Night Catches Us

The low-budget period piece, Night Catches Us, is a rare kind of film these days - a complex, quiet, adult drama. More rare it’s about black people, and though it’s intense, the intensity comes from the characters' personal torment, not on-screen violence. In a perfect world Night Catches Us would catapult its first time feature director, Tanya Hamilton, as a major new relevant voice in film, but unfortunately there are no robots or superheroes in this story. The two lead performances by Anthony Mackie and Kerry Washington reaffirm their standing as two of the most reliable actors of their generation.

The low-budget period piece, Night Catches Us, is a rare kind of film these days - a complex, quiet, adult drama. More rare it’s about black people, and though it’s intense, the intensity comes from the characters' personal torment, not on-screen violence. In a perfect world Night Catches Us would catapult its first time feature director, Tanya Hamilton, as a major new relevant voice in film, but unfortunately there are no robots or superheroes in this story. The two lead performances by Anthony Mackie and Kerry Washington reaffirm their standing as two of the most reliable actors of their generation.

What happened to the “Movement” and how does that generation of black revolutionaries learn to live in a world after the revolution has fizzled out? The film slowly opens up and unfolds. It’s 1976, after years of being in exile as a snitch, ex-Black Panther Marcus Washington (Mackie) returns to his Philadelphia neighborhood to confront his past. The word on the street was that he got his best friend killed by the cops, which makes him an enemy to the folks in the hood, except that friend’s ex-wife Patricia Wilson (Washington). Also once a radical, she’s now a respectable lawyer raising a daughter as a single mother. She and Marcus seem to have something between them. Is that why her husband was killed? Or are they both just haunted by the death of a man and the loss of a way of life? What's left to fight for or stand for? These are two people lost in the past desperate to find a future. Though they do come together, there are too many ghosts between them to let them really fall in love, which in an Ibsen-like twist is what creates their bond.

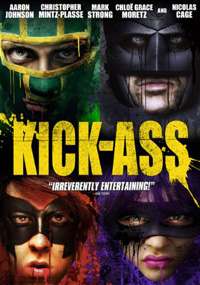

Kick-Ass

Though there’s already been about a dozen since and dozens more to come, Kick-Ass could be considered the final word on the superhero movie; it neatly puts an end to the myth and redefines the genre perfectly. Based on a comic book by Mark Millar and John Romita Jr., and directed by Matthew Vaughn (Layer Cake, X-Men: First Class), Kick-Ass is vivaciously violent and proudly R-rated. It plays as both an action movie and a send-up of the clichés of superheroes and vigilantes flicks. But this is no Hero At Large (a lame John Ritter would-be superhero flick from 1980), though it's humorous and ultra creative, by the end its grim tone moves it closer to the V For Vendetta or even Watchmen heaviness territory.

Though there’s already been about a dozen since and dozens more to come, Kick-Ass could be considered the final word on the superhero movie; it neatly puts an end to the myth and redefines the genre perfectly. Based on a comic book by Mark Millar and John Romita Jr., and directed by Matthew Vaughn (Layer Cake, X-Men: First Class), Kick-Ass is vivaciously violent and proudly R-rated. It plays as both an action movie and a send-up of the clichés of superheroes and vigilantes flicks. But this is no Hero At Large (a lame John Ritter would-be superhero flick from 1980), though it's humorous and ultra creative, by the end its grim tone moves it closer to the V For Vendetta or even Watchmen heaviness territory.

The film follows three separate New York kid storylines which eventually come together in a most surprising way. Teenage comic-book geek Dave Lizewski (Aaron Johnson), out of loneliness and an urge to make something of himself, dons a superhero costume, names himself Kick-Ass and sets out to fight crime. His first attempt to take on street punks puts him in the hospital, the good news, though, is he comes out with some actual kinda super-powers; severe nerve damage gives him the capacity to endure extreme pain. His next go at taking on petty criminals is captured on camera and makes the antics of Kick-Ass an Internet sensation.

