Movies We Like

Handpicked By The Amoeba Staff

Films selected and reviewed by discerning movie buffs, television junkies, and documentary diehards (a.k.a. our staff).

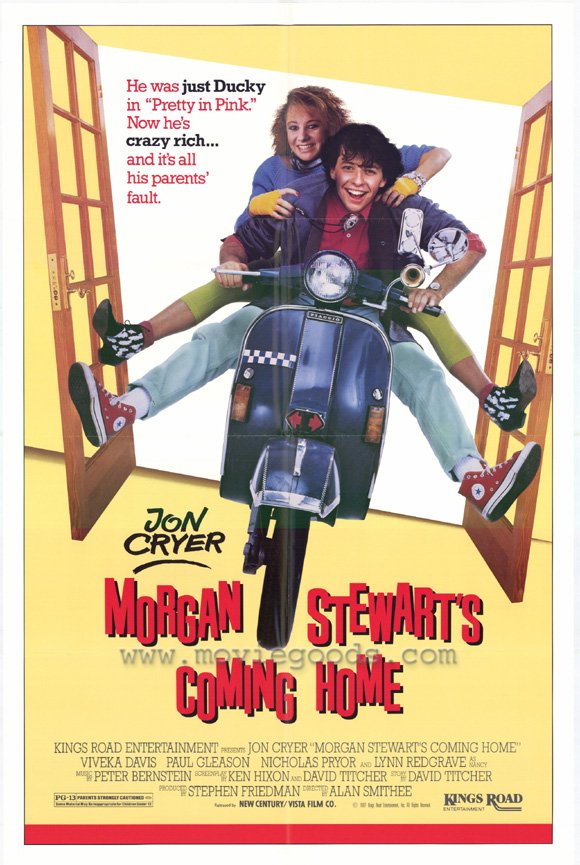

Morgan Stewart's Coming Home

Bold as it is to say, if you’re a horror fan and you appreciate the style of teen comedies that were often made in the ‘80s, then I think Morgan Stewart’s Coming Home is pretty much the most romantic movie ever made. What follows is my evidence to support this statement.

Bold as it is to say, if you’re a horror fan and you appreciate the style of teen comedies that were often made in the ‘80s, then I think Morgan Stewart’s Coming Home is pretty much the most romantic movie ever made. What follows is my evidence to support this statement.

Jon Cryer (Pretty in Pink’s Duckie, as most of you know him) plays 16-year-old Morgan Stewart, a sweet prankster currently serving time at his 10th prep school who just also happens to be a huge horror fanatic. The opening shot of the movie starts out on a close-up of his vintage theatrical one-sheet poster for Lucio Fulci’s Zombi and then pulls out and pans across his room to reveal a barrage of masks, a mechanic moving severed hand, and a slew of posters ranging from Dawn of the Dead to Tales of Terror to The Exorcist. He ends up meeting the girl of his dreams, Emily, (Viveka Davis) while waiting in line at a mall to get George A. Romero’s autograph. She insists on being called “Em,” “just like in Dial M for Murder, the only film Hitchcock ever did in 3D.” Their first date is to see a late night screening of Attack of the Killer Tomatoes. Hell, even Em’s parents are cool and give her crap over her choice of a date movie, "when William Castle’s Strait Jacket is playing at the Inner Circle!" (And clearly it’s the better choice.) She convinces Morgan to jump into the shower with her while wearing Halloween masks in a wonderful nod to Psycho, which of course always warms my black and bitter little heart. See? Most romantic movie ever, right? Oh wait; there is a story and a plot here, too!

