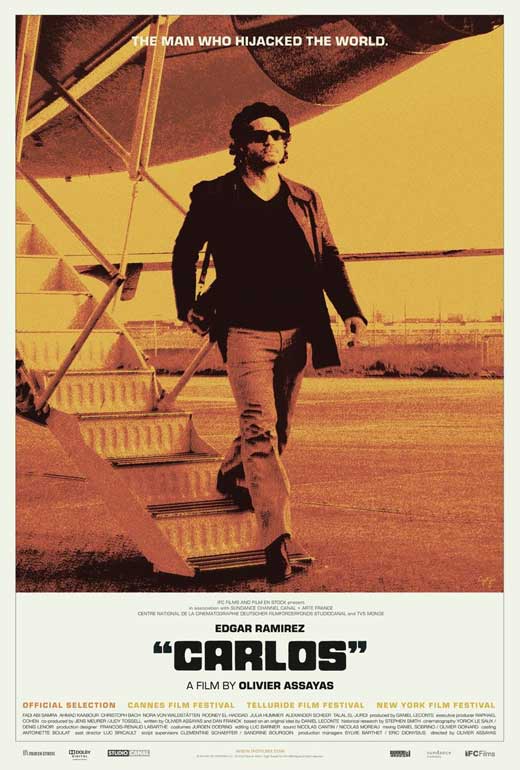

Carlos

The last decades haven’t been that great for real-life political radicalism, but in the movies it’s been extraordinary: Baader Meinhof Complex, Munich, Che, the cartoonish Eight Miles High, and now, Olivier Assayas’s extraordinary bio Carlos (epic is an understatement). Not since the glory days of The Battle of Algiers, State Of Siege, and Z have political terror cells been so damn entertaining. Even more thanV for Vendetta, Carlos is one of the giddiest pro-terrorism flicks ever made. Originally made for French television, the five-hour-plus Carlos has been released in theaters at different lengths; but The Criterion Collection DVD includes the three episodes, at their original length, spread over three discs (with a fourth disc containing an excellent French documentary that helps to fill in the holes). Carlos is so dense with history and international period detail that seeing those above-mentioned films (which have a number of crossover characters and references in Carlos) definitely helps make the film easier to follow. But that’s not to say you have to be a history major to appreciate Carlos; it’s so riveting and Carlos, the character, is so fascinating that just committing to it proves amazingly rewarding.

The last decades haven’t been that great for real-life political radicalism, but in the movies it’s been extraordinary: Baader Meinhof Complex, Munich, Che, the cartoonish Eight Miles High, and now, Olivier Assayas’s extraordinary bio Carlos (epic is an understatement). Not since the glory days of The Battle of Algiers, State Of Siege, and Z have political terror cells been so damn entertaining. Even more thanV for Vendetta, Carlos is one of the giddiest pro-terrorism flicks ever made. Originally made for French television, the five-hour-plus Carlos has been released in theaters at different lengths; but The Criterion Collection DVD includes the three episodes, at their original length, spread over three discs (with a fourth disc containing an excellent French documentary that helps to fill in the holes). Carlos is so dense with history and international period detail that seeing those above-mentioned films (which have a number of crossover characters and references in Carlos) definitely helps make the film easier to follow. But that’s not to say you have to be a history major to appreciate Carlos; it’s so riveting and Carlos, the character, is so fascinating that just committing to it proves amazingly rewarding.

In Episode One we meet Ilich Ramírez Sánchez, AKA Carlos (Edgar Ramirez), a young Venezuelan man who claims to be a Marxist committed to the anti-imperialism and pro-Palestinian causes (though not always pro Arab). We get no back story; the film opens with Carlos already established in political terrorist circles. He’s no modern day religious zealot; he seems to just be a fearless, hunky, suave playboy who is socially connected to every radical group from Europe to the Middle East. While seducing a woman he plays with his guns and has her orally pleasure a grenade while telling her “weapons are an extension of my body.” He smokes and drinks; at first the operatives above him treat him like a kid, but as his criminal star rises they begin to fear him. He’s a would-be assassin, with more than nine lives under his belt. But unlike The Jackal in The Day of the Jackal he’s not in it for the money; he’s clumsy and his plots are not as well planned out. Though Carlos and his comrades kill a lot of people in many countries they often get killed a lot themselves. Many women come and go throughout his life; some join his struggle, while others are just lovers. Episode One ends on a suspenseful note as Carlos and a makeshift little international militant group are preparing to attack OPEC headquarters in Vienna.

