Movies We Like

Handpicked By The Amoeba Staff

Films selected and reviewed by discerning movie buffs, television junkies, and documentary diehards (a.k.a. our staff).

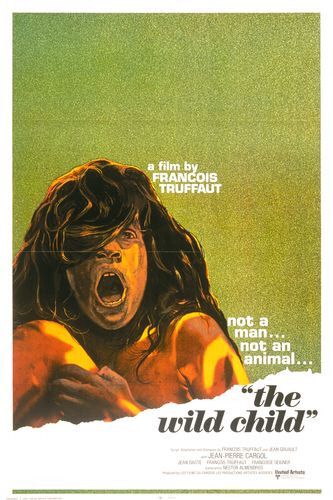

The Wild Child

"I wish that my pupil could have understood me at this moment. I would have told him that his bite filled my soul with joy."

"I wish that my pupil could have understood me at this moment. I would have told him that his bite filled my soul with joy."

—Dr. Itard reflects upon his discovery of the feral boy's sense of justice in Truffaut's 1970 film.

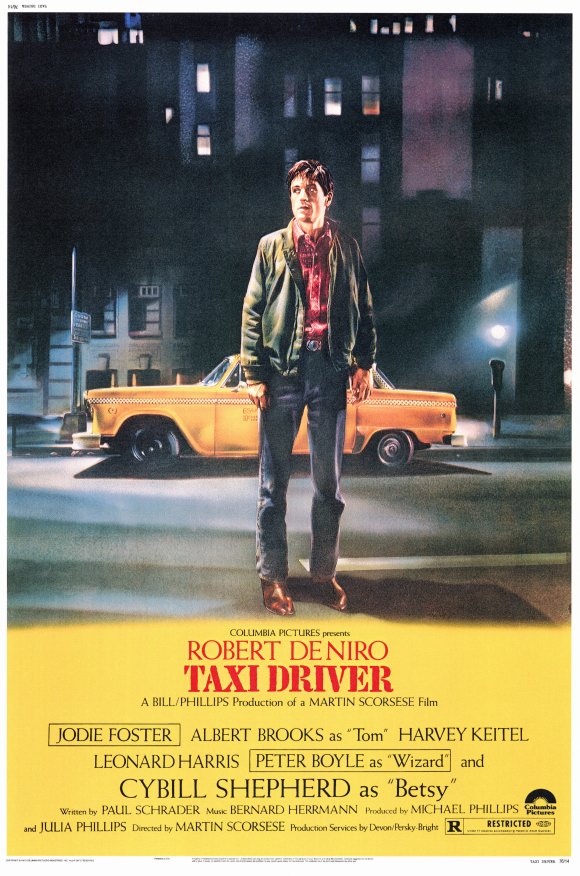

Taxi Driver

The culty acclaim of Martin Scorsese’s 1976 Taxi Driver is mostly deserved; the film is made up of some of the greatest scenes and moments of the decade. But with that there are some scenes and moments that don’t work as well. Really what Taxi Driver is is a good ol’ fashioned 70s exploitation flick, gussied up with a big-time director and cast. It’s a perfect combination of two of the era’s most potent B-movie formulas, “the crazy Vietnam vet” flick and “the New York city loner vigilante” saga. Two genres of exploitation pulp that go together like peanut butter and chocolate, after a while you can’t imagine one without the other. Like Scarlet O’Hara or Forest Gump, the name Travis Bickle has become a cultural definition of a type. Robert De Niro, at the peak of his thespian prowess, plays the lonely city taxi driver who prowls the street in search of some kind of meaning for his life. Teaming with Scorsese for the second time (after the brilliant Mean Streets, and with six more collaborations to come), it’s one of the great actor’s most iconic roles, and still a signature film for the director.