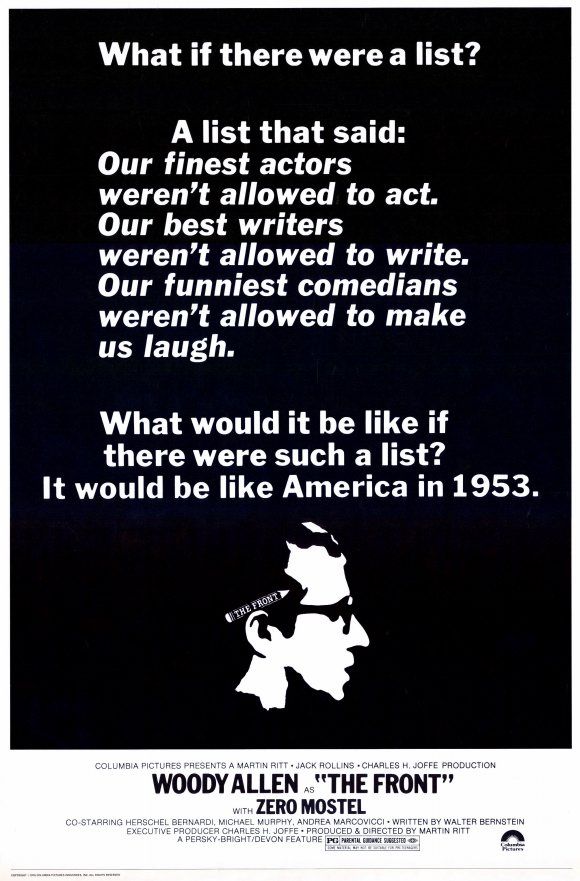

The Front

During one of the ugliest periods in American political history, as the Cold War hit hysteria, a drunk congressman named Joseph McCarthy managed to destroys thousands of American lives and careers with his House Un-American Activities Committee. HUAC would accuse people of being Communists (many of the accused at one time may have belonged to the then totally legal Communist Party or donated to causes that were Russian-related—this was years earlier when Russia was our ally against Germany). To clear your name you needed to name names and praise HUAC. Most famously many in Hollywood (almost always Jewish folks) were called to testify; some played ball with McCarthy and were considered “friendly witnesses” (Sterling Hayden, Elia Kazan) while many others refused to testify and either went to jail or were blacklisted from working.

During one of the ugliest periods in American political history, as the Cold War hit hysteria, a drunk congressman named Joseph McCarthy managed to destroys thousands of American lives and careers with his House Un-American Activities Committee. HUAC would accuse people of being Communists (many of the accused at one time may have belonged to the then totally legal Communist Party or donated to causes that were Russian-related—this was years earlier when Russia was our ally against Germany). To clear your name you needed to name names and praise HUAC. Most famously many in Hollywood (almost always Jewish folks) were called to testify; some played ball with McCarthy and were considered “friendly witnesses” (Sterling Hayden, Elia Kazan) while many others refused to testify and either went to jail or were blacklisted from working.

Screenwriter Walter Bernstein was one of those blacklisted, but by the end of the ‘50s many gutsy producers began to break the blacklist by hiring the recently unemployable. Bernstein made a comeback writing the script for Fail-Safe and eventually wrote The Front, a semiautobiographical memoir of the period. Besides Bernstein the film is full of blacklisted talent on both sides of the camera, including actor Zero Mostel and Director Martin Ritt (Hud, Norma Rae).