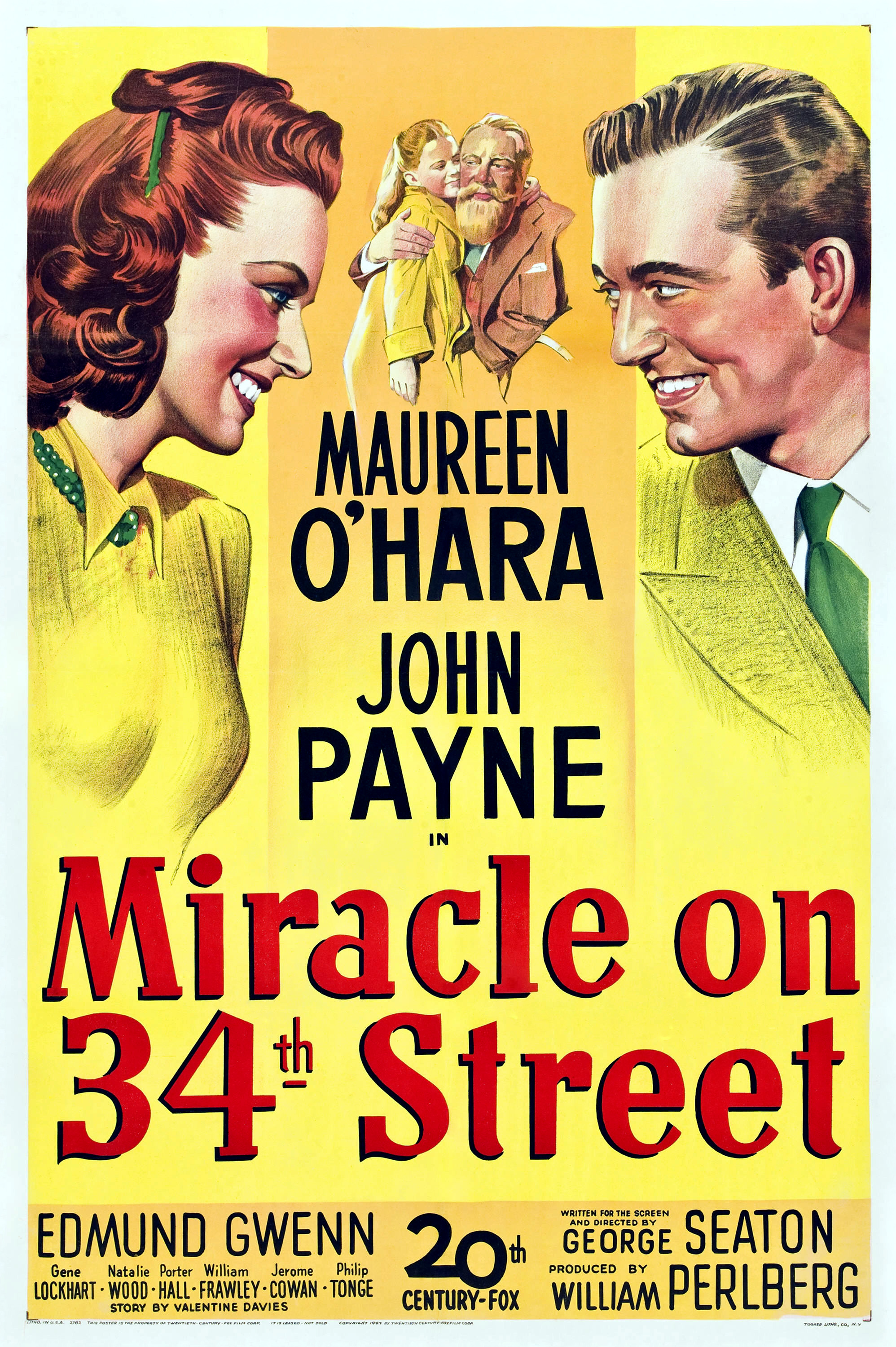

Miracle on 34th Street

No other film in history has been able to capture the spirit of Christmas and toss cinders on the commercialism that the holiday has come to represent quite like Miracle on Thirty-Fourth Street. At 60-something-years-old, the film is still just as relevant, funny, and, ultimately, moving as it ever was. Like How the Grinch Stole Christmas (the original animated version), It’s a Wonderful Life,and the more recent A Christmas Story, Miracle on Thirty-Fourth Street has become standard, even compulsive, viewing during the holiday season. Today’s kids may think that Christmas is some kind of video game or a season to shop and spend money, but Miracle on Thirty-Fourth Street has reminded generations what it’s supposed to be about. As Mr. Kringle says in the film, “Christmas isn’t just a day; it’s a frame of mind.”

No other film in history has been able to capture the spirit of Christmas and toss cinders on the commercialism that the holiday has come to represent quite like Miracle on Thirty-Fourth Street. At 60-something-years-old, the film is still just as relevant, funny, and, ultimately, moving as it ever was. Like How the Grinch Stole Christmas (the original animated version), It’s a Wonderful Life,and the more recent A Christmas Story, Miracle on Thirty-Fourth Street has become standard, even compulsive, viewing during the holiday season. Today’s