The culty acclaim of Martin Scorsese’s 1976 Taxi Driver is mostly deserved; the film is made up of some of the greatest scenes and moments of the decade. But with that there are some scenes and moments that don’t work as well. Really what Taxi Driver is is a good ol’ fashioned 70s exploitation flick, gussied up with a big-time director and cast. It’s a perfect combination of two of the era’s most potent B-movie formulas, “the crazy Vietnam vet” flick and “the New York city loner vigilante” saga. Two genres of exploitation pulp that go together like peanut butter and chocolate, after a while you can’t imagine one without the other. Like Scarlet O’Hara or Forest Gump, the name Travis Bickle has become a cultural definition of a type. Robert De Niro, at the peak of his thespian prowess, plays the lonely city taxi driver who prowls the street in search of some kind of meaning for his life. Teaming with Scorsese for the second time (after the brilliant Mean Streets, and with six more collaborations to come), it’s one of the great actor’s most iconic roles, and still a signature film for the director.

As a guy who doesn’t need sleep and doesn’t mind venturing in to the rougher sides of town, Travis is instantly hired as a cabbie. He learned some of the ropes from colleagues over late night coffee stops, led by Wizard (go-to working class character actor Peter Boyle). His clientele ranges from the high end to creeps (Scorsese in a fantastic scene), and pimps and hookers—that’s where he meets and becomes kinda obsessed with Iris (Jodie Foster), a teenage hooker who was briefly fleeing her pimp, Sport (Harvey Keitel). He also strikes up a near romance with a beautiful campaign worker, Betsy (Cybill Sheperd), who works for senator Palantine (Leonard Harris). Though her coworker (Albert Brooks) has his doubts about Travis, she agrees to go out with him. He blows it when he idiotically takes her to see a porn movie. Getting blown off by her gives him more time to fret over Iris; his obsession with her does not seem to be sexual, he just has a high moral code and feels like he can help her. And he sinks deeper into a type of self-obsessed heroic fantasy. After killing a guy who attempts to rob a grocery store his itch for more action grows so he gives himself a Mohawk hairdo and makes a feeble attempt at shooting Palantine. Instead, when that doesn’t work out he goes after Iris’s pimp, culminating in an extremely bloody shoot-out with him and the whorehouse manager in front of Iris, where he kills both of them and gets shot up himself.

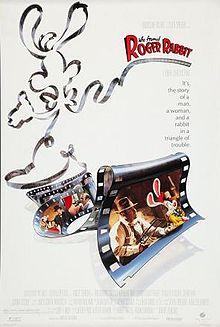

Who Framed Roger Rabbit

"The problem is I got a fifty-year-old lust and three-year-old dinky."

"The problem is I got a fifty-year-old lust and three-year-old dinky."

—Baby Herman's irreverent response to being labeled a ladies' man pushes the envelope of cartoon decency in Disney's groundbreaking film from 1988.

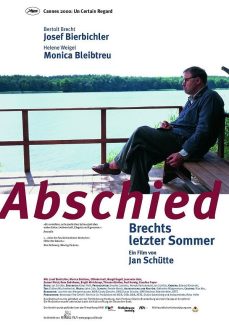

The Farewell

The Farewell is an account of the final days of the poet, playwright, and theater director, Bertolt Brecht (played by Josef Bierbichler). It recounts a single day of his vacation miles outside of Berlin where he prepared, alongside his reviser, wife, daughter, and mistresses, for the new theater season. The interests of everyone present clash on several matters, most importantly Brecht's health, which was in rapid decline. His wife Helene/Helli (Monica Bleibtreu) stands by as others dote on him. Many, including Kathe (Jeanette Hain), a young actress who seems to be his latest muse and mistress, take priority over his own wife and daughter, Barbara, in terms of attention. Also present on the estate for the vacation is Wolfgang Harich and his wife Isot. Harich is a political reformer who openly shares his wife with Brecht. To complete the picture is Elizabeth, his reviser, and Ruth, an old mistress past middle age who is now an alcoholic and an emotional wreck over the fact that Brecht no longer takes interest in her.