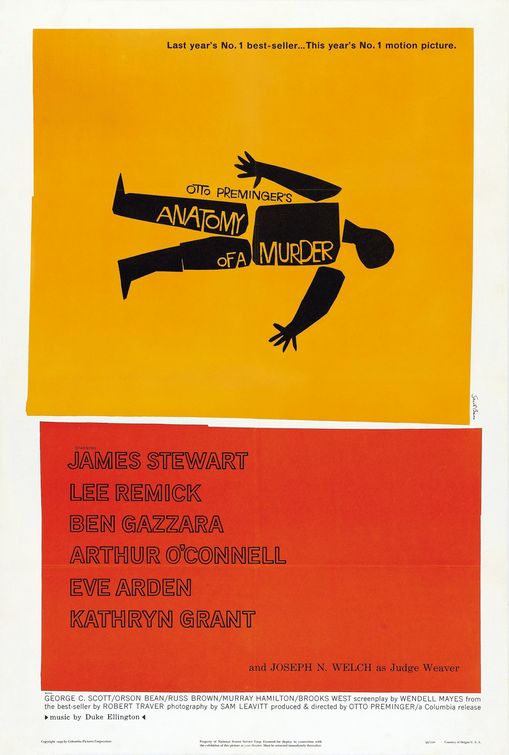

Anatomy of a Murder

Director Otto Preminger seemed to look for controversial subjects all through his career but with his two hour and forty minute courtroom masterpiece Anatomy of a Murder, he might’ve gone farther than 1959 audiences could handle. The film is about a lawyer defending a man who’s accused of killing a guy who possibly raped his wife. If that wasn’t lurid enough for audiences, they especially got all angsty over a word that was repeated in the trial, that horrific word…. “panties” (you know, women’s underwear). For anyone who can get past such a lewd word, Anatomy of a Murder is very dense in detail, almost an epic in just exploring the small details of a legal case. And it’s still one of the best lawyer flicks ever.

Director Otto Preminger seemed to look for controversial subjects all through his career but with his two hour and forty minute courtroom masterpiece Anatomy of a Murder, he might’ve gone farther than 1959 audiences could handle. The film is about a lawyer defending a man who’s accused of killing a guy who possibly raped his wife. If that wasn’t lurid enough for audiences, they especially got all angsty over a word that was repeated in the trial, that horrific word…. “panties” (you know, women’s underwear). For anyone who can get past such a lewd word, Anatomy of a Murder is very dense in detail, almost an epic in just exploring the small details of a legal case. And it’s still one of the best lawyer flicks ever.

The film is loaded with talent on both sides of the camera including a famous title sequence by Saul Bass (Psycho) and a catchy score by Duke Ellington (strange since the film takes place in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula—not exactly a “jazzy” part of the country. Also, Duke appears in a cameo as well.) Michigan Supreme Court Justice John D. Voelker wrote the book based on a real life case; the script was shrewdly adapted by Wendell Mayes (The Poseidon Adventure, Death Wish). It’s also shot in cool black & white by the dependable cinematographer Sam Leavitt (A Star Is Born, Exodus, Major Dundee) and it was edited by another pro, Louis R. Loeffler (Laura, The Long Hot Summer). And of course director/producer, the Hungarian-born Preminger himself, was one of the big guns of his era, with a directing career going back to the Noir period (Laura, Whirlpool). Anatomy of a Murder was easily his best film but everything he did, no matter the overall quality, was always interesting.

