Kiss Meets the Phantom of the Park

At the height of their superstardom in 1978 it was time for the Kabuki make-up sporting rock band Kiss (Gene Simmons, Paul Stanley, Peter Criss, Ace Frehley) to branch out into the movies. After all, it was the same year that The Bee Gees starred in the super dud, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Instead of going the way The Beatles did 14 years earlier when they hooked up with an acclaimed young director, Richard Lester, to helm their little masterpiece A Hard Day’s Night, Kiss wanted an easier cash-in, or so the story goes. So instead of doing an edgy film to keep up with their violent, hard rockin’ persona, they hooked up with TV cartoon producers Hanna-Barbera (The Flintstones, Yogi Bear, etc.) in the hopes of selling their products to a much younger audience and ended up with a disastrous TV-movie that the band has more or less disowned. Though not as campy as The Ramones in Rock ‘n’ Roll High School or as weird as The Monkees in Head or as boring as Neil Diamond in The Jazz Singer, it is a few levels better than The Village People opus, Can’t Stop the Music. Kiss Meets The Phantom of the Park is truly one of the great oddities in the mixing of rock stars and celluloid; it can be hard to find on DVD as it’s only available in different bootleggy editions (and surprisingly a European cut is on a Kiss anthology DVD), but as a pure piece of cultural fascination and laugh-out-loud absurdity it’s worth seeking out.

At the height of their superstardom in 1978 it was time for the Kabuki make-up sporting rock band Kiss (Gene Simmons, Paul Stanley, Peter Criss, Ace Frehley) to branch out into the movies. After all, it was the same year that The Bee Gees starred in the super dud, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Instead of going the way The Beatles did 14 years earlier when they hooked up with an acclaimed young director, Richard Lester, to helm their little masterpiece A Hard Day’s Night, Kiss wanted an easier cash-in, or so the story goes. So instead of doing an edgy film to keep up with their violent, hard rockin’ persona, they hooked up with TV cartoon producers Hanna-Barbera (The Flintstones, Yogi Bear, etc.) in the hopes of selling their products to a much younger audience and ended up with a disastrous TV-movie that the band has more or less disowned. Though not as campy as The Ramones in Rock ‘n’ Roll High School or as weird as The Monkees in Head or as boring as Neil Diamond in The Jazz Singer, it is a few levels better than The Village People opus, Can’t Stop the Music. Kiss Meets The Phantom of the Park is truly one of the great oddities in the mixing of rock stars and celluloid; it can be hard to find on DVD as it’s only available in different bootleggy editions (and surprisingly a European cut is on a Kiss anthology DVD), but as a pure piece of cultural fascination and laugh-out-loud absurdity it’s worth seeking out.

The opening credits include Kiss performing their mega-hit “Rock and Roll All Nite,” but then they take a breather, absent from the movie’s incredibly long-feeling first act. California’s Magic Mountain amusement park employs a brilliant inventor with a high-tech lab; unfortunately, though, the hype around Kiss performing at the park has turned Abner Devereaux (Anthony Zerbe, who played the similarly creepy Matthias in The Omega Man) into some kind of mad doctor. Doctor Abe builds lifelike cyber robots that appear all over the park, but when a pesky employee, Sam (Terry Lester fresh from TV’s Ark II), takes a break from wooing his girlfriend, Melissa (Deborah Ryan), to asks Abe a few questions the mad man turns him into some kind of robotic zombie with a mind control switch attached to his neck. The doc then has fun messing with a trio of rowdy bikers: Chopper, Slime, and Dirty Dee, before his robots attack them. Also about every 10 minutes the screen dramatically fades to black for commercial breaks.

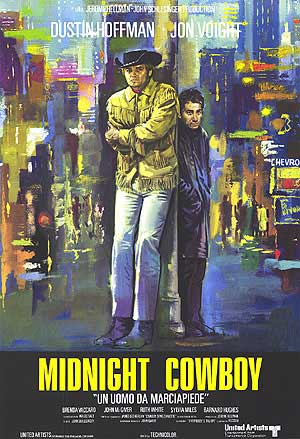

Midnight Cowboy

Though “X-rated” means something different than it did in 1969, it’s still a badge of honor that Midnight Cowboy is the only film with that “for adults only” label to have won the Best Picture Oscar (Last Tango in Paris being the other great “X-rated” flick of the era). Midnight Cowboy is less shocking today; sexually, it’s not the graphic images that provide the punch it’s the intellectually complicated nature of the characters’ sexuality that still can move an audience. As a follow up to The Graduate, Dustin Hoffman proved he was more than a one-hit wonder and instead that he had a long and vital career ahead of him. It also deservedly made a star out of a little known pretty-boy actor named Jon Voight. And it also put British director John Schlesinger on the American A-list, a guy whose deep sensitivity and open homosexuality put him ahead of his time. The film’s theme song, “Everybody’s Talkin’” performed by Harry Nilsson, has become the iconic standard bearer for images of a lonely guy walking the streets of New York. Midnight Cowboy also is a fascinating peek at an era both for representation for how an artist works at a time when the movie studios were willing to take a chance on a grubby flick about a would-be male prostitute and his new BFF while also revealing a dark side to the Big Apple during what has sometimes been considered a golden age of self-expression.