The Farewell is an account of the final days of the poet, playwright, and theater director, Bertolt Brecht (played by Josef Bierbichler). It recounts a single day of his vacation miles outside of Berlin where he prepared, alongside his reviser, wife, daughter, and mistresses, for the new theater season. The interests of everyone present clash on several matters, most importantly Brecht's health, which was in rapid decline. His wife Helene/Helli (Monica Bleibtreu) stands by as others dote on him. Many, including Kathe (Jeanette Hain), a young actress who seems to be his latest muse and mistress, take priority over his own wife and daughter, Barbara, in terms of attention. Also present on the estate for the vacation is Wolfgang Harich and his wife Isot. Harich is a political reformer who openly shares his wife with Brecht. To complete the picture is Elizabeth, his reviser, and Ruth, an old mistress past middle age who is now an alcoholic and an emotional wreck over the fact that Brecht no longer takes interest in her.

On the morning of their last day of vacation a Stasi officer comes calling and wishes to speak with Brecht's wife in private. He asks if the Harichs are present in their company, and once this has been confirmed, he informs Helli that by sundown they plan to arrest their friends for high treason, no doubt due to Wolfgang's radical activities. The officer asks that everyone on the estate clear out by six o’clock that evening and gives her a number to call and a signal to recite when it's safe for them to take action. He also asks her to not inform the Harichs of the arrest or their conversation, and in doing so, she will keep herself and Brecht out of danger.

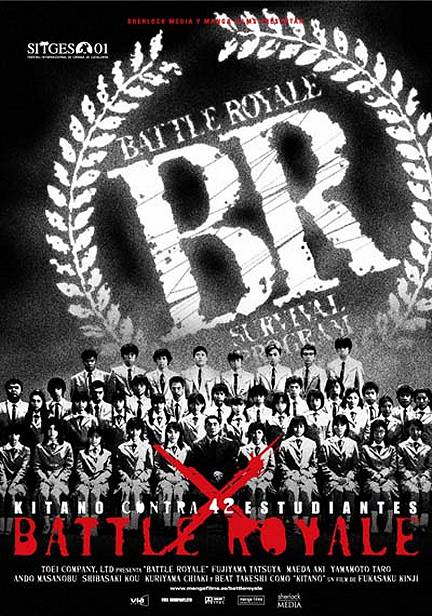

Battle Royale

It's always quite special when you can see a film on the big screen for the first time. This was especially true of Kinji Fukasaku's Battle Royale, which, until its recent run at a revival theater here in L.A., had never been given a theatrical release in the U.S. The film is in the tradition of movies such as The Most Dangerous Game, Lord of the Flies, and Punishment Park—a series of circumstances unfold that places a group of people in a deserted space to either be hunted or turned into animals in captivity who must redefine “survival of the fittest.” Besides the ultra-violence laden with dark satire, the film is unique because those playing the game are a bunch of ninth graders from modern Japan, equipped with bizarre, sometime useless tools, and forced to kill each other or be killed by their own government. Even more bizarre is that the person to initiate them into the game is a former teacher, pushed to the edge by their insolence. The final flare comes in the form of two mysterious transfer students, each a willing participant in the hunt.

It's always quite special when you can see a film on the big screen for the first time. This was especially true of Kinji Fukasaku's Battle Royale, which, until its recent run at a revival theater here in L.A., had never been given a theatrical release in the U.S. The film is in the tradition of movies such as The Most Dangerous Game, Lord of the Flies, and Punishment Park—a series of circumstances unfold that places a group of people in a deserted space to either be hunted or turned into animals in captivity who must redefine “survival of the fittest.” Besides the ultra-violence laden with dark satire, the film is unique because those playing the game are a bunch of ninth graders from modern Japan, equipped with bizarre, sometime useless tools, and forced to kill each other or be killed by their own government. Even more bizarre is that the person to initiate them into the game is a former teacher, pushed to the edge by their insolence. The final flare comes in the form of two mysterious transfer students, each a willing participant in the hunt.

