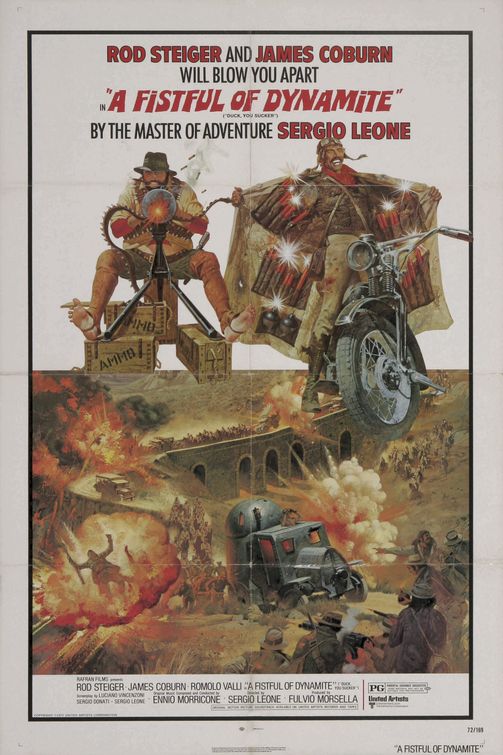

Duck, You Sucker (AKA A Fistful of Dynamite)

If Once Upon a Time in the West was Sergio Leone’s North by Northwest or Rear Window, then Duck, You Sucker (AKA A Fistful of Dynamite) was his Vertigo. It was a misunderstood film in its day; fans were startled by the director breaking from his formula and actually trying to say something. But like Hitchcock, what he had to say also didn’t satisfy what audiences wanted to hear, and the pace didn’t give them the thrills they were used to. With Duck, You Sucker, Leone was working on a potentially bigger canvas than Once Upon a Time in the West. Working with his biggest budget yet meant that Leone did have to concede his casting choices to the studio. Rod Steiger and James Coburn were hardly Leone’s first choices to play the leads, but United Artists considered both big stars while Jason Robards wasn’t bankable enough and Clint Eastwood was no longer available.

If Once Upon a Time in the West was Sergio Leone’s North by Northwest or Rear Window, then Duck, You Sucker (AKA A Fistful of Dynamite) was his Vertigo. It was a misunderstood film in its day; fans were startled by the director breaking from his formula and actually trying to say something. But like Hitchcock, what he had to say also didn’t satisfy what audiences wanted to hear, and the pace didn’t give them the thrills they were used to. With Duck, You Sucker, Leone was working on a potentially bigger canvas than Once Upon a Time in the West. Working with his biggest budget yet meant that Leone did have to concede his casting choices to the studio. Rod Steiger and James Coburn were hardly Leone’s first choices to play the leads, but United Artists considered both big stars while Jason Robards wasn’t bankable enough and Clint Eastwood was no longer available.

Throughout Leone’s Eastwood “Man with No Name” trilogy, each film was made back-to-back-to-back (A Fistful of Dollars, For a Few Dollars More and The Good, the Bad & the Ugly) and each got more progressively ambitious in both scope and ambition as their popularity grew. Finally, the director peaked with his follow-up, Once Upon a Time in the West, an accumulation of all the ideas he had been building towards and both the ultimate post-modern western and one of the true film masterpieces of the 1960s. He finally took a break (three years) before returning to the screen with the eccentric Duck, You Sucker (afterwards he would take an even longer break, not being a credited director for 11 years). In some territories the film was titled Once Upon a time in the Revolution or A Fistful of Dynamite but it would not fully fit with his first four flicks (we all tend to ignore his unrecognizable debut The Colossus Of Rhodes in ’61). Everything about this new film felt slightly tweaked. Its tones moved from comic to dramatic to sentimental to tragic to cartoony much less gracefully than in his past work. The setting moved south to Mexico and the period moved up a couple decades. Where Once Upon a Time in the West had a deliberate pace, the strands perfectly came together and justified their speed, while at almost 160 minutes Duck, You Sucker sometimes just feels long and, worse, indulgent. But luckily that indulgence and the hint of a director slightly lost in his creation proves to be both fascinating and entertaining. And just as westerns had been reinvented in the ‘60s, the ‘70s saw another seismic shift where movies as diverse as Duck, You Sucker, El Topo, The Missouri Breaks, and, finally, Heaven’s Gate would help to kill the genre for a generation.