Though “X-rated” means something different than it did in 1969, it’s still a badge of honor that Midnight Cowboy is the only film with that “for adults only” label to have won the Best Picture Oscar (Last Tango in Paris being the other great “X-rated” flick of the era). Midnight Cowboy is less shocking today; sexually, it’s not the graphic images that provide the punch it’s the intellectually complicated nature of the characters’ sexuality that still can move an audience. As a follow up to The Graduate, Dustin Hoffman proved he was more than a one-hit wonder and instead that he had a long and vital career ahead of him. It also deservedly made a star out of a little known pretty-boy actor named Jon Voight. And it also put British director John Schlesinger on the American A-list, a guy whose deep sensitivity and open homosexuality put him ahead of his time. The film’s theme song, “Everybody’s Talkin’” performed by Harry Nilsson, has become the iconic standard bearer for images of a lonely guy walking the streets of New York. Midnight Cowboy also is a fascinating peek at an era both for representation for how an artist works at a time when the movie studios were willing to take a chance on a grubby flick about a would-be male prostitute and his new BFF while also revealing a dark side to the Big Apple during what has sometimes been considered a golden age of self-expression.

Apparently screenwriter Waldo Salt (who was just emerging from two decades of being blacklisted) took a lot of liberties with James Leo Herlihy’s underground but acclaimed novel. A Texas dishwasher named Joe Buck (Voight) decides to drop his apron and take advantage of his good looks; he busses up to Manhattan under the illusion that it’s a city full of rich women and fairies. They need a real cowboy to show them what a true man is. Unfortunately life in the big city doesn’t turn out like he hoped. There’s competition in the cowboy hustler department and most people are not charmed by his act. He does finally hook up with a seemingly wealthy older woman but when he requests payment for his services, she turns the tables and he ends up paying her. Similar trysts with two men, a religious nut and a teenage boy (a young Bob Balaban), prove fruitless as Joe is kicked out of his pad and finds himself cold, hungry, and homeless.

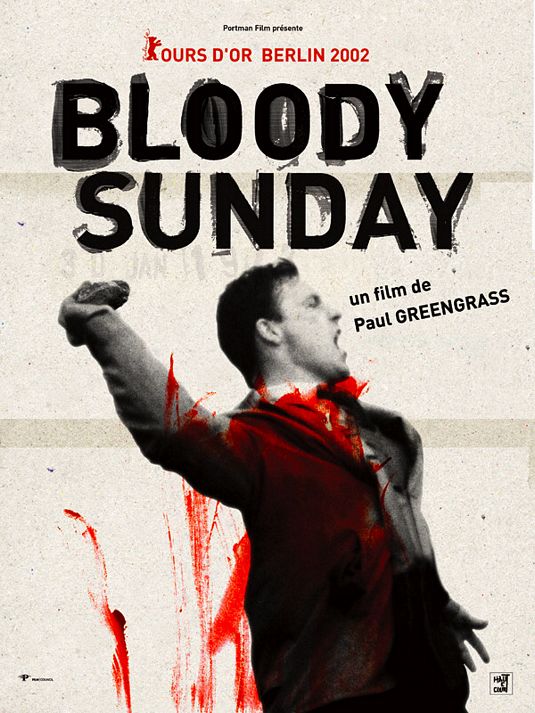

Bloody Sunday

One of the best examples of docu-realism in the Battle of Algiers-mode, Bloody Sunday, from director and writer Paul Greengrass, was originally made for Granada Television (a high quality UK outfit) but after an acclaimed screening at the Sundance Film Festival it got its theatrical run and instantly made Greeengrass a director in high demand. He went on to direct the final two Bourne flicks as well as another outstanding docu-drama, United 93. Bloody Sunday tensely recreates the events of the 1972 peace march in the Bogside of Derry, Northern Ireland that spiraled out of control as itchy trigger fingered British paratroopers opened fire on marchers killing 14 and then covering their own actions. The film tries to show the points of view of both sides, but no matter how even-handed the film intended to be, and even with the usual IRA types running around looking for a fight, it’s impossible to see it as anything less than a British massacre of the innocent.