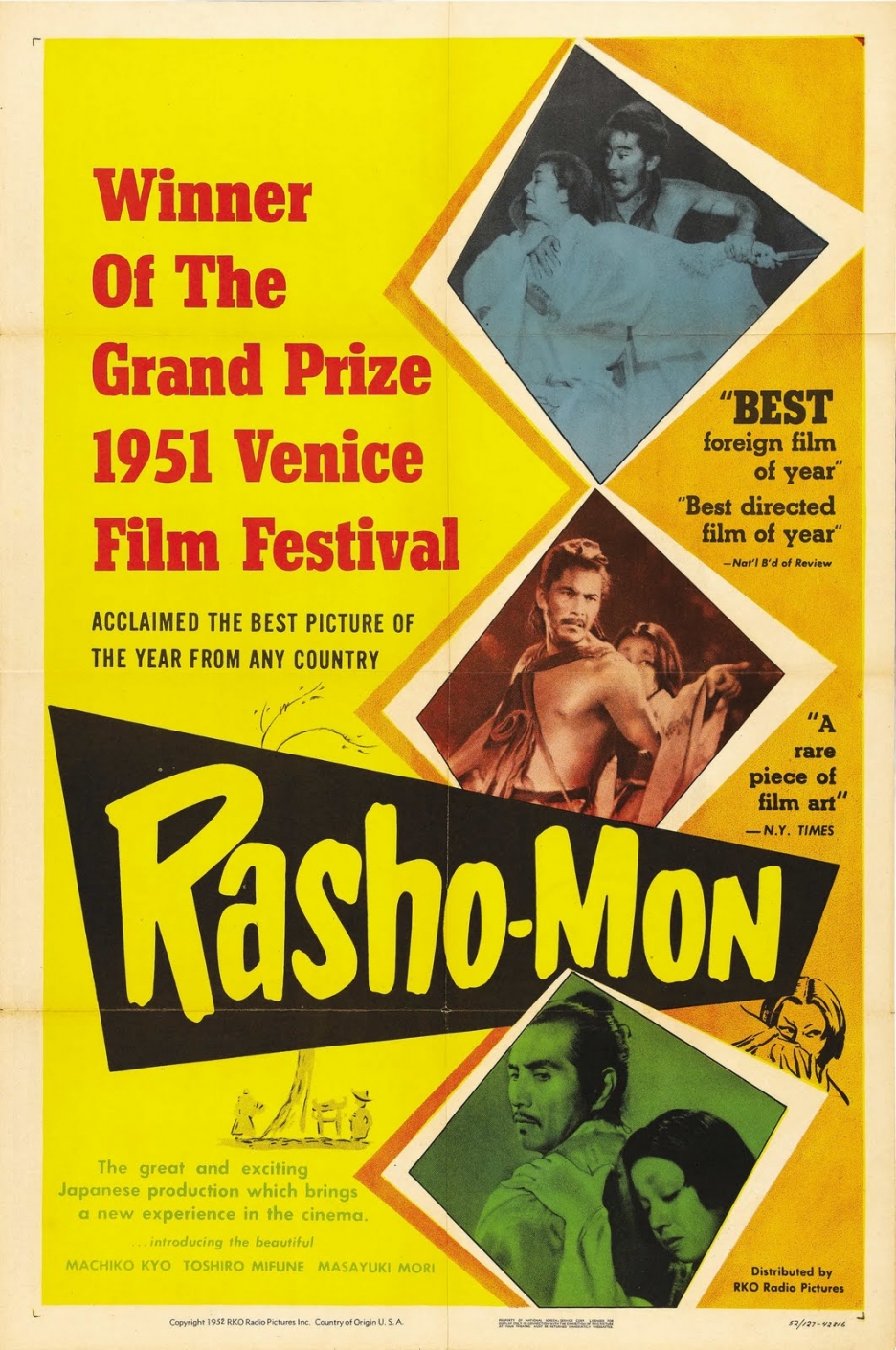

Rashomon

"It's human to lie. Most of the time we can't even be honest with ourselves."

"It's human to lie. Most of the time we can't even be honest with ourselves."

—The skeptical commoner's response to the conflicting testimonies sums up the plight of man in Akira Kurosawa's multilayered film.