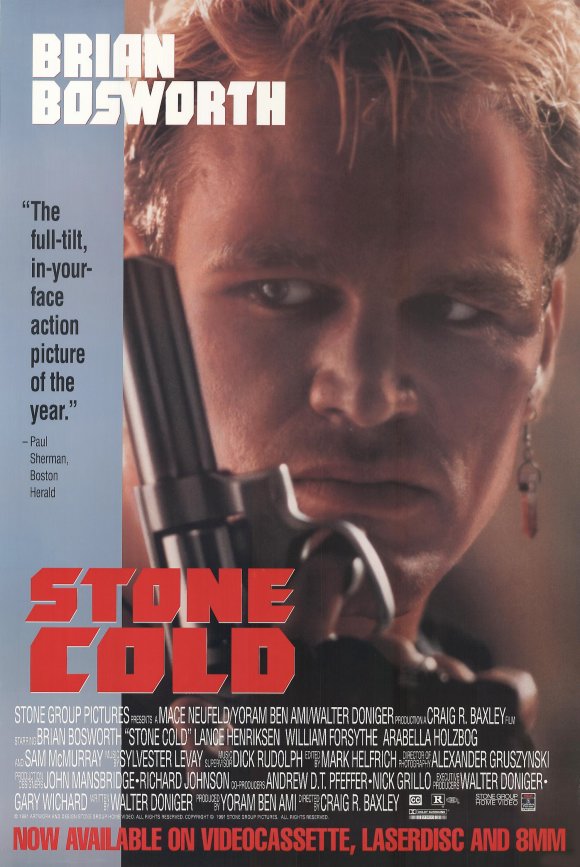

Stone Cold

Like Romeo & Juliet before it, the basic premise of Stone Cold has been recycled dozens of times since its release (Point Break, Good Cops Don’t Cry, The Fast and the Furious). Does this sound familiar? A maverick cop goes undercover into a dangerous criminal underworld and, under the spell of the bad guy’s charismatic leader, maybe gets in a little too deep. Skipping the Actors Studio or some other pansy thespian training, Brian “The Boz” Bosworth learned his acting ropes on the NFL field. At one time he was a big football star; with his way-out mullet dos and crazy sunglasses he was a sorta steroid version of David Lee Roth.

Like Romeo & Juliet before it, the basic premise of Stone Cold has been recycled dozens of times since its release (Point Break, Good Cops Don’t Cry, The Fast and the Furious). Does this sound familiar? A maverick cop goes undercover into a dangerous criminal underworld and, under the spell of the bad guy’s charismatic leader, maybe gets in a little too deep. Skipping the Actors Studio or some other pansy thespian training, Brian “The Boz” Bosworth learned his acting ropes on the NFL field. At one time he was a big football star; with his way-out mullet dos and crazy sunglasses he was a sorta steroid version of David Lee Roth.

Joe Huff (Bosworth) is a loner cop who plays by his own rules. He’s stone cold, not just because he wears stonewash jeans, but also because underneath his long black dusters he’s fearless, with almost a death wish. After being blackmailed by a prick Fed (Sam McMurray), Huff is forced to infiltrate a tough, beer- drinking biker gang who've killed a judge and been involved in all kinds of naughty activity. No longer Huff, The Boz opts for the kickass undercover name Stone. To get to the big dog, Chains Cooper (Lance Henrikson), Huff has to get past his second-in-command, the psychotic Ice (William Forsythe). And as the formula goes, Chains, though a scary dude, starts to trust Huff, and even encourages his old lady, Nancy (Arabella Holzbog), to have a go at him, but his Lieutenant Ice smells a rat.

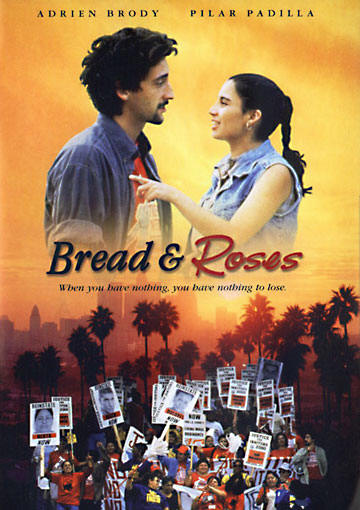

Bread & Roses

Once upon a time in Los Angeles, in the 1990s, the biggest labor strife to hit the town in fifty years was the janitor’s service union strike, a group made up of mostly legal and illegal immigrants from south of the border (giving it an especially underdog meaning). The great British “kitchen sink realism” director Ken Loach (Riff-Raff, The Wind That Shakes the Barley) came and made Bread &Roses—a very special film that uses the labor dispute as a backdrop and in doing so made one of the best films in years about both Los Angeles and the immigrant experience.