One of the best examples of docu-realism in the Battle of Algiers-mode, Bloody Sunday, from director and writer Paul Greengrass, was originally made for Granada Television (a high quality UK outfit) but after an acclaimed screening at the Sundance Film Festival it got its theatrical run and instantly made Greeengrass a director in high demand. He went on to direct the final two Bourne flicks as well as another outstanding docu-drama, United 93. Bloody Sunday tensely recreates the events of the 1972 peace march in the Bogside of Derry, Northern Ireland that spiraled out of control as itchy trigger fingered British paratroopers opened fire on marchers killing 14 and then covering their own actions. The film tries to show the points of view of both sides, but no matter how even-handed the film intended to be, and even with the usual IRA types running around looking for a fight, it’s impossible to see it as anything less than a British massacre of the innocent.

Inspired by the American civil rights movement, the Catholics of Northern Ireland lived in a near police state under British control; the marchers even used “We Shall Overcome” as their theme song. The march was led by their local MP, Ivan Cooper, ironically a Protestant himself leading a peaceful Catholic rebellion. As played brilliantly by James Nesbitt, Cooper is the epitome of good intentions in a bad situation; he often references his idol Martin Luther King and does everything he can do to keep his marchers peaceful, but unfortunately for him this is Northern Ireland not Selma. The Northern Ireland-born Nesbitt, a staple on UK TV, was mostly known for lightweight fare like the show Cold Feet; here he gives the performance of his career. It’s a stunning piece of acting; Cooper is desperate to lead, but the weight of events is just too overpowering for him and Nesbitt earns the viewer’s respect while our hearts go out to him.

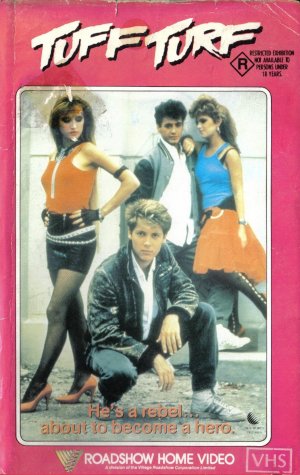

Tuff Turf

Like a stunned archaeologist I happened upon a relic from the past that may be a Holy Grail for shining light on an era and a people; it’s a little movie called Tuff Turf. Perhaps it can be used not to tell us about life in 1985 — I imagine that any relation to actual life is purely coincidental — no, it tells us more about the hack filmmakers of that period. Like so many films about young people in that period, the filmmakers are highly influenced by the worst qualities of music videos and seem intent on filling the movie with banal musical interludes. It’s a mix of Class of 1984 and Footloose (which obviously includes some Rebel without a Cause), mixing in live performances but without the skill of Streets of Fire. Yes, it’s supposed to be a gritty school gang vs. the new guy flick, but where flicks like Class of 1984 and even Bad Boys were legitimately disturbing, even with some heavy moments of violence Tuff Turf carries the influential stamp of Grease 2, or worse, ‘60s beach movies. There’s actually a shocking moment when the kids break out in a spontaneous, highly choreographed dance number (no, really); any state of edge in the film is an accident. Oh, and the editing and timing are completely stilted and awkward. However, these minor grievances aside, Tuff Turf is a bad film; as a matter of fact its severe mediocrity actually makes it all the more fascinating and entertaining.

Like a stunned archaeologist I happened upon a relic from the past that may be a Holy Grail for shining light on an era and a people; it’s a little movie called Tuff Turf. Perhaps it can be used not to tell us about life in 1985 — I imagine that any relation to actual life is purely coincidental — no, it tells us more about the hack filmmakers of that period. Like so many films about young people in that period, the filmmakers are highly influenced by the worst qualities of music videos and seem intent on filling the movie with banal musical interludes. It’s a mix of Class of 1984 and Footloose (which obviously includes some Rebel without a Cause), mixing in live performances but without the skill of Streets of Fire. Yes, it’s supposed to be a gritty school gang vs. the new guy flick, but where flicks like Class of 1984 and even Bad Boys were legitimately disturbing, even with some heavy moments of violence Tuff Turf carries the influential stamp of Grease 2, or worse, ‘60s beach movies. There’s actually a shocking moment when the kids break out in a spontaneous, highly choreographed dance number (no, really); any state of edge in the film is an accident. Oh, and the editing and timing are completely stilted and awkward. However, these minor grievances aside, Tuff Turf is a bad film; as a matter of fact its severe mediocrity actually makes it all the more fascinating and entertaining.