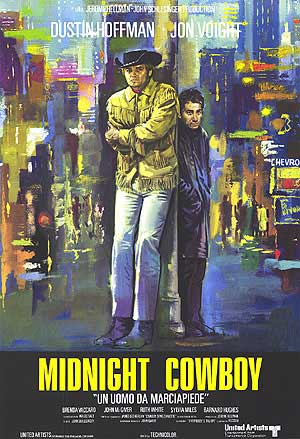

Midnight Cowboy

Though “X-rated” means something different than it did in 1969, it’s still a badge of honor that Midnight Cowboy is the only film with that “for adults only” label to have won the Best Picture Oscar (Last Tango in Paris being the other great “X-rated” flick of the era). Midnight Cowboy is less shocking today; sexually, it’s not the graphic images that provide the punch it’s the intellectually complicated nature of the characters’ sexuality that still can move an audience. As a follow up to The Graduate, Dustin Hoffman proved he was more than a one-hit wonder and instead that he had a long and vital career ahead of him. It also deservedly made a star out of a little known pretty-boy actor named Jon Voight. And it also put British director John Schlesinger on the American A-list, a guy whose deep sensitivity and open homosexuality put him ahead of his time. The film’s theme song, “Everybody’s Talkin’” performed by Harry Nilsson, has become the iconic standard bearer for images of a lonely guy walking the streets of New York. Midnight Cowboy also is a fascinating peek at an era both for representation for how an artist works at a time when the movie studios were willing to take a chance on a grubby flick about a would-be male prostitute and his new BFF while also revealing a dark side to the Big Apple during what has sometimes been considered a golden age of self-expression.

Though “X-rated” means something different than it did in 1969, it’s still a badge of honor that Midnight Cowboy is the only film with that “for adults only” label to have won the Best Picture Oscar (Last Tango in Paris being the other great “X-rated” flick of the era). Midnight Cowboy is less shocking today; sexually, it’s not the graphic images that provide the punch it’s the intellectually complicated nature of the characters’ sexuality that still can move an audience. As a follow up to The Graduate, Dustin Hoffman proved he was more than a one-hit wonder and instead that he had a long and vital career ahead of him. It also deservedly made a star out of a little known pretty-boy actor named Jon Voight. And it also put British director John Schlesinger on the American A-list, a guy whose deep sensitivity and open homosexuality put him ahead of his time. The film’s theme song, “Everybody’s Talkin’” performed by Harry Nilsson, has become the iconic standard bearer for images of a lonely guy walking the streets of New York. Midnight Cowboy also is a fascinating peek at an era both for representation for how an artist works at a time when the movie studios were willing to take a chance on a grubby flick about a would-be male prostitute and his new BFF while also revealing a dark side to the Big Apple during what has sometimes been considered a golden age of self-expression.

Apparently screenwriter Waldo Salt (who was just emerging from two decades of being blacklisted) took a lot of liberties with James Leo Herlihy’s underground but acclaimed novel. A Texas dishwasher named Joe Buck (Voight) decides to drop his apron and take advantage of his good looks; he busses up to Manhattan under the illusion that it’s a city full of rich women and fairies. They need a real cowboy to show them what a true man is. Unfortunately life in the big city doesn’t turn out like he hoped. There’s competition in the cowboy hustler department and most people are not charmed by his act. He does finally hook up with a seemingly wealthy older woman but when he requests payment for his services, she turns the tables and he ends up paying her. Similar trysts with two men, a religious nut and a teenage boy (a young Bob Balaban), prove fruitless as Joe is kicked out of his pad and finds himself cold, hungry, and homeless.