The story begins with an announcement about the new BR (Battle Royale) Act, in which students will be chosen at random to be pitted against each other due to their lack of respect for adults. This announcement is followed by a glimpse of reporters shoving to get a glimpse of a young girl, the latest survivor of a BR course. We then cut to a ninth grade class that's a bit more anarchic than usual. After writing on the chalkboard that they've decided to take the day off, Noriko (Aki Maeda), a kindhearted favorite in the class, approaches her befuddled teacher Mr. Kitano (Takeshi Kitano), seeking an explanation for the absence of her peers. Kitano exits without comment only to meet a ballsy student with a knife that slashes him. The teacher leaves the school and everything returns to normal for the most part. At the end of the year the school organizes a class trip in which everyone is loaded onto a bus for a retreat, including drop outs who've come back to school just for the field trip. The knifer is one of those students, and he is close friends with Shuya (Tatsuya Fujiwara), who recently lost his father to suicide. The students are thoroughly enjoying themselves, and Noriko even gathers up the courage to approach Shuya with a bundle of cookies she's baked just for him. Everyone takes a little nap and Shuya wakes to find his peers and teacher gassed while two menacing people wearing masks navigate the bus. Once he's found awake he is knocked unconscious.

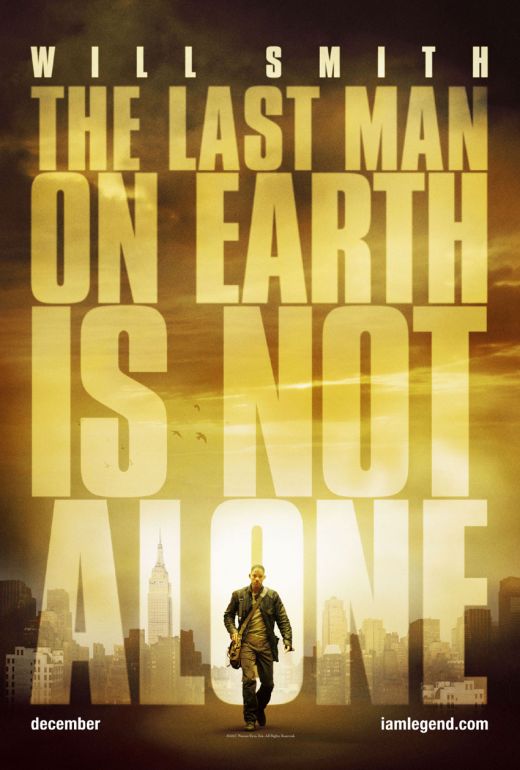

I Am Legend

Is it possible to love a movie and recommend it but still advise to turn it off just after the half-way mark? The history of films with great Act Ones and maybe even Act Twos that then fall apart by Act Three constitutes a long list (Mulholland Dr., From Dusk Till Dawn, Full Metal Jacket, etc.). I Am Legend may be the most extreme case. It has a pretty spectacular first half that’s suspenseful, exciting, but by that last act things go terribly astray. Based on the classic novelette by the great writer Richard Matheson, it had been filmed twice earlier— first in the ‘60s as a dull low-budget Vincent Price flick called The Last Man on Earth and then the culty Charlton Heston early ‘70s vehicle re-titled The Omega Man. I don’t remember ever making it all the way through the Price version, but the beloved Heston flick had the same problem as the newest take; though the whole of the ‘70s film is so goofy that the plot twist in the second half is less abrupt and problematic than in the newer more “realistic” version, they both have great set-ups that couldn’t carry through to the end.

Is it possible to love a movie and recommend it but still advise to turn it off just after the half-way mark? The history of films with great Act Ones and maybe even Act Twos that then fall apart by Act Three constitutes a long list (Mulholland Dr., From Dusk Till Dawn, Full Metal Jacket, etc.). I Am Legend may be the most extreme case. It has a pretty spectacular first half that’s suspenseful, exciting, but by that last act things go terribly astray. Based on the classic novelette by the great writer Richard Matheson, it had been filmed twice earlier— first in the ‘60s as a dull low-budget Vincent Price flick called The Last Man on Earth and then the culty Charlton Heston early ‘70s vehicle re-titled The Omega Man. I don’t remember ever making it all the way through the Price version, but the beloved Heston flick had the same problem as the newest take; though the whole of the ‘70s film is so goofy that the plot twist in the second half is less abrupt and problematic than in the newer more “realistic” version, they both have great set-ups that couldn’t carry through to the end.