Understanding what motivates the lead character Morgan Hiller is a challenge for viewers because he’s played by a young James Spader, who even in his best performance (Sex, Lies, and Videotape) can come off as aloof and odd, as if he’s Christopher Walken’s prettier younger brother. After a long music video credit sequence, the film opens with a group of Los Angeles Valley teen toughs straight out of Michael Jackson’s “Beat It” video, mugging a civilian. The hair-sprayed bandanna gang is led by big-chested Nick (thirty-something looking Paul Mones) and his devoted main squeeze, Frankie (child star later turned reality TV mess, Kim Richards). Morgan rides his bike, whistling past the gang spray painting their faces and ruining their crime. Is he some kind of teen vigilante? Nope, just an East Coast rich kid who relocated to L.A. after his family fortune went bust. Now this former prep school rebel has to figure out how to fit in at a rough public school; it didn’t help to make enemies with Nick and his crew. Even after they publicly mess up his bicycle the nearly fearless Morgan continues to woo the much more “street” Frankie, pushing Nick’s wrath even further.

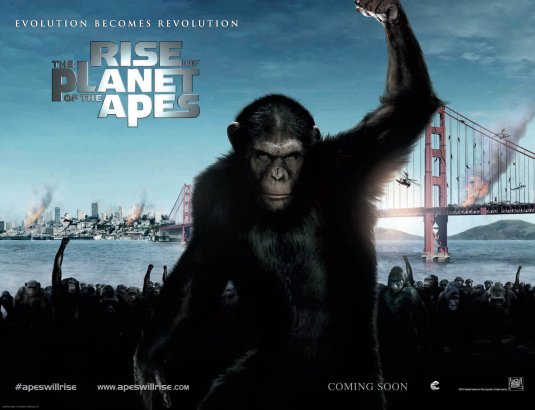

Rise of the Planet of the Apes

When the legacy of a film that you a feel deep affection for is messed with the knee-jerk reaction can be negative; every once in a while a remake can be respected (Dawn of the Dead) or a sequel can outdo the original (The Road Warrior, Aliens) but most sequels and remakes are strictly quick buck affairs. So there’s no point in getting snotty about Rise of the Planet of the Apes; it’s a big, fun, flawed but intelligent reimagining of the series. It’s the best Apes flick since the original film, Planet of the Apes in 1968, one of my all-time favorite movies. The legacy has already been contaminated; the quality of the four sequels (Beneath…, Escape from…, Conquest of…, and Battle for…) vary in quality. Both the live action and animated television series, based on the film, are amazingly boring. And Tim Burton’s ill-conceived remake was a dud. Frankly, fans of Pierre Boulle’s original book have the most to complain about as the ‘68 version’s screenwriters, Rod Serling and Michael Wilson, hit the bull’s-eye, but completely abandoned much of the novel’s concept. The rebooting of a stale series has done wonders in recent years for both Batman and James Bond; rebooting as opposed to remaking looks to be the new way to find new creative angles.

When the legacy of a film that you a feel deep affection for is messed with the knee-jerk reaction can be negative; every once in a while a remake can be respected (Dawn of the Dead) or a sequel can outdo the original (The Road Warrior, Aliens) but most sequels and remakes are strictly quick buck affairs. So there’s no point in getting snotty about Rise of the Planet of the Apes; it’s a big, fun, flawed but intelligent reimagining of the series. It’s the best Apes flick since the original film, Planet of the Apes in 1968, one of my all-time favorite movies. The legacy has already been contaminated; the quality of the four sequels (Beneath…, Escape from…, Conquest of…, and Battle for…) vary in quality. Both the live action and animated television series, based on the film, are amazingly boring. And Tim Burton’s ill-conceived remake was a dud. Frankly, fans of Pierre Boulle’s original book have the most to complain about as the ‘68 version’s screenwriters, Rod Serling and Michael Wilson, hit the bull’s-eye, but completely abandoned much of the novel’s concept. The rebooting of a stale series has done wonders in recent years for both Batman and James Bond; rebooting as opposed to remaking looks to be the new way to find new creative angles.