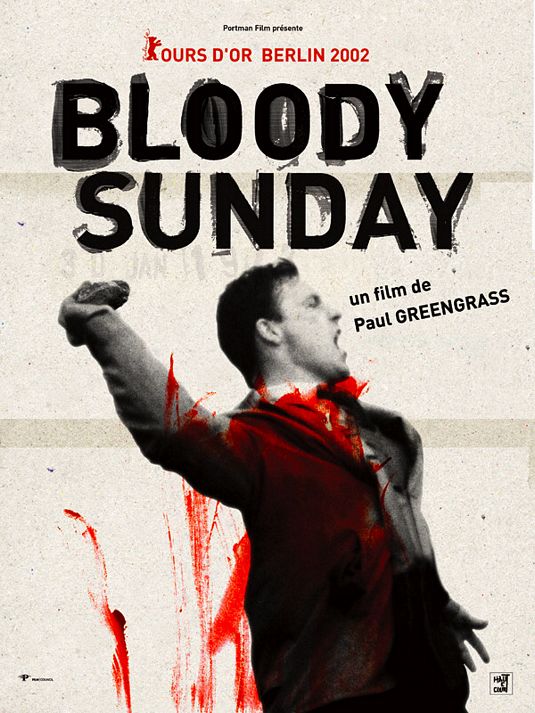

Bloody Sunday

One of the best examples of docu-realism in the Battle of Algiers-mode, Bloody Sunday, from director and writer Paul Greengrass, was originally made for Granada Television (a high quality UK outfit) but after an acclaimed screening at the Sundance Film Festival it got its theatrical run and instantly made Greeengrass a director in high demand. He went on to direct the final two Bourne flicks as well as another outstanding docu-drama, United 93. Bloody Sunday tensely recreates the events of the 1972 peace march in the Bogside of Derry, Northern Ireland that spiraled out of control as itchy trigger fingered British paratroopers opened fire on marchers killing 14 and then covering their own actions. The film tries to show the points of view of both sides, but no matter how even-handed the film intended to be, and even with the usual IRA types running around looking for a fight, it’s impossible to see it as anything less than a British massacre of the innocent.

One of the best examples of docu-realism in the Battle of Algiers-mode, Bloody Sunday, from director and writer Paul Greengrass, was originally made for Granada Television (a high quality UK outfit) but after an acclaimed screening at the Sundance Film Festival it got its theatrical run and instantly made Greeengrass a director in high demand. He went on to direct the final two Bourne flicks as well as another outstanding docu-drama, United 93. Bloody Sunday tensely recreates the events of the 1972 peace march in the Bogside of Derry, Northern Ireland that spiraled out of control as itchy trigger fingered British paratroopers opened fire on marchers killing 14 and then covering their own actions. The film tries to show the points of view of both sides, but no matter how even-handed the film intended to be, and even with the usual IRA types running around looking for a fight, it’s impossible to see it as anything less than a British massacre of the innocent.

Inspired by the American civil rights movement, the Catholics of Northern Ireland lived in a near police state under British control; the marchers even used “We Shall Overcome” as their theme song. The march was led by their local MP, Ivan Cooper, ironically a Protestant himself leading a peaceful Catholic rebellion. As played brilliantly by James Nesbitt, Cooper is the epitome of good intentions in a bad situation; he often references his idol Martin Luther King and does everything he can do to keep his marchers peaceful, but unfortunately for him this is Northern Ireland not Selma. The Northern Ireland-born Nesbitt, a staple on UK TV, was mostly known for lightweight fare like the show Cold Feet; here he gives the performance of his career. It’s a stunning piece of acting; Cooper is desperate to lead, but the weight of events is just too overpowering for him and Nesbitt earns the viewer’s respect while our hearts go out to him.

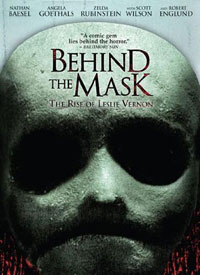

Behind The Mask: The Rise Of Leslie Vernon

If you ever sought to find a modern day horror film that both celebrated and homaged the great "slasher" era of the '80s, while simultaneously adding something new, fresh and unique to that particular sub-genre, then you need look no further than Behind The Mask: The Rise Of Leslie Vernon.

If you ever sought to find a modern day horror film that both celebrated and homaged the great "slasher" era of the '80s, while simultaneously adding something new, fresh and unique to that particular sub-genre, then you need look no further than Behind The Mask: The Rise Of Leslie Vernon.

In the world of the film, our modern day real life boogeymen don’t exist. There’s no Charles Manson or John Wayne Gacy or Jeffrey Dahmer. But the cinematic baddies that we’re all well versed in – Freddy Krueger, Jason Voorhees, Michael Myers – all exist in the world of Behind The Mask. They are in fact folklore. Camp fire tales. Legends. The next great killer to join their ranks, whose name will evoke terror and fear to the small, little town of Glen Echo, will be Leslie Vernon. To document both his training and first onslaught, Vernon (Nathan Baesel) has invited a small crew of college filmmakers, fronted by aspiring journalist Taylor Gentry (Angela Goethels), to join him as he becomes the sure-to-be-legendary masked maniac. The results are both frightening and hilarious.