The new version opens with a TV broadcasting a news show; Doctor Krippin (an uncredited Emma Thompson) declares they have engineered a virus that will cure cancer. Cut: it’s three years later and an abandoned Manhattan looks straight out of the History Channel’s Life After People; nature has taken it back with plant growth covering Times Square and wild animals now living freely on the island (using both CGI and actual redressed New York locations). Robert Neville (Will Smith) seems to be the last man alive; he speeds around Manhattan with his dog Sam (or Samantha), hunting elk, losing out on his latest prey to a pack of lions. Neville was a military scientist and had worked with the team that invented the miracle drug that eventually wiped out civilization. Though he is immune, he looks for a cure by testing lab rats in the basement lab of his Washington Square brownstone, when he’s not hitting golf balls off a aircraft carrier and broadcasting his daily radio plea for any survivors to come find him.

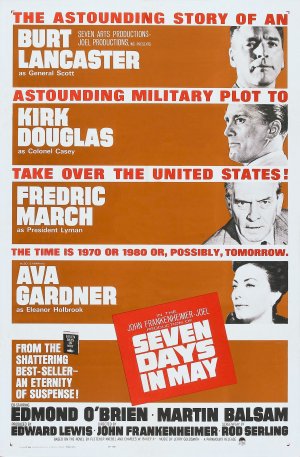

Seven Days in May

With the Cold War in full swing, the saga of President Kennedy peaking, another potential war in Asia, and nuclear proliferation moving at a rapid pace, the early ‘60s inspired a slew of solid political flicks. From nuclear madness came Fail-Safe, Dr. Strangelove, and On the Beach. Political soap operas inspired Advise & Consent and The Best Man and from those, the deep paranoia of the right, and the “military industrial complex” came director John Frankenheimer’s twisted, sorta sci-fi nightmare, The Manchurian Candidate. For Frankenheimer’s follow-up he would combine all the genres (nukes, politics and right wing paranoia) for the slick White House thriller Seven Days in May which features Burt Lancaster and Kirk Douglas appearing together for the second time, after Gunfight At The O.K. Corral (not including Lancaster’s cameo in The List of Adrian Messenger). Just as he did brilliantly in Sweet Smell of Success this time Lancaster took the supporting bad guy role. It’s a great showdown between two of Hollywood’s most sculpted physiques of their era.

With the Cold War in full swing, the saga of President Kennedy peaking, another potential war in Asia, and nuclear proliferation moving at a rapid pace, the early ‘60s inspired a slew of solid political flicks. From nuclear madness came Fail-Safe, Dr. Strangelove, and On the Beach. Political soap operas inspired Advise & Consent and The Best Man and from those, the deep paranoia of the right, and the “military industrial complex” came director John Frankenheimer’s twisted, sorta sci-fi nightmare, The Manchurian Candidate. For Frankenheimer’s follow-up he would combine all the genres (nukes, politics and right wing paranoia) for the slick White House thriller Seven Days in May which features Burt Lancaster and Kirk Douglas appearing together for the second time, after Gunfight At The O.K. Corral (not including Lancaster’s cameo in The List of Adrian Messenger). Just as he did brilliantly in Sweet Smell of Success this time Lancaster took the supporting bad guy role. It’s a great showdown between two of Hollywood’s most sculpted physiques of their era.

Based on a novel by Fletcher Knebel and Charles W. Bailey, Douglas plays Colonel Martin "Jiggs" Casey, a Pentagon Joint Chiefs of Staff aide to the powerful James Mattoon Scott (Lancaster). Jiggs is a moderate, more devoted to upholding the Constitution than playing politics, but the guys above him are stone-cold hawks and don’t like it when liberal President Jordan Lyman (Fredric March) signs a nuclear disarmament agreement with the Soviets. Reading cables, hearing secondhand conversations, and finding an incriminating crumpled note leads Jiggs to deduce that Scott is planning a military coup against The White House. He takes his suspicion directly to the president and then begins a cat and mouse game of cloak n’ dagger, teaming with the most trusted members of the president's inner circle, including his top aide, Paul Girard (Martin Balsam), a crusty drunken Southern congressman played wonderfully by Edmond O’Brien (he won an Oscar ten years earlier for his performance in The Barefoot Contessa), and finally Jiggs cozies up to a boozy Washington socialite, Eleanor Holbrook (Ava Gardner), who knows all the town’s players and harbors secrets.