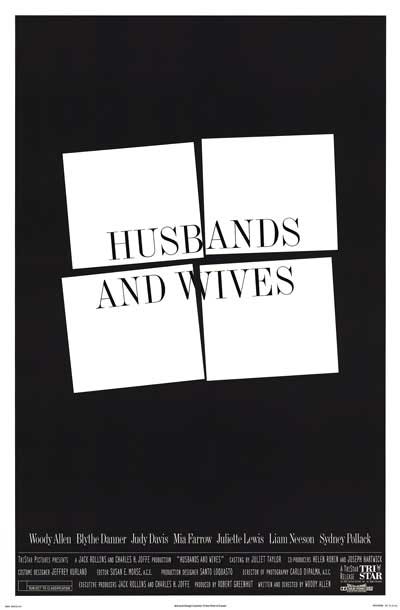

Husbands and Wives

If Annie Hall was Woody Allen’s ode to falling in love, 15 years later Husbands and Wives is an examination of falling out of love. Where the look and style of Annie Hall was clean and precise, Husbands and Wives is franticly shot handheld with herky-jerky editing and an almost improvised vibe to the performances. If Annie Hall marked the beginning of Allen’s great run of introspective masterpieces and near masterpieces, Husbands and Wives is the end of the streak. It’s his last really important Woody Allen film and definitely his last strong acting performance before he fell into a cliché of himself or brought in other actors to substitute, aping his own famous mannerisms. Husbands and Wives doesn’t have as many laughs as some of his earlier work but the insights into relationships can be utterly nerve striking. Made during his dramatic break up with his then wife Mia Farrow, it may be the last time Allen really had something he wanted to say or was worth hearing.

If Annie Hall was Woody Allen’s ode to falling in love, 15 years later Husbands and Wives is an examination of falling out of love. Where the look and style of Annie Hall was clean and precise, Husbands and Wives is franticly shot handheld with herky-jerky editing and an almost improvised vibe to the performances. If Annie Hall marked the beginning of Allen’s great run of introspective masterpieces and near masterpieces, Husbands and Wives is the end of the streak. It’s his last really important Woody Allen film and definitely his last strong acting performance before he fell into a cliché of himself or brought in other actors to substitute, aping his own famous mannerisms. Husbands and Wives doesn’t have as many laughs as some of his earlier work but the insights into relationships can be utterly nerve striking. Made during his dramatic break up with his then wife Mia Farrow, it may be the last time Allen really had something he wanted to say or was worth hearing.

Besides the French New Wave camera work and cutting, there’s an occasional narrator and interviews with the characters; what was meant to give the film a documentary feel actually seems now to predate reality TV. Gabe (Allen), a writer and college professor, is in a stale marriage to Judy (Farrow); they are shocked when, before a dinner date, their good friends Jack (Sidney Pollack) and Sally (Judy Davis) announce their separation. Subconsciously it may expose their inner doubts about their own marriage. Jack quickly gets a much younger girlfriend, an aerobics trainer named Sam (Lysette Anthony), while Sally’s dating life is less successful until Judy introduces her to her coworker, the sweetly hunky Michael (Liam Neeson). Meanwhile Gabe and Judy argue about having a child and his indifference towards her writing aspirations. Gabe befriends a young writing student, Rain (Julliette Lewis replacing Emily Lloyd who was fired after shooting begun), with whom he finds a creative (and potentially sexual) bond that he doesn’t have with Judy. From there the couple’s relationships get worse, better, and worse.

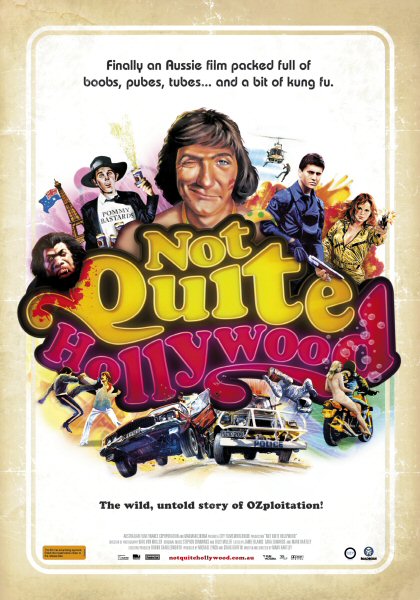

Not Quite Hollywood: The Wild, Untold Story of Ozploitation!

While Peter Weir and Fred Schepisi were putting Australian cinema on the map in the 1970s with films like Picnic at Hanging Rock and The Devil’s Playground, an amazing underworld of exploitation cinema was also happening Down Under full of sex and violence, exuberantly captured by director Mark Hartley in his slam bang documentary Not Quite Hollywood: The Wild, Untold Story of Ozploitation! Like his more recent ode to Filipino exploitation flicks, Machete Maidens Unleashed, Hartley has found the perfect formula for honoring the less honorable world cinema. Tracing Australia’s growth from sexploitation through stuntploitation and finally peaking with George Miller’s masterful Mad Max and Mad Max 2: The Road Warrior (known in the U.S. as The Road Warrior). With a plethora of wall-to-wall clips and both informative and entertaining talking heads telling the story including Quentin Tarantino, George Lazenby, Brian Trenchard-Smith, John Waters, and Richard Franklin, this movie is an absolute blast.