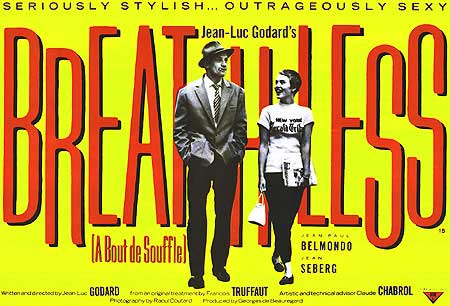

Breathless

It’s not an overstatement to say that Jean-Luc Godard’s noiry, crime-romance Breathless (À bout de souffle) may be one of the most important films of a very important film era—a game changer. For the film critic turned filmmaker, Breathless Godard’s first feature and it helped to define an exciting new cinema movement that was brewing among young cinephiles in France now known as The French New Wave. With its hand-held photography, jump cutting, improvised script, and natural lighting, it carefully broke many rules of formal cinema. Inspired by American crime films, mostly the B-movies that that generation of the French critics came to appreciate long before their American counterparts, it romanticized the underworld, without the moral lessons of so many similar American movies. The film also gives a shout-out to Jean-Pierre Melville’s Bob Le Flambeur, another film inspired by American Noirs. Playing the film’s lead, a small-time crook with a death wish, Breathless put actor Jean-Paul Belmondo on the map. His gripping and charismatic performance reeks of his influences, most notably Humphrey Bogart and Marlon Brando. Like so many filmmakers to come, from Martin Scorsese to Quentin Tarantino (who both cite Breathless as a major influence), Godard’s work, and Breathless in particular, was a tribute to the movies that came before that the director admired.

It’s not an overstatement to say that Jean-Luc Godard’s noiry, crime-romance Breathless (À bout de souffle) may be one of the most important films of a very important film era—a game changer. For the film critic turned filmmaker, Breathless Godard’s first feature and it helped to define an exciting new cinema movement that was brewing among young cinephiles in France now known as The French New Wave. With its hand-held photography, jump cutting, improvised script, and natural lighting, it carefully broke many rules of formal cinema. Inspired by American crime films, mostly the B-movies that that generation of the French critics came to appreciate long before their American counterparts, it romanticized the underworld, without the moral lessons of so many similar American movies. The film also gives a shout-out to Jean-Pierre Melville’s Bob Le Flambeur, another film inspired by American Noirs. Playing the film’s lead, a small-time crook with a death wish, Breathless put actor Jean-Paul Belmondo on the map. His gripping and charismatic performance reeks of his influences, most notably Humphrey Bogart and Marlon Brando. Like so many filmmakers to come, from Martin Scorsese to Quentin Tarantino (who both cite Breathless as a major influence), Godard’s work, and Breathless in particular, was a tribute to the movies that came before that the director admired.

After Michael (Belmondo) steals a car and then shoots a cop, he finds himself on the run. Still always playing it cool, he hides out in Paris with an American girl, Patricia (Jean Seberg), a New York Herald Tribune street vendor. Like the best of French couples they smoke a lot of cigarettes, have sex, and talk philosophically about themselves. She is in love with him, but he is selfish and utterly self-obsessed, as he makes Bogart-like faces in a mirror always trying to perfect his gangster persona. She knows he’s bad news but maybe that’s what makes her even more devoted. She may be a naive waif, but she’s also college bound; she’s not a simpleton like Sissy Spacek in Badlands, she just wants a classic bad-boy lover. Her love and her own need to survive eventually lead her to rat him out to the cops. In a long famous death scene he is shot and killed before falling breathless.