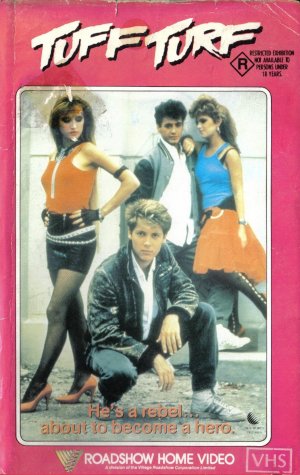

Tuff Turf

Like a stunned archaeologist I happened upon a relic from the past that may be a Holy Grail for shining light on an era and a people; it’s a little movie called Tuff Turf. Perhaps it can be used not to tell us about life in 1985 — I imagine that any relation to actual life is purely coincidental — no, it tells us more about the hack filmmakers of that period. Like so many films about young people in that period, the filmmakers are highly influenced by the worst qualities of music videos and seem intent on filling the movie with banal musical interludes. It’s a mix of Class of 1984 and Footloose (which obviously includes some Rebel without a Cause), mixing in live performances but without the skill of Streets of Fire. Yes, it’s supposed to be a gritty school gang vs. the new guy flick, but where flicks like Class of 1984 and even Bad Boys were legitimately disturbing, even with some heavy moments of violence Tuff Turf carries the influential stamp of Grease 2, or worse, ‘60s beach movies. There’s actually a shocking moment when the kids break out in a spontaneous, highly choreographed dance number (no, really); any state of edge in the film is an accident. Oh, and the editing and timing are completely stilted and awkward. However, these minor grievances aside, Tuff Turf is a bad film; as a matter of fact its severe mediocrity actually makes it all the more fascinating and entertaining.

Like a stunned archaeologist I happened upon a relic from the past that may be a Holy Grail for shining light on an era and a people; it’s a little movie called Tuff Turf. Perhaps it can be used not to tell us about life in 1985 — I imagine that any relation to actual life is purely coincidental — no, it tells us more about the hack filmmakers of that period. Like so many films about young people in that period, the filmmakers are highly influenced by the worst qualities of music videos and seem intent on filling the movie with banal musical interludes. It’s a mix of Class of 1984 and Footloose (which obviously includes some Rebel without a Cause), mixing in live performances but without the skill of Streets of Fire. Yes, it’s supposed to be a gritty school gang vs. the new guy flick, but where flicks like Class of 1984 and even Bad Boys were legitimately disturbing, even with some heavy moments of violence Tuff Turf carries the influential stamp of Grease 2, or worse, ‘60s beach movies. There’s actually a shocking moment when the kids break out in a spontaneous, highly choreographed dance number (no, really); any state of edge in the film is an accident. Oh, and the editing and timing are completely stilted and awkward. However, these minor grievances aside, Tuff Turf is a bad film; as a matter of fact its severe mediocrity actually makes it all the more fascinating and entertaining.

Understanding what motivates the lead character Morgan Hiller is a challenge for viewers because he’s played by a young James Spader, who even in his best performance (Sex, Lies, and Videotape) can come off as aloof and odd, as if he’s Christopher Walken’s prettier younger brother. After a long music video credit sequence, the film opens with a group of Los Angeles Valley teen toughs straight out of Michael Jackson’s “Beat It” video, mugging a civilian. The hair-sprayed bandanna gang is led by big-chested Nick (thirty-something looking Paul Mones) and his devoted main squeeze, Frankie (child star later turned reality TV mess, Kim Richards). Morgan rides his bike, whistling past the gang spray painting their faces and ruining their crime. Is he some kind of teen vigilante? Nope, just an East Coast rich kid who relocated to L.A. after his family fortune went bust. Now this former prep school rebel has to figure out how to fit in at a rough public school; it didn’t help to make enemies with Nick and his crew. Even after they publicly mess up his bicycle the nearly fearless Morgan continues to woo the much more “street” Frankie, pushing Nick’s wrath even further.