While Peter Weir and Fred Schepisi were putting Australian cinema on the map in the 1970s with films like Picnic at Hanging Rock and The Devil’s Playground, an amazing underworld of exploitation cinema was also happening Down Under full of sex and violence, exuberantly captured by director Mark Hartley in his slam bang documentary Not Quite Hollywood: The Wild, Untold Story of Ozploitation! Like his more recent ode to Filipino exploitation flicks, Machete Maidens Unleashed, Hartley has found the perfect formula for honoring the less honorable world cinema. Tracing Australia’s growth from sexploitation through stuntploitation and finally peaking with George Miller’s masterful Mad Max and Mad Max 2: The Road Warrior (known in the U.S. as The Road Warrior). With a plethora of wall-to-wall clips and both informative and entertaining talking heads telling the story including Quentin Tarantino, George Lazenby, Brian Trenchard-Smith, John Waters, and Richard Franklin, this movie is an absolute blast.

While films were filmed in and about Australia, they were usually films like Wake in Fright and Walkabout that were made by foreigners; originally Australia’s most popular film exports were soft porny sex comedies with such titles as The Naked Bunyip, Alvin Rides Again, and Again! And Again! And Again! and The Sex Therapist. While Australians were enjoying idiotic homemade comedies with the “Ocker” films (which crudely made fun of Australian hick values) like Alvin Purple, Stork, and The Adventures of Barry McKenzie (directed by Bruce Beresford who would eventually go more high brow with his Australian masterpiece Braker Morant).

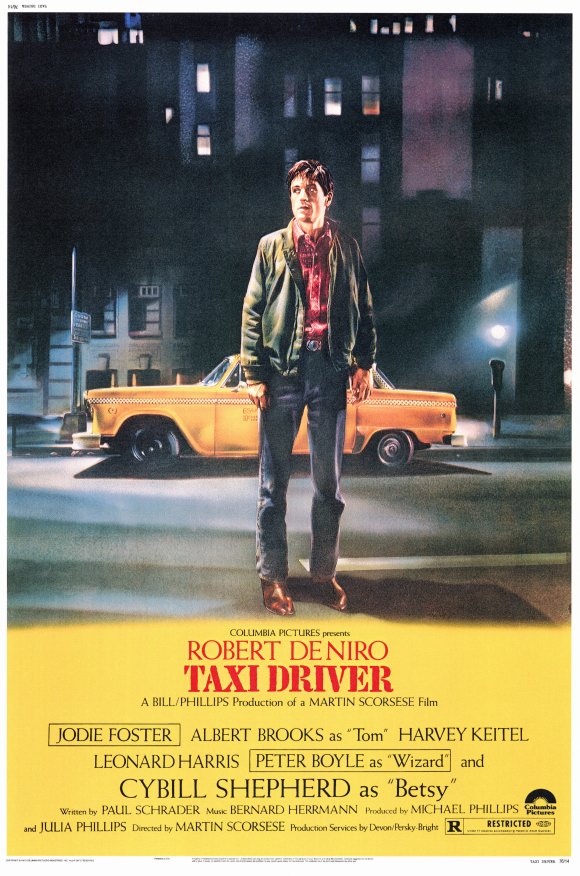

Taxi Driver

The culty acclaim of Martin Scorsese’s 1976 Taxi Driver is mostly deserved; the film is made up of some of the greatest scenes and moments of the decade. But with that there are some scenes and moments that don’t work as well. Really what Taxi Driver is is a good ol’ fashioned 70s exploitation flick, gussied up with a big-time director and cast. It’s a perfect combination of two of the era’s most potent B-movie formulas, “the crazy Vietnam vet” flick and “the New York city loner vigilante” saga. Two genres of exploitation pulp that go together like peanut butter and chocolate, after a while you can’t imagine one without the other. Like Scarlet O’Hara or Forest Gump, the name Travis Bickle has become a cultural definition of a type. Robert De Niro, at the peak of his thespian prowess, plays the lonely city taxi driver who prowls the street in search of some kind of meaning for his life. Teaming with Scorsese for the second time (after the brilliant Mean Streets, and with six more collaborations to come), it’s one of the great actor’s most iconic roles, and still a signature film for the director.

The culty acclaim of Martin Scorsese’s 1976 Taxi Driver is mostly deserved; the film is made up of some of the greatest scenes and moments of the decade. But with that there are some scenes and moments that don’t work as well. Really what Taxi Driver is is a good ol’ fashioned 70s exploitation flick, gussied up with a big-time director and cast. It’s a perfect combination of two of the era’s most potent B-movie formulas, “the crazy Vietnam vet” flick and “the New York city loner vigilante” saga. Two genres of exploitation pulp that go together like peanut butter and chocolate, after a while you can’t imagine one without the other. Like Scarlet O’Hara or Forest Gump, the name Travis Bickle has become a cultural definition of a type. Robert De Niro, at the peak of his thespian prowess, plays the lonely city taxi driver who prowls the street in search of some kind of meaning for his life. Teaming with Scorsese for the second time (after the brilliant Mean Streets, and with six more collaborations to come), it’s one of the great actor’s most iconic roles, and still a signature film for the director.