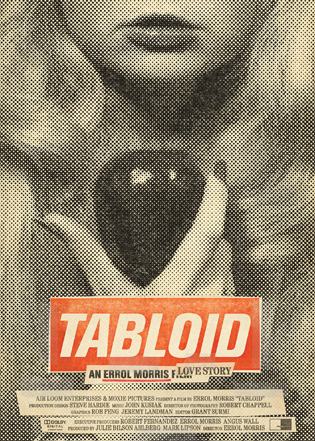

Tabloid

For over thirty years director Errol Morris has been redefining the visionary guidelines of what a documentary is and can be. He brought a deeper understanding of visual and sound construction techniques that pushed the documentary into a more compelling medium than the films that preceded his work. In the ‘80s, his film The Thin Blue Line helped get a guy off death row, but maybe more importantly, it brought the documentary genre into the mainstream and helped expose a lot of audience members and future filmmakers to the new possibilities that documentaries can achieve both socially and technically. Where many of the acclaimed filmmakers of his generation have lost their golden touch, every few years he keeps turning out a new film and he may of peaked with his last one, Tabloid, an insanely epic story of love and loss and the seedy nature of our voyeuristic society.

For over thirty years director Errol Morris has been redefining the visionary guidelines of what a documentary is and can be. He brought a deeper understanding of visual and sound construction techniques that pushed the documentary into a more compelling medium than the films that preceded his work. In the ‘80s, his film The Thin Blue Line helped get a guy off death row, but maybe more importantly, it brought the documentary genre into the mainstream and helped expose a lot of audience members and future filmmakers to the new possibilities that documentaries can achieve both socially and technically. Where many of the acclaimed filmmakers of his generation have lost their golden touch, every few years he keeps turning out a new film and he may of peaked with his last one, Tabloid, an insanely epic story of love and loss and the seedy nature of our voyeuristic society.

Morris, at his best, finds grand stories of people who live on the fringe of our culture with twisted obsessions, whether pet cemeteries (Gates of Heaven), holocaust denying (Mr. Death: The Rise and Fall of Fred A. Leuchter, Jr.) or mole rats and trapezes (Fast, Cheap & Out of Control). Morris has a canny ability to park his camera inside the brains of these kooks and come to understand or appreciate their causes. His best films have been his eccentric bios, also usually about a sort of obsession that eats at his subjects like Stephen Hawking (A Brief History of Time) and Robert S. McNamara (The Fog of War). Tabloid is almost an accumulation of his life’s work, combining all of what he does best and turning the dial up. It’s a bio of a former beauty queen named Joyce McKinney who sits on camera and tells her crazy and kinky story, aided by other talking heads and archive footage and a lot of press clippings. Without moralizing or taking sides, this is Morris’s most creatively laid-out spectacle, yet the quirkiness and perversion never outweigh the filmmaking.