Once upon a time in Los Angeles, in the 1990s, the biggest labor strife to hit the town in fifty years was the janitor’s service union strike, a group made up of mostly legal and illegal immigrants from south of the border (giving it an especially underdog meaning). The great British “kitchen sink realism” director Ken Loach (Riff-Raff, The Wind That Shakes the Barley) came and made Bread &Roses—a very special film that uses the labor dispute as a backdrop and in doing so made one of the best films in years about both Los Angeles and the immigrant experience.

Looking for work, Maya (Pilar Padilla) sneaks into the country, joining her sister Rosa (Elpidia Carrillo) who is legal (married to an American). Eventually Maya gets work cleaning high-rise office buildings, but every corner she turns there seems to be someone wanting to exploit her and take advantage of her illegal status (both sexually and economically). After being befriended by labor activist Sam Shapiro (Adrien Brody), Maya eventually becomes a leader and helps to organize the union, becoming sort of a Mexican “Norma Rae.” This leads to complications with her sister, who doesn’t want to rock the boat and is already taking great chances boarding her.

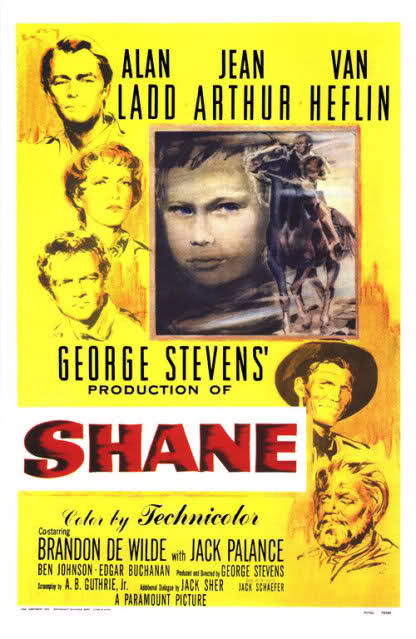

Shane

John Ford may have brought the Western out of the B-movie jungle and into the respected leagues (Stagecoach, My Darling Clementine, The Searchers, etc.), but George Stevens took the workman’s template and made it beautiful. With his masterpiece, Shane—maybe the greatest American Western of all time—he infused the genre with even more mythology than it already relied on. Shane is the film that influenced the Western Revisionists and Postmodernists more than any other; Sergio Leone and his Italian friends in the Spaghetti Western scene were all obsessed with Shane and it shows in their work. If the plot of Shane sounds familiar that’s because it’s been recycled dozens of times in everything from Westerns (Pale Rider) to post-apocalyptic junk (Steel Dawn). Shane may have more to say about the Hollywood myth and romanticism of violence, and more poetically, than any film before or since.

John Ford may have brought the Western out of the B-movie jungle and into the respected leagues (Stagecoach, My Darling Clementine, The Searchers, etc.), but George Stevens took the workman’s template and made it beautiful. With his masterpiece, Shane—maybe the greatest American Western of all time—he infused the genre with even more mythology than it already relied on. Shane is the film that influenced the Western Revisionists and Postmodernists more than any other; Sergio Leone and his Italian friends in the Spaghetti Western scene were all obsessed with Shane and it shows in their work. If the plot of Shane sounds familiar that’s because it’s been recycled dozens of times in everything from Westerns (Pale Rider) to post-apocalyptic junk (Steel Dawn). Shane may have more to say about the Hollywood myth and romanticism of violence, and more poetically, than any film before or since.

Based on the novel Shane by Jack Schaefer, the film is seen through the eyes of a young farm boy, Joey Starrett (Brandon De Wilde), in the settled territory of Wyoming. Life’s a struggle for his proud but modest parents, Joe (Van Heflin) and Marian (Jean Arthur). Besides the usual struggles against nature in the tough terrain, the area is owned by the ruthless baron, Rufus Ryker (Emile Meyer), who is trying to force the Starretts and the other local homesteaders off their land. When a drifter named Shane (Alan Ladd) shows up on horseback, the Starretts take him on as a ranch hand and he gets involved in the conflict between the wholesomely innocent homesteaders and the greedy Ryker and his posse of hired goons.