As a guy who doesn’t need sleep and doesn’t mind venturing in to the rougher sides of town, Travis is instantly hired as a cabbie. He learned some of the ropes from colleagues over late night coffee stops, led by Wizard (go-to working class character actor Peter Boyle). His clientele ranges from the high end to creeps (Scorsese in a fantastic scene), and pimps and hookers—that’s where he meets and becomes kinda obsessed with Iris (Jodie Foster), a teenage hooker who was briefly fleeing her pimp, Sport (Harvey Keitel). He also strikes up a near romance with a beautiful campaign worker, Betsy (Cybill Sheperd), who works for senator Palantine (Leonard Harris). Though her coworker (Albert Brooks) has his doubts about Travis, she agrees to go out with him. He blows it when he idiotically takes her to see a porn movie. Getting blown off by her gives him more time to fret over Iris; his obsession with her does not seem to be sexual, he just has a high moral code and feels like he can help her. And he sinks deeper into a type of self-obsessed heroic fantasy. After killing a guy who attempts to rob a grocery store his itch for more action grows so he gives himself a Mohawk hairdo and makes a feeble attempt at shooting Palantine. Instead, when that doesn’t work out he goes after Iris’s pimp, culminating in an extremely bloody shoot-out with him and the whorehouse manager in front of Iris, where he kills both of them and gets shot up himself.

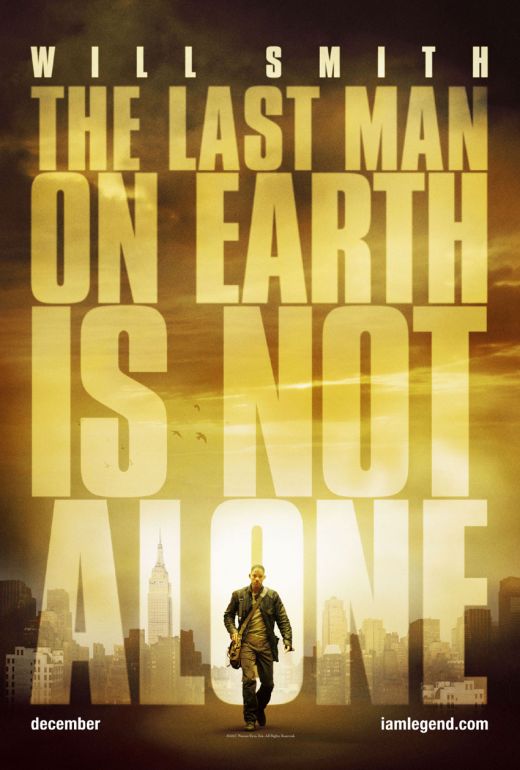

I Am Legend

Is it possible to love a movie and recommend it but still advise to turn it off just after the half-way mark? The history of films with great Act Ones and maybe even Act Twos that then fall apart by Act Three constitutes a long list (Mulholland Dr., From Dusk Till Dawn, Full Metal Jacket, etc.). I Am Legend may be the most extreme case. It has a pretty spectacular first half that’s suspenseful, exciting, but by that last act things go terribly astray. Based on the classic novelette by the great writer Richard Matheson, it had been filmed twice earlier— first in the ‘60s as a dull low-budget Vincent Price flick called The Last Man on Earth and then the culty Charlton Heston early ‘70s vehicle re-titled The Omega Man. I don’t remember ever making it all the way through the Price version, but the beloved Heston flick had the same problem as the newest take; though the whole of the ‘70s film is so goofy that the plot twist in the second half is less abrupt and problematic than in the newer more “realistic” version, they both have great set-ups that couldn’t carry through to the end.

Is it possible to love a movie and recommend it but still advise to turn it off just after the half-way mark? The history of films with great Act Ones and maybe even Act Twos that then fall apart by Act Three constitutes a long list (Mulholland Dr., From Dusk Till Dawn, Full Metal Jacket, etc.). I Am Legend may be the most extreme case. It has a pretty spectacular first half that’s suspenseful, exciting, but by that last act things go terribly astray. Based on the classic novelette by the great writer Richard Matheson, it had been filmed twice earlier— first in the ‘60s as a dull low-budget Vincent Price flick called The Last Man on Earth and then the culty Charlton Heston early ‘70s vehicle re-titled The Omega Man. I don’t remember ever making it all the way through the Price version, but the beloved Heston flick had the same problem as the newest take; though the whole of the ‘70s film is so goofy that the plot twist in the second half is less abrupt and problematic than in the newer more “realistic” version, they both have great set-ups that couldn’t carry through to the end.