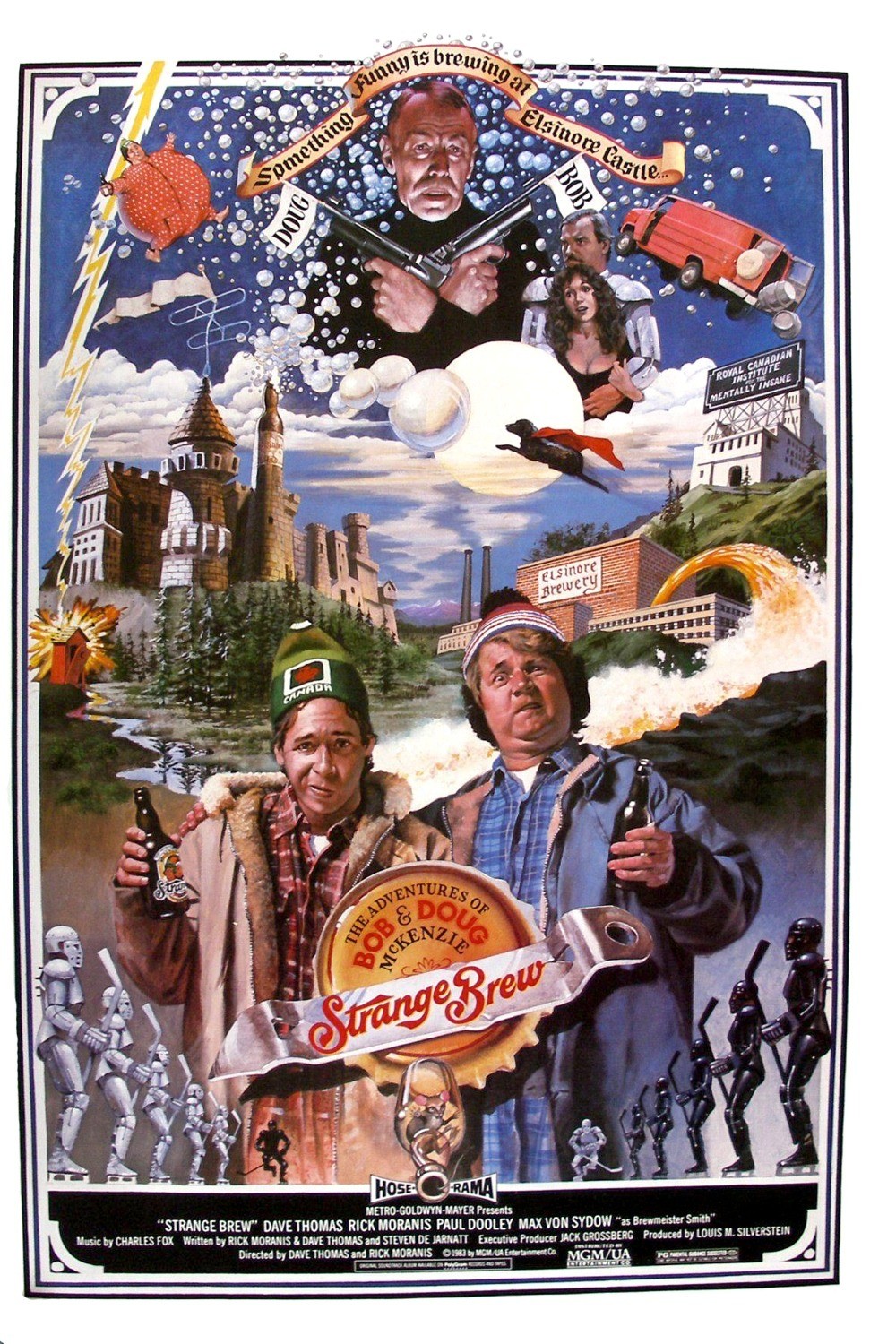

The Adventures of Bob & Doug McKenzie: Strange Brew

Movies that originate as television sketches and skits usually lead to lame products: A Night at the Roxbury, The Ladies Man, Stuart Saves His Family (has anyone ever heard of or seen the Laugh-In spin-off The Maltese Bippy?), to name but a few of the forgettable titles. There have been a few good exceptions: The Blues Brothers and Wayne’s World, and even The Coneheads has its admirers. The most unusual adaptation of a skit and a very special movie in its own right is the Canadian flick The Adventures of Bob & Doug McKenzie: Strange Brew, which emanated from Saturday Night Live’s northern and usually better little cousin SCTV. The characters, Bob (Rick Moranis) and Doug McKenzie (Dave Thomas), became SCTV’s first breakout stars and even a minor cultural phenomenon with their catchphrase “take off, you hoser.” Like Wayne’s World years later, they were a couple hicks—brothers who hosted a public access cable show called “Great White North” and the jokes usually centered on Canadian stereotypes and their love of beer and hockey. Though their minor-hit song “Take Off” (with Geddy Lee of Rush) might have caused a bigger ripple then their movie did, over the years Strange Brew has found more fans and can now be appreciated for what it is, an incredibly goofy but lovable laugh-out-loud comedy.