kids may think that Christmas is some kind of video game or a season to shop and spend money, but Miracle on Thirty-Fourth Street has reminded generations what it’s supposed to be about. As Mr. Kringle says in the film, “Christmas isn’t just a day; it’s a frame of mind.”

The beautiful but icy Doris Walker (Maureen O’Hara) is a cynical single mom who works for the glamorous Macy’s Department Store in New York City. While handling the big Thanksgiving Day Parade she pulls a bearded old man (Edmund Gwenn) off the street to play Santa Claus. The twist is he actually claims to be the jolly toy maker and even calls himself Kris Kringle. The good-natured, but possibly delusional, old coot is so convincing Macy’s hires him to be their full-time in-store Santa. Meanwhile, Doris’s daughter, Susan (Natalie Wood), is her mom’s mini-me, with equal disdain for childish things like make-believe. But when she befriends her do-gooder neighbor, a bachelor lawyer with the unfortunate name of Fred Gailey (John Payne), he encourages her to start to act like a kid and gets Doris to instantly open her heart to romance. All three befriend Kris, while he and Fred try to loosen up the two uptight females. Little Susan is taken aback when she see Kris speak Dutch to a peewee foreign girl, giving her the idea that maybe this guy is the real deal.

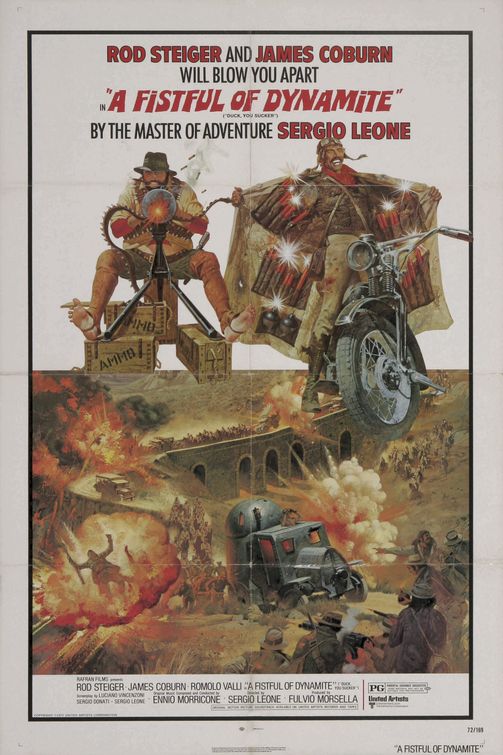

Duck, You Sucker (AKA A Fistful of Dynamite)