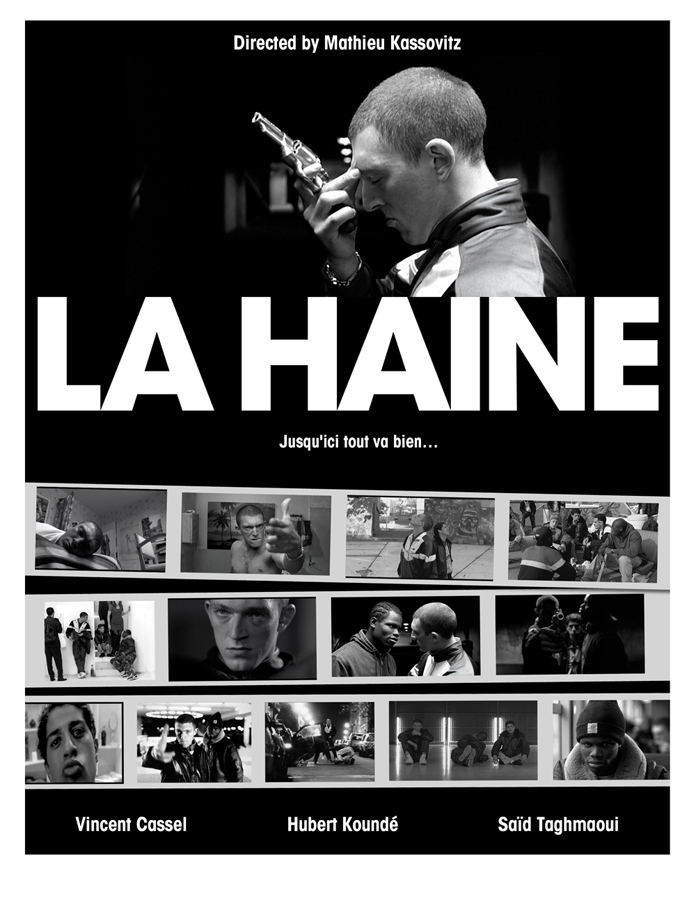

La Haine

“It’s not the fall that kills, but the way you land.”

“It’s not the fall that kills, but the way you land.”

—Hubert’s philosophical metaphor of falling is emotionally applied to survival in the projects in 1995’s La Haine.

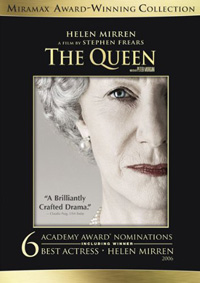

The Queen

Playwright and screenwriter Peter Morgan has become one of the top chroniclers of odd-couple conflicts just below the surface of history's reach during the last couple decades. The Last King of Scotland was about the relationship between Ugandan dictator Idi Amin and his young Scottish doctor. Frost/Nixon chronicled the details of the famous filmed conversations between the broadcaster and the disgraced ex-president. Morgan's television movie, The Deal, directed by Stephen Frears, contrasted the difference between two British politicians, Gordon Brown and Tony Blair. As a follow-up, Morgan, Frears, and actor Michael Sheen, who perfectly captures Blair in looks and spirit, re-teamed with The Queen. This time Blair is a supporting character on screen, though still a vital half of another mismatched odd couple with Queen Elizabeth II, played brilliantly by Helen Mirren. The Queen details how Blair just might have saved the royal family from total irrelevancy after their reluctance to acknowledge Princess Diana after her death.

Playwright and screenwriter Peter Morgan has become one of the top chroniclers of odd-couple conflicts just below the surface of history's reach during the last couple decades. The Last King of Scotland was about the relationship between Ugandan dictator Idi Amin and his young Scottish doctor. Frost/Nixon chronicled the details of the famous filmed conversations between the broadcaster and the disgraced ex-president. Morgan's television movie, The Deal, directed by Stephen Frears, contrasted the difference between two British politicians, Gordon Brown and Tony Blair. As a follow-up, Morgan, Frears, and actor Michael Sheen, who perfectly captures Blair in looks and spirit, re-teamed with The Queen. This time Blair is a supporting character on screen, though still a vital half of another mismatched odd couple with Queen Elizabeth II, played brilliantly by Helen Mirren. The Queen details how Blair just might have saved the royal family from total irrelevancy after their reluctance to acknowledge Princess Diana after her death.