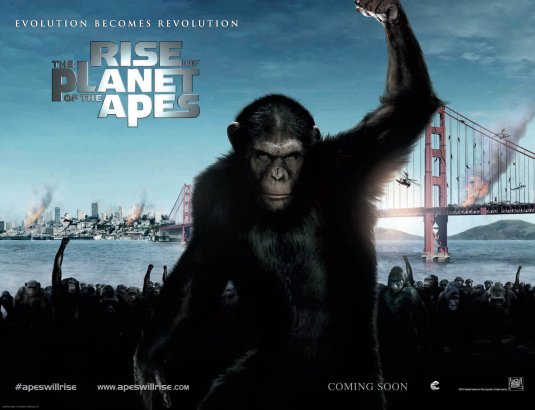

Rise of the Planet of the Apes

When the legacy of a film that you a feel deep affection for is messed with the knee-jerk reaction can be negative; every once in a while a remake can be respected (Dawn of the Dead) or a sequel can outdo the original (The Road Warrior, Aliens) but most sequels and remakes are strictly quick buck affairs. So there’s no point in getting snotty about Rise of the Planet of the Apes; it’s a big, fun, flawed but intelligent reimagining of the series. It’s the best Apes flick since the original film, Planet of the Apes in 1968, one of my all-time favorite movies. The legacy has already been contaminated; the quality of the four sequels (Beneath…, Escape from…, Conquest of…, and Battle for…) vary in quality. Both the live action and animated television series, based on the film, are amazingly boring. And Tim Burton’s ill-conceived remake was a dud. Frankly, fans of Pierre Boulle’s original book have the most to complain about as the ‘68 version’s screenwriters, Rod Serling and Michael Wilson, hit the bull’s-eye, but completely abandoned much of the novel’s concept. The rebooting of a stale series has done wonders in recent years for both Batman and James Bond; rebooting as opposed to remaking looks to be the new way to find new creative angles.

When the legacy of a film that you a feel deep affection for is messed with the knee-jerk reaction can be negative; every once in a while a remake can be respected (Dawn of the Dead) or a sequel can outdo the original (The Road Warrior, Aliens) but most sequels and remakes are strictly quick buck affairs. So there’s no point in getting snotty about Rise of the Planet of the Apes; it’s a big, fun, flawed but intelligent reimagining of the series. It’s the best Apes flick since the original film, Planet of the Apes in 1968, one of my all-time favorite movies. The legacy has already been contaminated; the quality of the four sequels (Beneath…, Escape from…, Conquest of…, and Battle for…) vary in quality. Both the live action and animated television series, based on the film, are amazingly boring. And Tim Burton’s ill-conceived remake was a dud. Frankly, fans of Pierre Boulle’s original book have the most to complain about as the ‘68 version’s screenwriters, Rod Serling and Michael Wilson, hit the bull’s-eye, but completely abandoned much of the novel’s concept. The rebooting of a stale series has done wonders in recent years for both Batman and James Bond; rebooting as opposed to remaking looks to be the new way to find new creative angles.

The King of Marvin Gardens

"Get your ass down here fast. Our kingdom has come."

—Jason Staebler's enthusiastic message to his younger brother David characterizes the delusions of grandeur in Bob Rafelson's 1972 film.

Husbands and Wives

If Annie Hall was Woody Allen’s ode to falling in love, 15 years later Husbands and Wives is an examination of falling out of love. Where the look and style of Annie Hall was clean and precise, Husbands and Wives is franticly shot handheld with herky-jerky editing and an almost improvised vibe to the performances. If Annie Hall marked the beginning of Allen’s great run of introspective masterpieces and near masterpieces, Husbands and Wives is the end of the streak. It’s his last really important Woody Allen film and definitely his last strong acting performance before he fell into a cliché of himself or brought in other actors to substitute, aping his own famous mannerisms. Husbands and Wives doesn’t have as many laughs as some of his earlier work but the insights into relationships can be utterly nerve striking. Made during his dramatic break up with his then wife Mia Farrow, it may be the last time Allen really had something he wanted to say or was worth hearing.

If Annie Hall was Woody Allen’s ode to falling in love, 15 years later Husbands and Wives is an examination of falling out of love. Where the look and style of Annie Hall was clean and precise, Husbands and Wives is franticly shot handheld with herky-jerky editing and an almost improvised vibe to the performances. If Annie Hall marked the beginning of Allen’s great run of introspective masterpieces and near masterpieces, Husbands and Wives is the end of the streak. It’s his last really important Woody Allen film and definitely his last strong acting performance before he fell into a cliché of himself or brought in other actors to substitute, aping his own famous mannerisms. Husbands and Wives doesn’t have as many laughs as some of his earlier work but the insights into relationships can be utterly nerve striking. Made during his dramatic break up with his then wife Mia Farrow, it may be the last time Allen really had something he wanted to say or was worth hearing.