Paper Moon

Along with The Sting, Paper Moon, made a few years earlier, may be the quintessential Depression-era conman film. But while The Sting, though terrific, was more of a gimmicky star vehicle, Paper Moon has even more heart than con. In the best role of his career, Ryan O’Neal (once upon a time he was actually a superstar) stars opposite his real-life daughter Tatum O’Neal. At just eight-years-old, she gives one of the most acclaimed child performances ever. Director Peter Bogdanovich was working at the peak of his powers, fresh off the brilliant The Last Picture Show and the popular What’s Up, Doc? He vividly recreates the flat, lonely landscapes of 1930s Kansas; shooting in beautiful black & white, the period detail is as good as any modern film has ever done.

Along with The Sting, Paper Moon, made a few years earlier, may be the quintessential Depression-era conman film. But while The Sting, though terrific, was more of a gimmicky star vehicle, Paper Moon has even more heart than con. In the best role of his career, Ryan O’Neal (once upon a time he was actually a superstar) stars opposite his real-life daughter Tatum O’Neal. At just eight-years-old, she gives one of the most acclaimed child performances ever. Director Peter Bogdanovich was working at the peak of his powers, fresh off the brilliant The Last Picture Show and the popular What’s Up, Doc? He vividly recreates the flat, lonely landscapes of 1930s Kansas; shooting in beautiful black & white, the period detail is as good as any modern film has ever done.

Paper Moon is based on the novel Addie Pray by Joe David Brown (Kings Go Forth), with the screenplay by Alvin Sargent, whose massive screenwriting career ranges from Ordinary People to the recent Spider-Man sequels. Moses Pray (Ryan) is a two-bit conman. He thinks he can make a buck when, after the funeral of a one-time lover, he agrees to accompany the woman’s eight-year-old orphaned daughter, Addie (Tatum), to the train station where she will be shipped off to a distant family. She realizes that he has scammed her out of her inheritance money, so to pay him back the two end up joining up on a cross-country con job. At first they’re at odds but eventually Moses comes to realize that Addie is just as skilled at the con as him and just as cunning as and maybe even bolder than him.

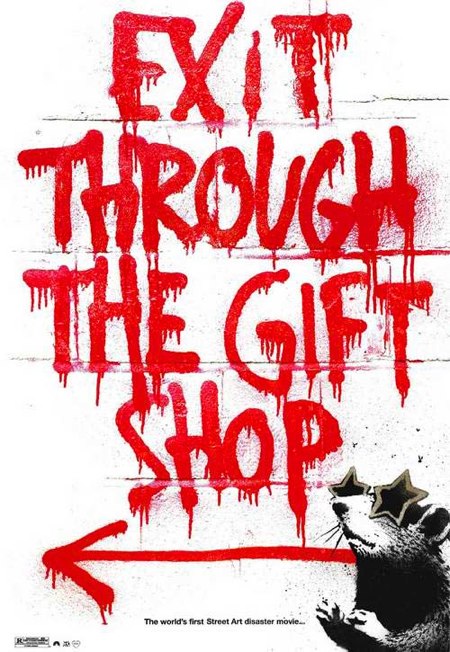

Exit Through the Gift Shop

Most of the talk surrounding Exit Through the Gift Shop was regarding whether it was a hoax or all real. But what was lost in the hoopla was what an incredibly entertaining and utterly fascinating film this documentary-within-a-

Most of the talk surrounding Exit Through the Gift Shop was regarding whether it was a hoax or all real. But what was lost in the hoopla was what an incredibly entertaining and utterly fascinating film this documentary-within-a-

Part conman, part art enthusiast, Guetta is like a bloated Pepe Le Pew. He has a bunch of kids and owns a Melrose vintage clothing store, and he constantly has a camera filming every aspect of his life. While visiting France he begins filming his cousin, a famous graffiti artist known as Invader. So begins an obsession for Guetta. Back in Hollywood he hooks up with another famous artist, Shepard Fairey (who later would become famous for his Obama “Hope” posters) and then meets loads more. He goes with them and takes part in their illegal night painting activities. When the legendary Bansky (whose real identity has never been revealed) comes to town, Guetta becomes his wingman and films all of his illegal art installations. Guetta then travels with him to London and back to LA where he serves as lookout for a stunt Banksy pulls in Disneyland. Eventually Bansky gives him the assignment to finally take all that footage and edit it into a film about street art. But what he puts together, a hodgepodge of images he calls Life Remote Control, it’s a total unwatchable mess.