Movies that originate as television sketches and skits usually lead to lame products: A Night at the Roxbury, The Ladies Man, Stuart Saves His Family (has anyone ever heard of or seen the Laugh-In spin-off The Maltese Bippy?), to name but a few of the forgettable titles. There have been a few good exceptions: The Blues Brothers and Wayne’s World, and even The Coneheads has its admirers. The most unusual adaptation of a skit and a very special movie in its own right is the Canadian flick The Adventures of Bob & Doug McKenzie: Strange Brew, which emanated from Saturday Night Live’s northern and usually better little cousin SCTV. The characters, Bob (Rick Moranis) and Doug McKenzie (Dave Thomas), became SCTV’s first breakout stars and even a minor cultural phenomenon with their catchphrase “take off, you hoser.” Like Wayne’s World years later, they were a couple hicks—brothers who hosted a public access cable show called “Great White North” and the jokes usually centered on Canadian stereotypes and their love of beer and hockey. Though their minor-hit song “Take Off” (with Geddy Lee of Rush) might have caused a bigger ripple then their movie did, over the years Strange Brew has found more fans and can now be appreciated for what it is, an incredibly goofy but lovable laugh-out-loud comedy.

Adding elements of science-fiction and thriller, while referencing everything from Omega Man to Hamlet to Star Wars to the early Canadian gross-out flicks of David Cronenberg, Strange Brew opens with a movie within a movie within a movie. Surrounded by cases of Canadian beer, Bob and Doug host their TV show “Great White North” on the big screen. They run a projector of their homemade “Max Maxy” post-apocalypse flick, which leads to pandemonium in the actual theater where now Bob and Doug sit watching. They refund a distraught father his admission money (his crying kids saved all year to go see the movie), and this gets the real plot rolling—that it was their father’s beer money (the father’s voice is supplied with an amazing voice-cameo by animation legend Mel Blanc).

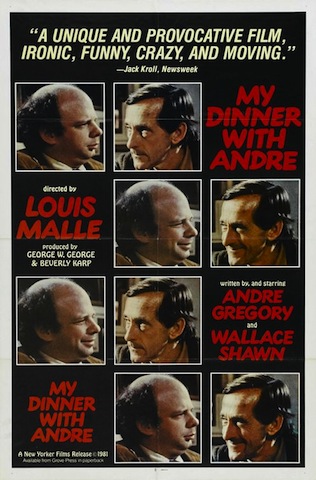

My Dinner with Andre

French director Louis Malle’s incredibly diverse career ranged from the exciting rule-bending era of the French New Wave to his documentary period, his work during the cinema revolution of the ‘70s, and finally to his American phase. Perhaps no film was more ground breaking then his astonishingly simple, yet hugely entertaining My Dinner with Andre—what is essentially a couple hours of two men who hadn’t seen each other in some time having a fascinating discussion over dinner.

French director Louis Malle’s incredibly diverse career ranged from the exciting rule-bending era of the French New Wave to his documentary period, his work during the cinema revolution of the ‘70s, and finally to his American phase. Perhaps no film was more ground breaking then his astonishingly simple, yet hugely entertaining My Dinner with Andre—what is essentially a couple hours of two men who hadn’t seen each other in some time having a fascinating discussion over dinner.

Andre Gregory and Wallace Shawn, both known from the New York cultural and theater scene, play “Andre Gregory” and “Wallace Shawn,” which is to say they play themselves or at least variations on themselves. In real life Gregory had made a name for himself as an experimental theater director, traveling the world in search of groovy artistic expression. (He was a sometimes actor post-My Dinner with Andre, most memorably as John the Baptist in The Last Temptation of Christ). Shawn, the son of legendary long-time New Yorker editor William Shawn (which gave him lifelong NY high-brow street-cred) had some success as an off-off Broadway playwright, but ever since Woody Allen cast him as Diane Keaton’s ex-husband in Manhattan he has worked steadily as a character actor. The two started to record their own conversations and then got director Malle involved to help shape it into a script.