If Once Upon a Time in the West was Sergio Leone’s North by Northwest or Rear Window, then Duck, You Sucker (AKA A Fistful of Dynamite) was his Vertigo. It was a misunderstood film in its day; fans were startled by the director breaking from his formula and actually trying to say something. But like Hitchcock, what he had to say also didn’t satisfy what audiences wanted to hear, and the pace didn’t give them the thrills they were used to. With Duck, You Sucker, Leone was working on a potentially bigger canvas than Once Upon a Time in the West. Working with his biggest budget yet meant that Leone did have to concede his casting choices to the studio. Rod Steiger and James Coburn were hardly Leone’s first choices to play the leads, but United Artists considered both big stars while Jason Robards wasn’t bankable enough and Clint Eastwood was no longer available.

If Once Upon a Time in the West was Sergio Leone’s North by Northwest or Rear Window, then Duck, You Sucker (AKA A Fistful of Dynamite) was his Vertigo. It was a misunderstood film in its day; fans were startled by the director breaking from his formula and actually trying to say something. But like Hitchcock, what he had to say also didn’t satisfy what audiences wanted to hear, and the pace didn’t give them the thrills they were used to. With Duck, You Sucker, Leone was working on a potentially bigger canvas than Once Upon a Time in the West. Working with his biggest budget yet meant that Leone did have to concede his casting choices to the studio. Rod Steiger and James Coburn were hardly Leone’s first choices to play the leads, but United Artists considered both big stars while Jason Robards wasn’t bankable enough and Clint Eastwood was no longer available.

Throughout Leone’s Eastwood “Man with No Name” trilogy, each film was made back-to-back-to-back (A Fistful of Dollars, For a Few Dollars More and The Good, the Bad & the Ugly) and each got more progressively ambitious in both scope and ambition as their popularity grew. Finally, the director peaked with his follow-up, Once Upon a Time in the West, an accumulation of all the ideas he had been building towards and both the ultimate post-modern western and one of the true film masterpieces of the 1960s. He finally took a break (three years) before returning to the screen with the eccentric Duck, You Sucker (afterwards he would take an even longer break, not being a credited director for 11 years). In some territories the film was titled Once Upon a time in the Revolution or A Fistful of Dynamite but it would not fully fit with his first four flicks (we all tend to ignore his unrecognizable debut The Colossus Of Rhodes in ’61). Everything about this new film felt slightly tweaked. Its tones moved from comic to dramatic to sentimental to tragic to cartoony much less gracefully than in his past work. The setting moved south to Mexico and the period moved up a couple decades. Where Once Upon a Time in the West had a deliberate pace, the strands perfectly came together and justified their speed, while at almost 160 minutes Duck, You Sucker sometimes just feels long and, worse, indulgent. But luckily that indulgence and the hint of a director slightly lost in his creation proves to be both fascinating and entertaining. And just as westerns had been reinvented in the ‘60s, the ‘70s saw another seismic shift where movies as diverse as Duck, You Sucker, El Topo, The Missouri Breaks, and, finally, Heaven’s Gate would help to kill the genre for a generation.