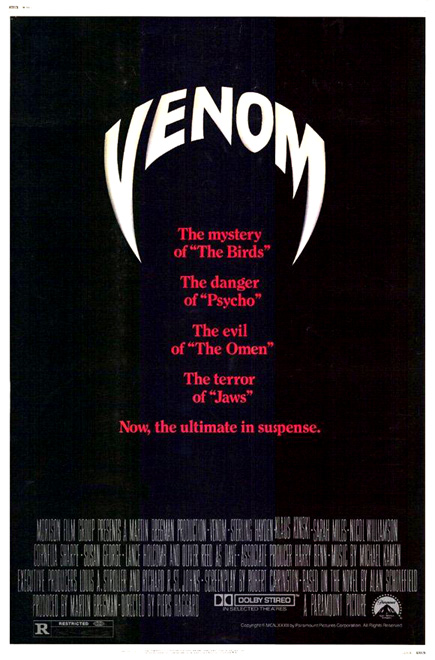

Venom

In terms of B-Movie all-star casts this crazy British flickVenom can’t be beat. All working at their highest ham level, you have the insane German method madman Klaus Kinski (Aguirre: The Wrath of God), and then there’s the American Sterling Hayden who in the fifties was a total stiff playing a lot of tough guys but then reinvented himself in the seventies as an solid character actor (The Godfather). Also on board is the great British actor Oliver Reed (The Devils) who was equally famous for his up and down career as he was for his drunken on-set behavior. Adding some more class to the cast is another terrific British actor Nicol Williamson who, other then his great performance as Merlin in Excalibur, never quite had the career he should’ve had. Rounding out the cast in the female roles, there’s swinging sixties British starlet Sarah Miles (Blow-Up), fashion-model-turned-actress Cornelia Sharpe (Serpico) and the always sexy Susan George (Straw Dogs). For a low budget flick Irwin Allen couldn’t have assembled a cooler line-up.

In terms of B-Movie all-star casts this crazy British flickVenom can’t be beat. All working at their highest ham level, you have the insane German method madman Klaus Kinski (Aguirre: The Wrath of God), and then there’s the American Sterling Hayden who in the fifties was a total stiff playing a lot of tough guys but then reinvented himself in the seventies as an solid character actor (The Godfather). Also on board is the great British actor Oliver Reed (The Devils) who was equally famous for his up and down career as he was for his drunken on-set behavior. Adding some more class to the cast is another terrific British actor Nicol Williamson who, other then his great performance as Merlin in Excalibur, never quite had the career he should’ve had. Rounding out the cast in the female roles, there’s swinging sixties British starlet Sarah Miles (Blow-Up), fashion-model-turned-actress Cornelia Sharpe (Serpico) and the always sexy Susan George (Straw Dogs). For a low budget flick Irwin Allen couldn’t have assembled a cooler line-up.

Director Piers Haggard was fresh off directing Peter Sellers’s final film, a horrible wreck called The Fiendish Plot of Dr. Fu Manchu. He replaced the American director Tobe Hooper (Texas Chainsaw Massacre) who was fired for creative reasons days into filming Venom. What’s ironic is that a few years later Hooper would make one of the craziest British genre mash-ups of all time, the zombie/alien/vampire flick Life Force. In the meantime Venom still stands as another solid genre mash-up; it’s both a kidnapping thriller and a snake-on-the-loose flick, and it does both very well.