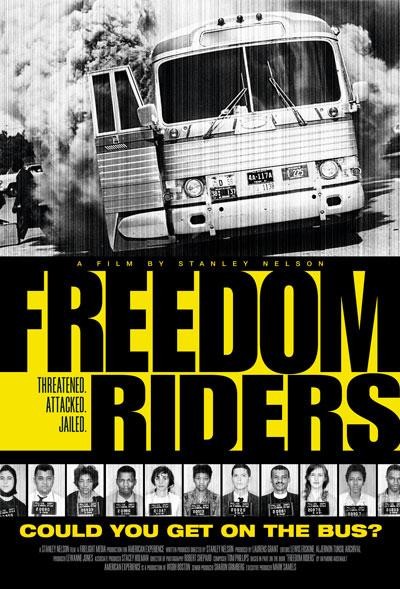

Freedom Riders

After the success of student lunch counter sit-ins, anti-segregation forces, led by a little know group called CORE (Committee of Racial Equality), decided to push the envelope in an attempt to secure their rights and bring attention to the discrimination of black Americans in the psychotically racist American South. PBS’s American Experience does it again! Freedom Riders is another historical masterpiece; with spectacular archive footage and engaging talking heads, director Stanley Nelson perfectly lays out this dangerous and complicated story. Along with the epic Eyes on the Prize, Freedom Riders is essential viewing for anyone interested in the civil rights movement or just a fascinating and entertaining slice of brutal American history.

After the success of student lunch counter sit-ins, anti-segregation forces, led by a little know group called CORE (Committee of Racial Equality), decided to push the envelope in an attempt to secure their rights and bring attention to the discrimination of black Americans in the psychotically racist American South. PBS’s American Experience does it again! Freedom Riders is another historical masterpiece; with spectacular archive footage and engaging talking heads, director Stanley Nelson perfectly lays out this dangerous and complicated story. Along with the epic Eyes on the Prize, Freedom Riders is essential viewing for anyone interested in the civil rights movement or just a fascinating and entertaining slice of brutal American history.

In a post-World War II America, blacks were experiencing new gains both economically and socially in much of the country. By the mid-50s the Supreme Court decision on Brown v. Board of Education brought a new promise for equal rights in schools, but the South was doing everything it could to stifle integration in education leading to a number of famous conflicts. In Montgomery a young pastor named Martin Luther King became an international superstar of peace leading their city’s bus boycotts. By 1960 black Southern college students took up the call first in Greensboro and then Nashville, doing lunch counter sit-ins to desegregate the powerful downtown department store restaurants. This all led to a discussion by a bi-racial Northern group called CORE to test the limits of a federal order to desegregate interstate bus travel including Southern bus station waiting rooms, cafeterias, and bathrooms that still had signs declaring “white” and “colored.” The South was not going to let the Federal Government tell them to change their culture and Kennedy’s White House had no interest in getting involved and alienating Southern white Democrats.

The Wild One

Though that amazing string of performances in A Streetcar Named Desire, Viva Zapata!, Julius Caesar, and On the Waterfront earned Marlon Brando four straight Oscar nominations (finally winning for Waterfront) and made him the most celebrated acting talent of his generation, it’s actually his work as Johnny in The Wild One that made him an icon of rebellion and helped inspire the youth culture that was just beginning to emerge in America (and abroad). The Wild One was the first “biker picture” to penetrate mainstream consciousness, a genre that would become very popular in independent film ten lean years later.

Though that amazing string of performances in A Streetcar Named Desire, Viva Zapata!, Julius Caesar, and On the Waterfront earned Marlon Brando four straight Oscar nominations (finally winning for Waterfront) and made him the most celebrated acting talent of his generation, it’s actually his work as Johnny in The Wild One that made him an icon of rebellion and helped inspire the youth culture that was just beginning to emerge in America (and abroad). The Wild One was the first “biker picture” to penetrate mainstream consciousness, a genre that would become very popular in independent film ten lean years later.

Though produced by issue-director/producer Stanley Kramer, giving the film an overly dramatic “this is important” vibe, it’s actually a really fun B-movie, carried by Brando’s cocky performance. His Johnny leads his biker gang almost like a cult leader. The gang, with their rowdy antics, tries to impress their messiah, but Johnny, with his southern/ be-bop accent, is a man of few words. Hitting the road looking for kicks, Brando and his gang stumble on a small town where they instantly catch the attention of the law and some uptight citizens, and a saloon owner invites them to stay for beer and sandwiches. The innocent young barmaid Kathie (the very beautiful Mary Murphy) catches Johnny’s eye. It doesn’t help when he declares “I don’t like cops,” even though her dad is the town’s sheriff (Robert Keith, father of Brian), and is actually very evenhanded and sympathetic to Johnny and his pals.