After the humiliating divorce between Prince Charles and Princess Diana, England’s monarchy might need to ask itself some hard questions, but Queen Elizabeth won't have it. When the touchy-feely Tony Blair, England’s answer to Bill Clinton, was elected Prime Minister in 1997 with promises to modernize the country, it sent shivers up the spines of the royal family. A few months after getting elected and an awkward first meeting with the Queen, they are both at the center of a storm when Diana and her playboy boyfriend, Dodi Fayed, are tragically killed in a Paris car accident. The royal family have no idea how to react. The Queen resorts to her WWII “stiff upper lip” posture: say nothing, show no emotion, and just stay out of the public eye. Tradition! Diana was no longer part of the royal family, so it was not her concern. But Blair understood the modern sensibility of public mourning and after dubbing her “the People’s Princess” his numbers skyrocket while the Queen’s coldness sinks her.

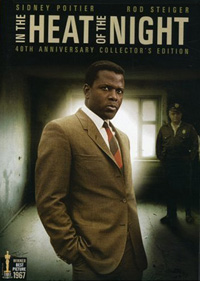

In The Heat Of The Night

The racial politics of In The Heat Of The Night may not be as shocking or edgy today as they were back in the bad old days of 1967. Matter of fact, it may even be a little corny and perhaps the drama can feel obvious, but as a piece of detective pulp it’s solid, and as a showcase for the great Rod Steiger at his scenery-chewing best it’s more than watchable. This was a period full of Southern dramas with some then socially hot elements - Hurry Sundown, ...tick…tick… tick…, The Liberation Of L.B. Jones, The Klansman, even The Chase. While those films are all utterly dated (they would seem a little more brave if they had been produced ten year earlier), In The Heat Of The Night holds up fairly well, because it’s a mystery film first, with a lot of style, and an all-star team behind the camera. It’s also the best of Sidney Poitier’s groundbreaking run of films in the '60s that made him the first black box office superstar.

The racial politics of In The Heat Of The Night may not be as shocking or edgy today as they were back in the bad old days of 1967. Matter of fact, it may even be a little corny and perhaps the drama can feel obvious, but as a piece of detective pulp it’s solid, and as a showcase for the great Rod Steiger at his scenery-chewing best it’s more than watchable. This was a period full of Southern dramas with some then socially hot elements - Hurry Sundown, ...tick…tick… tick…, The Liberation Of L.B. Jones, The Klansman, even The Chase. While those films are all utterly dated (they would seem a little more brave if they had been produced ten year earlier), In The Heat Of The Night holds up fairly well, because it’s a mystery film first, with a lot of style, and an all-star team behind the camera. It’s also the best of Sidney Poitier’s groundbreaking run of films in the '60s that made him the first black box office superstar.

In Sparta, Mississippi patrolman Sam Wood (the great character actor Warren Oates) makes his nightly rounds, after peeping at a topless woman he makes a startling discovery – the murdered body of wealthy Industrialist, Philip Colbert. Newly installed police chief Bill Gillespie (Steiger) sends him to check out the pool hall and bus station for any drifters, and wouldn’t you know it, Wood finds a well-dressed black man with a wallet full of bills waiting for a bus. The cops think they have an open and shut case, until they find out the black man, with a clear alibi, is actually Virgil Tibbs (Poitier), a Philadelphia homicide detective just passing through. The fact that he makes more money than them, is obviously smarter and is black throws these backwoods hicks for a loop. Tibbs wants to leave town but after clearing another wrongly accused guy, he impresses the deceased man’s wife, Leslie Colbert (Lee Grant), and she puts pressure on Gillespie to keep Tibbs on the case. And of course, Tibbs’ super-sleuthing leads to budding respect from the otherwise racist cops.