The new version opens with a TV broadcasting a news show; Doctor Krippin (an uncredited Emma Thompson) declares they have engineered a virus that will cure cancer. Cut: it’s three years later and an abandoned Manhattan looks straight out of the History Channel’s Life After People; nature has taken it back with plant growth covering Times Square and wild animals now living freely on the island (using both CGI and actual redressed New York locations). Robert Neville (Will Smith) seems to be the last man alive; he speeds around Manhattan with his dog Sam (or Samantha), hunting elk, losing out on his latest prey to a pack of lions. Neville was a military scientist and had worked with the team that invented the miracle drug that eventually wiped out civilization. Though he is immune, he looks for a cure by testing lab rats in the basement lab of his Washington Square brownstone, when he’s not hitting golf balls off a aircraft carrier and broadcasting his daily radio plea for any survivors to come find him.

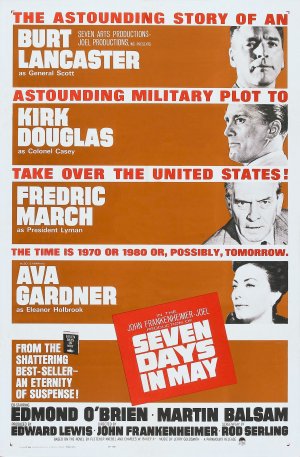

Seven Days in May

With the Cold War in full swing, the saga of President Kennedy peaking, another potential war in Asia, and nuclear proliferation moving at a rapid pace, the early ‘60s inspired a slew of solid political flicks. From nuclear madness came Fail-Safe, Dr. Strangelove, and On the Beach. Political soap operas inspired Advise & Consent and The Best Man and from those, the deep paranoia of the right, and the “military industrial complex” came director John Frankenheimer’s twisted, sorta sci-fi nightmare, The Manchurian Candidate. For Frankenheimer’s follow-up he would combine all the genres (nukes, politics and right wing paranoia) for the slick White House thriller Seven Days in May which features Burt Lancaster and Kirk Douglas appearing together for the second time, after Gunfight At The O.K. Corral (not including Lancaster’s cameo in The List of Adrian Messenger). Just as he did brilliantly in Sweet Smell of Success this time Lancaster took the supporting bad guy role. It’s a great showdown between two of Hollywood’s most sculpted physiques of their era.

With the Cold War in full swing, the saga of President Kennedy peaking, another potential war in Asia, and nuclear proliferation moving at a rapid pace, the early ‘60s inspired a slew of solid political flicks. From nuclear madness came Fail-Safe, Dr. Strangelove, and On the Beach. Political soap operas inspired Advise & Consent and The Best Man and from those, the deep paranoia of the right, and the “military industrial complex” came director John Frankenheimer’s twisted, sorta sci-fi nightmare, The Manchurian Candidate. For Frankenheimer’s follow-up he would combine all the genres (nukes, politics and right wing paranoia) for the slick White House thriller Seven Days in May which features Burt Lancaster and Kirk Douglas appearing together for the second time, after Gunfight At The O.K. Corral (not including Lancaster’s cameo in The List of Adrian Messenger). Just as he did brilliantly in Sweet Smell of Success this time Lancaster took the supporting bad guy role. It’s a great showdown between two of Hollywood’s most sculpted physiques of their era.

Based on a novel by Fletcher Knebel and Charles W. Bailey, Douglas plays Colonel Martin "Jiggs" Casey, a Pentagon Joint Chiefs of Staff aide to the powerful James Mattoon Scott (Lancaster). Jiggs is a moderate, more devoted to upholding the Constitution than playing politics, but the guys above him are stone-cold hawks and don’t like it when liberal President Jordan Lyman (Fredric March) signs a nuclear disarmament agreement with the Soviets. Reading cables, hearing secondhand conversations, and finding an incriminating crumpled note leads Jiggs to deduce that Scott is planning a military coup against The White House. He takes his suspicion directly to the president and then begins a cat and mouse game of cloak n’ dagger, teaming with the most trusted members of the president's inner circle, including his top aide, Paul Girard (Martin Balsam), a crusty drunken Southern congressman played wonderfully by Edmond O’Brien (he won an Oscar ten years earlier for his performance in The Barefoot Contessa), and finally Jiggs cozies up to a boozy Washington socialite, Eleanor Holbrook (Ava Gardner), who knows all the town’s players and harbors secrets.