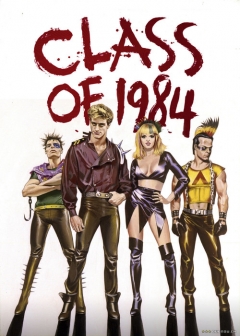

Class of 1984

As a remake of Blackboard Jungle, with a lot of A Clockwork Orange thrown in, the ’82 punk rock revenge flick Class of 1984 is still a surprisingly effective piece of exploitation pulp. With a theme song called “I Am the Future” sung by Alice Cooper (shockingly written by long time film and TV composer Lalo Schifrin!) prophetically announcing its intentions— this is a new youth nightmare. Entering the school through metal detectors (now a standard in many urban schools) the hero/teacher in this story, Andrew Norris (Perry King), is shocked at the conditions at his new school, and the kids are much more aggressive and nasty. Blackboard Jungle’s Glenn Ford had it easy compared to this guy. Yes, these aren’t you father’s punk kids anymore.

As a remake of Blackboard Jungle, with a lot of A Clockwork Orange thrown in, the ’82 punk rock revenge flick Class of 1984 is still a surprisingly effective piece of exploitation pulp. With a theme song called “I Am the Future” sung by Alice Cooper (shockingly written by long time film and TV composer Lalo Schifrin!) prophetically announcing its intentions— this is a new youth nightmare. Entering the school through metal detectors (now a standard in many urban schools) the hero/teacher in this story, Andrew Norris (Perry King), is shocked at the conditions at his new school, and the kids are much more aggressive and nasty. Blackboard Jungle’s Glenn Ford had it easy compared to this guy. Yes, these aren’t you father’s punk kids anymore.

Shot in Toronto, but sitting in as any mixed-race urban jungle USA, Mr. Norris just wants to teach the good kids music (including a nerdy young Michael J. Fox). But the school seems to be dominated by a punk rock gang led by its genius psychopathic pretty boy, Peter Stegman (Timothy Van Patten), who instantly takes a dislike to Norris for having the gall to want to teach while other teachers like Mr. Corrigan (Roddy McDowall) have just given up. Norris wants to put together a classical music school band and though Stegman can play the piano like that dude in Shine, Norris denies him a spot because of his bad attitude. This begins a deadly showdown between the two.

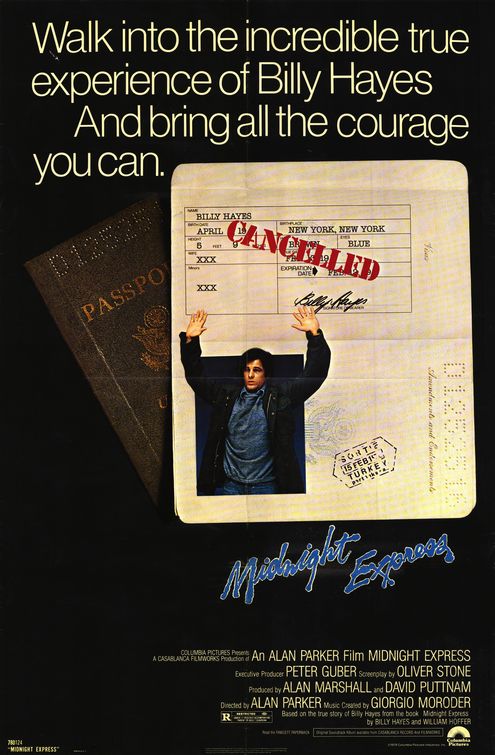

Midnight Express

In what may be the Citizen Kane of xenophobia-ploitation flicks of the ‘70s, no matter how manipulative, hateful, and offensive Midnight Express may be, it’s also some amazingly intense filmmaking. After his first feature film, the misfire kiddie musical Bugsy Malone, British director Alan Parker announced himself as a major talent with Midnight Express, as did the obscure screenwriter Oliver Stone, who won an Oscar for his adaptation of Billy Hayes’s autobiographical account of his traumatic years in a Turkish prison. Though Stone famously spiced up the account to make it even more dramatic and has since even apologized to the people of Turkey for making them look like slimy monsters, the film is still an edge-of-your-seat piece of entertainment.