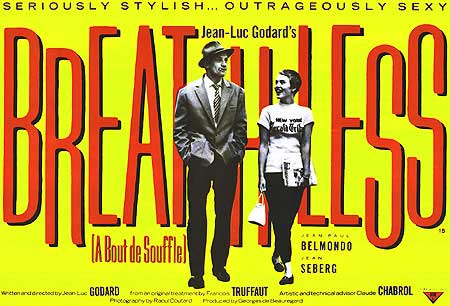

Breathless

It’s not an overstatement to say that Jean-Luc Godard’s noiry, crime-romance Breathless (À bout de souffle) may be one of the most important films of a very important film era—a game changer. For the film critic turned filmmaker, Breathless Godard’s first feature and it helped to define an exciting new cinema movement that was brewing among young cinephiles in France now known as The French New Wave. With its hand-held photography, jump cutting, improvised script, and natural lighting, it carefully broke many rules of formal cinema. Inspired by American crime films, mostly the B-movies that that generation of the French critics came to appreciate long before their American counterparts, it romanticized the underworld, without the moral lessons of so many similar American movies. The film also gives a shout-out to Jean-Pierre Melville’s Bob Le Flambeur, another film inspired by American Noirs. Playing the film’s lead, a small-time crook with a death wish, Breathless put actor Jean-Paul Belmondo on the map. His gripping and charismatic performance reeks of his influences, most notably Humphrey Bogart and Marlon Brando. Like so many filmmakers to come, from Martin Scorsese to Quentin Tarantino (who both cite Breathless as a major influence), Godard’s work, and Breathless in particular, was a tribute to the movies that came before that the director admired.

It’s not an overstatement to say that Jean-Luc Godard’s noiry, crime-romance Breathless (À bout de souffle) may be one of the most important films of a very important film era—a game changer. For the film critic turned filmmaker, Breathless Godard’s first feature and it helped to define an exciting new cinema movement that was brewing among young cinephiles in France now known as The French New Wave. With its hand-held photography, jump cutting, improvised script, and natural lighting, it carefully broke many rules of formal cinema. Inspired by American crime films, mostly the B-movies that that generation of the French critics came to appreciate long before their American counterparts, it romanticized the underworld, without the moral lessons of so many similar American movies. The film also gives a shout-out to Jean-Pierre Melville’s Bob Le Flambeur, another film inspired by American Noirs. Playing the film’s lead, a small-time crook with a death wish, Breathless put actor Jean-Paul Belmondo on the map. His gripping and charismatic performance reeks of his influences, most notably Humphrey Bogart and Marlon Brando. Like so many filmmakers to come, from Martin Scorsese to Quentin Tarantino (who both cite Breathless as a major influence), Godard’s work, and Breathless in particular, was a tribute to the movies that came before that the director admired.

After Michael (Belmondo) steals a car and then shoots a cop, he finds himself on the run. Still always playing it cool, he hides out in Paris with an American girl, Patricia (Jean Seberg), a New York Herald Tribune street vendor. Like the best of French couples they smoke a lot of cigarettes, have sex, and talk philosophically about themselves. She is in love with him, but he is selfish and utterly self-obsessed, as he makes Bogart-like faces in a mirror always trying to perfect his gangster persona. She knows he’s bad news but maybe that’s what makes her even more devoted. She may be a naive waif, but she’s also college bound; she’s not a simpleton like Sissy Spacek in Badlands, she just wants a classic bad-boy lover. Her love and her own need to survive eventually lead her to rat him out to the cops. In a long famous death scene he is shot and killed before falling breathless.

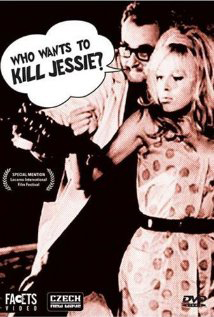

Who Wants to Kill Jessie?

Who Wants to Kill Jessie? is an underrated gem from a Czech New Wave director that hardly anybody has heard of. It plays on the conventions of comic strips, the mystery of dreams, and communist efforts in Czechoslovakia—with mad scientists who represent brainwashing.

Who Wants to Kill Jessie? is an underrated gem from a Czech New Wave director that hardly anybody has heard of. It plays on the conventions of comic strips, the mystery of dreams, and communist efforts in Czechoslovakia—with mad scientists who represent brainwashing.

Ruzenka (Dana Medricka) and Jindrich (Jiri Sovak) are a married couple who are both scientists. Each is trying to come up with an invention that will lead them to a Nobel Prize, and both are fairly eccentric. Ruzenka is in the medical field and has found a formula that she's named “KR VI” that can take undesirable qualities about dreams and replace them with pleasant ones. Jindrich is an engineer trying to find a way to increase production in his otherwise incompetent firm.