Besides the French New Wave camera work and cutting, there’s an occasional narrator and interviews with the characters; what was meant to give the film a documentary feel actually seems now to predate reality TV. Gabe (Allen), a writer and college professor, is in a stale marriage to Judy (Farrow); they are shocked when, before a dinner date, their good friends Jack (Sidney Pollack) and Sally (Judy Davis) announce their separation. Subconsciously it may expose their inner doubts about their own marriage. Jack quickly gets a much younger girlfriend, an aerobics trainer named Sam (Lysette Anthony), while Sally’s dating life is less successful until Judy introduces her to her coworker, the sweetly hunky Michael (Liam Neeson). Meanwhile Gabe and Judy argue about having a child and his indifference towards her writing aspirations. Gabe befriends a young writing student, Rain (Julliette Lewis replacing Emily Lloyd who was fired after shooting begun), with whom he finds a creative (and potentially sexual) bond that he doesn’t have with Judy. From there the couple’s relationships get worse, better, and worse.

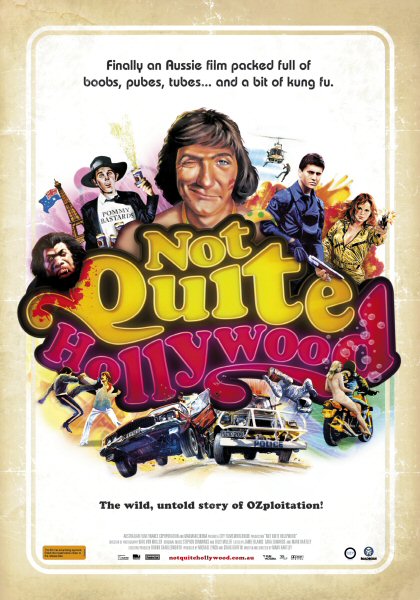

Not Quite Hollywood: The Wild, Untold Story of Ozploitation!

While Peter Weir and Fred Schepisi were putting Australian cinema on the map in the 1970s with films like Picnic at Hanging Rock and The Devil’s Playground, an amazing underworld of exploitation cinema was also happening Down Under full of sex and violence, exuberantly captured by director Mark Hartley in his slam bang documentary Not Quite Hollywood: The Wild, Untold Story of Ozploitation! Like his more recent ode to Filipino exploitation flicks, Machete Maidens Unleashed, Hartley has found the perfect formula for honoring the less honorable world cinema. Tracing Australia’s growth from sexploitation through stuntploitation and finally peaking with George Miller’s masterful Mad Max and Mad Max 2: The Road Warrior (known in the U.S. as The Road Warrior). With a plethora of wall-to-wall clips and both informative and entertaining talking heads telling the story including Quentin Tarantino, George Lazenby, Brian Trenchard-Smith, John Waters, and Richard Franklin, this movie is an absolute blast.

While Peter Weir and Fred Schepisi were putting Australian cinema on the map in the 1970s with films like Picnic at Hanging Rock and The Devil’s Playground, an amazing underworld of exploitation cinema was also happening Down Under full of sex and violence, exuberantly captured by director Mark Hartley in his slam bang documentary Not Quite Hollywood: The Wild, Untold Story of Ozploitation! Like his more recent ode to Filipino exploitation flicks, Machete Maidens Unleashed, Hartley has found the perfect formula for honoring the less honorable world cinema. Tracing Australia’s growth from sexploitation through stuntploitation and finally peaking with George Miller’s masterful Mad Max and Mad Max 2: The Road Warrior (known in the U.S. as The Road Warrior). With a plethora of wall-to-wall clips and both informative and entertaining talking heads telling the story including Quentin Tarantino, George Lazenby, Brian Trenchard-Smith, John Waters, and Richard Franklin, this movie is an absolute blast.

While films were filmed in and about Australia, they were usually films like Wake in Fright and Walkabout that were made by foreigners; originally Australia’s most popular film exports were soft porny sex comedies with such titles as The Naked Bunyip, Alvin Rides Again, and Again! And Again! And Again! and The Sex Therapist. While Australians were enjoying idiotic homemade comedies with the “Ocker” films (which crudely made fun of Australian hick values) like Alvin Purple, Stork, and The Adventures of Barry McKenzie (directed by Bruce Beresford who would eventually go more high brow with his Australian masterpiece Braker Morant).