In what may be the Citizen Kane of xenophobia-ploitation flicks of the ‘70s, no matter how manipulative, hateful, and offensive Midnight Express may be, it’s also some amazingly intense filmmaking. After his first feature film, the misfire kiddie musical Bugsy Malone, British director Alan Parker announced himself as a major talent with Midnight Express, as did the obscure screenwriter Oliver Stone, who won an Oscar for his adaptation of Billy Hayes’s autobiographical account of his traumatic years in a Turkish prison. Though Stone famously spiced up the account to make it even more dramatic and has since even apologized to the people of Turkey for making them look like slimy monsters, the film is still an edge-of-your-seat piece of entertainment.

Along with his compatriots Ridley Scott and Adrian Lyne, director Parker would usher in a new era of filmmakers who came out of a commercial background. Like most of his pals’ films of the era, though, Midnight Express and a number of his other films are heavy on grit and realistic detail but there still seems to be a slight gloss over their work that sometimes makes their films, no matter how gritty, look like champagne commercials. But still Parker has had a most fascinating career, peeking early with Midnight Express and then following with a run in the 1980s with Fame, Shoot the Moon, Pink Floyd The Wall, Birdy, and then Angel Heart and Mississippi Burning—all pretty good movies. But for an immigrant, it ‘s a distinctly American resume, and in some ways Midnight Express is his most American film in terms of values and the naively dim view most Americans have on the rest of the world.

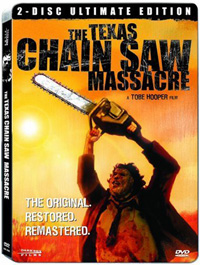

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974)

It turns out that the granddaddy of torture-porn and Slasher-poitation, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, isn’t as exploitive or graphic as its reputation would make you think. It’s actually just some good old fashioned psychological horror, much closer to the economically controlled thrills of Hitchcock than the splatter flicks of Herschell Gordon Lewis. The film is kinda-sorta based on the misdeeds of serial killer Ed Gain (also an inspiration behind the book Psycho), but perhaps more of a direct result of the graphic violence from the Vietnam War seen nightly on television news. The Texas Chainsaw Massacre may have a set-up that now seems overly familiar, but where it goes was wholly original and how it gets there is utterly horrifying. Shot in a docudrama style, its ultra realistic feel makes it seem even more real; it’s like The Battle Of Algiers meets The Hills Have Eyes.

It turns out that the granddaddy of torture-porn and Slasher-poitation, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, isn’t as exploitive or graphic as its reputation would make you think. It’s actually just some good old fashioned psychological horror, much closer to the economically controlled thrills of Hitchcock than the splatter flicks of Herschell Gordon Lewis. The film is kinda-sorta based on the misdeeds of serial killer Ed Gain (also an inspiration behind the book Psycho), but perhaps more of a direct result of the graphic violence from the Vietnam War seen nightly on television news. The Texas Chainsaw Massacre may have a set-up that now seems overly familiar, but where it goes was wholly original and how it gets there is utterly horrifying. Shot in a docudrama style, its ultra realistic feel makes it seem even more real; it’s like The Battle Of Algiers meets The Hills Have Eyes.

The ultra low budget flick opens with a somber voice-over narration (read by John Larroquette) announcing that the film is all true (and also giving the impression that it’s deeply important). Sally Hardesty (Marilyn Burns) and her group of groovy twenty-something friends in their mystery-machine like van are on their way to visit her rural grandfather’s house. Stupidly they pick up a straight razor wielding loony (Edwin Neal) who should have been the first warning that this is one part of Texas you might be advised to stay out of. Eventually they each make their way to a creepy old farmhouse nearby where they are killed off, except for Sally; as the last survivor she’s in for a long night of terror.